- ...1

- This section was added August 2023 for the next (third) printing of the 2010 edition, since it contains nothing new since 2010, in principle.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...2

- This section was added August 2023 for the next (third) printing of the 2010 edition, since it contains nothing new since 2010, in principle.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...3

- This section was added August 2023 for the next (third) printing of the 2010 edition, since it contains nothing new since 2010, in principle.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...4

- This section was added August 2023 for the next (third) printing of the 2010 edition, since it contains nothing new since 2010, in principle.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

email1.1

- jos at ccrma

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... performance.2.1

- This distinction

is also important when evaluating real-world musical instruments.

It is better to ask a skilled performer to comment on the quality of

an instrument than a listener. A good musician can make almost any

instrument sound good, while appreciating its defects and working

around them in performance.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

pianos''.2.2

- For example, the Synthogy Ivory (a $349

software product in 2006), ships as 40 Gigabytes on ten DVDs (three

sampled pianos). Every key is sampled, with 4-10 ``velocity

layers'', separate recordings with the soft pedal down, and separate

``release'' recordings, for multiple striking velocities. (Source:

Electronic Musician magazine, October 2006)

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... acoustic2.3

- In the case of audio effects,

``acoustic'' recordings are normally replaced by ``electronic''

recordings. The same applies to the sampling of vintage electronic

instruments, such as the Fender Rhodes electric piano, etc.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

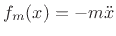

- ... equation2.4

- See

Appendix B for further discussion of Newton's laws of motion.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

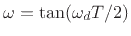

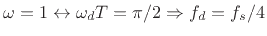

- ...2.5

- Digitizing a system generally means

converting it from continuous-time to discrete-time form. For an

ODE, for example, this typically involves algebraically replacing

the time differential

in the ODE by a practical sampling

interval

in the ODE by a practical sampling

interval  , as will be discussed below and in §7.3.1.

, as will be discussed below and in §7.3.1.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... dashpot2.6

- A

dashpot is the idealized mechanical equivalent of a

resistor in electrical circuit theory. Its compression-velocity

is proportional to applied force, i.e.,

.

Dashpots are often used to model forces due to friction and

are typically valid over a restricted frequency range. Masses and

springs are mechanical equivalents of electrical inductors and

capacitors, respectively. More about these elements will be

discussed below in this chapter and later in this book.

.

Dashpots are often used to model forces due to friction and

are typically valid over a restricted frequency range. Masses and

springs are mechanical equivalents of electrical inductors and

capacitors, respectively. More about these elements will be

discussed below in this chapter and later in this book.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ....2.7

- Transverse displacement

is displacement in a plane orthogonal to the string axis

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... beyond.2.8

- It is interesting to note that in the

development of quantum mechanics in the early 1900s, it was

necessary to replace deterministic Newtonian dynamics with a

probabilistic model. In quantum mechanics, probability

distributions may follow deterministic trajectories as in Newtonian

mechanics (see, for example, Schrödinger's equation), but they are

only probability distributions, so there is no deterministic ``clock

works'' at the smallest physical scales. We are fortunate to be able

to use Newtonian dynamics with such great accuracy. Our difficulty will

be complexity, not randomness. Paradoxically, the typical way to

deal with overwhelming complexity is to model it as random (e.g.,

filtered white noise).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

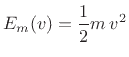

- ....2.9

- As discussed in §1.3.6, only velocity

is

needed for the state variable of a mass, since a mass moving in one

dimension has only one degree of freedom (with energy

is

needed for the state variable of a mass, since a mass moving in one

dimension has only one degree of freedom (with energy  ).

However, since it is physically reasonable to expect both velocity

and position to be needed for the state of a point mass, let's

``play that out'' and see how it goes. This also gives us a simple

vector example to study.

).

However, since it is physically reasonable to expect both velocity

and position to be needed for the state of a point mass, let's

``play that out'' and see how it goes. This also gives us a simple

vector example to study.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... proper2.10

- See

[452, p. 133] regarding the cases

for which a

``long division'' is first performed to obtain an FIR part in

parallel with a strictly proper part.

for which a

``long division'' is first performed to obtain an FIR part in

parallel with a strictly proper part.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... diagonal.2.11

- More precisely,

is diagonal when the

poles are distinct. A repeated pole can result in a block of

is diagonal when the

poles are distinct. A repeated pole can result in a block of

having 1s along its superdiagonal.

having 1s along its superdiagonal.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

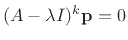

- ... eigenvectors.2.12

- A

generalized eigenvector

of matrix

of matrix  corresponding to

eigenvalue

corresponding to

eigenvalue  having multiplicity

having multiplicity  is a nonzero solution

of

is a nonzero solution

of

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... zero.2.13

- The other law routinely used in

circuit analysis is that the sum of all currents entering a

circuit node (connection of wires) is zero. This kind of

analysis will be revisited in §9.3.1.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... resistance.2.14

- Note that models of damping in

practical physical systems are rarely completely independent of

frequency, as is the ideal dashpot.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...JOSFP2.15

- For a short online introduction to Laplace transforms, see, e.g.,

http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/filters/Laplace_Transform_Analysis.html.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... direction.3.1

- To determine whether a surface is

effectively flat, it may first be smoothed so that variations less

than a wavelength in size are ignored. That is, waves do not ``see''

variations on a scale much less than a wavelength.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...STK4.3.2

- In the code of Fig.2.10, the first executable line

changes the global STK sampling-rate from 44100 Hz (the default) to

that of the input soundfile. If this is not done, there is a hidden

sampling-rate conversion using linear interpolation when the input

file is read, if its sampling rate is different from the global STK

sampling-rate. This default rate conversion could alternatively be

canceled by saying input.setRate(1.0); after the input file

is opened.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

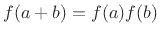

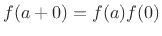

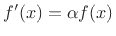

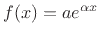

- ....3.3

- It is easy to see that the exponential function

has the property

has the property

. To show that all

differentiable functions with this property are exponentials, one can

look at the definition of the derivative of

. To show that all

differentiable functions with this property are exponentials, one can

look at the definition of the derivative of  with respect to

with respect to

:

:

Since

, we must have

, we must have  . Therefore, the last

limit above converges to some constant

. Therefore, the last

limit above converges to some constant

, and

, and

. In this way, it is shown that

. In this way, it is shown that  satisfies a differential equation whose solution space consists of

exponential functions of the form

satisfies a differential equation whose solution space consists of

exponential functions of the form

, and to obtain

, and to obtain

, we must have

, we must have  .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

dispersion3.4

- Dispersion occurs in a

traveling wave whenever the propagation speed is different at two or

more frequencies.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... equal.3.5

- The signs may differ, however. For

example, imagine twisting a stretched string about a point

along its length in the plane of transverse vibration. In that

case, the transverse-displacement pulses propagating away from the

twist have opposite sign. This opposite-sign effect happens also

for slope waves emanating from a pluck disturbance, as we'll

see in Chapter 6. (A positive pluck corresponds to a

positive slope on its left and a negative slope on its right.)

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... law3.6

- Newton's third law states that ``every

action produces an equal and opposite reaction.'' Therefore, every

``physical'' signal connection must be bidirectional, in

order to model both the applied force and the equal reaction force,

or ``loading effect''. Bidirectional signal connections are

typically called ports. A ``port'' (one physical

connection point) in electrical circuit theory consists of two

variables, typically voltage and current. In acoustics,

corresponding port variables would be pressure and velocity. As

discussed later (e.g., for Wave Digital Filters in Appendix F), a

simple 2x2 matrix linear transformation converts ``force and flow''

port variables, such as these, to ``traveling-wave component'' port

variables.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

waves3.7

- Loading effects can be viewed as the result of

instantaneous return waves. This equivalence is seen clearly, for

example, in Wave Digital Filters (Appendix F).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

neglected.3.8

- This follows years of standard practice in analog

electric circuit design using voltage transfer

interconnections. For ``voltage transfer'' from one circuit-stage

to another with minimized loading effects, output impedances are

made as low as practical, while input impedances are set very high.

For example, in analog synthesizers built during the 1970s, input

impedances were typically around 100 times output impedances (e.g.,

100K and 1K Ohms, respectively in a typical op-amp circuit)

[205].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... as3.9

- Note that

Fig.2.24 is given in direct form 2, so its describing equations are

. To make the figure

correspond exactly to the direct-form-1 difference equation, simply

move

. To make the figure

correspond exactly to the direct-form-1 difference equation, simply

move  from the output arrow to the input arrow. That is, commute

the scaling by

from the output arrow to the input arrow. That is, commute

the scaling by  and the feedback loop so that

and the feedback loop so that  is first.

is first.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... filter|textbf,3.10

- Readers of the main chapters of this book are not

required to know linear algebra, but one does not have to learn much

to follow the discussion in this section. See, for example,

[454, available online] for the basic matrix operations. An

excellent linear algebra text is [332]. See also the lecture

videos by Strang by searching for ``linear algebra'' at

http://ocw.mit.edu/.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ....3.11

- If

is complex, transposition must include

complex conjugation, i.e.,

is complex, transposition must include

complex conjugation, i.e.,

. The

conjugate-transpose

. The

conjugate-transpose

is called the Hermitian

transpose of

is called the Hermitian

transpose of

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

1,3.12

- By definition,

, so that all singular values

of an orthogonal matrix are equal to 1.

, so that all singular values

of an orthogonal matrix are equal to 1.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... line.3.13

- This

structure may be quickly derived by forming a series combination of a

feedback comb filter followed by a feedforward comb filter, and

noticing that the two delay lines contain the same numbers at all

times. Therefore, the two delay lines can be replaced by a single

shared delay line.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...causal|textbf3.14

- A filter is said

to be causal if its impulse response

is zero for

is zero for  .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

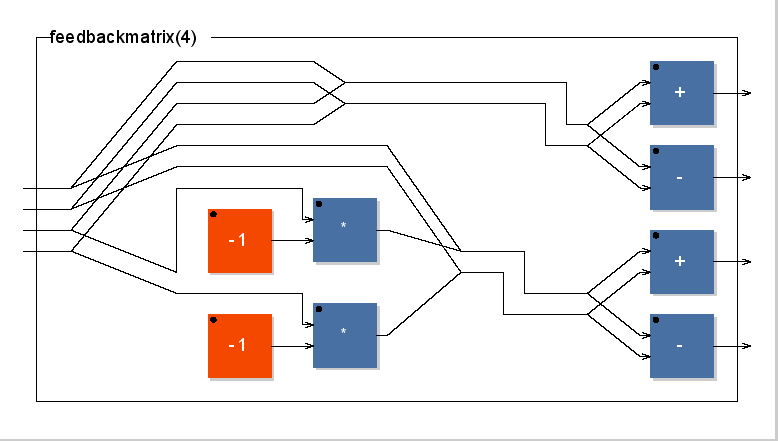

- ...fbffcf.3.15

- Gerzon's starting point was Schroeder's

allpass which differs slightly from Eq.(2.15), having difference

equation [415]

with  required for stability. This structure can be derived

from Eq.(2.15) on page

required for stability. This structure can be derived

from Eq.(2.15) on page ![[*]](../icons/crossref.png) by moving the feedforward path to

the other side of the input summer and deriving the new gain for

by moving the feedforward path to

the other side of the input summer and deriving the new gain for

. Gerzon's idea was to replace the

. Gerzon's idea was to replace the  -sample delay by a

multi-input, multi-output (MIMO) allpass-filter matrix;

Gerzon's ``unitary frequency-response matrices'' correspond to

paraunitary matrix transfer functions

[452, Appendix D].

-sample delay by a

multi-input, multi-output (MIMO) allpass-filter matrix;

Gerzon's ``unitary frequency-response matrices'' correspond to

paraunitary matrix transfer functions

[452, Appendix D].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... matrix|textbf3.16

- A (possibly complex) matrix

is said to be

unitary if

is said to be

unitary if

, where

, where

is the Hermitian transpose of

is the Hermitian transpose of  . A real

unitary matrix is said to be orthogonal, which is the case

most commonly used in practice.

. A real

unitary matrix is said to be orthogonal, which is the case

most commonly used in practice.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... impedance3.17

-

See §7.1 for definitions and discussion regarding

impedance.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... ear,4.1

- One tapped

delay line can also model one source to multiple ears, or vice versa

(Fig.5.6).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... time4.2

- Reverberation time is

typically defined as

,

the time, in seconds, to decay by 60 dB.

,

the time, in seconds, to decay by 60 dB.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... shown4.3

- A simple proof for rectangular rooms can be based on

considering a single spherical wave produced from a point source in

the room. Imagine tesselating all of 3D space with copies of the

original room (minus the source), all in the same orientation. As

the spherical wave expands, it intersects a number of rooms that is

roughly proportional to its radius squared. Since the radius is

proportional to time for an expanding spherical wavefront (

),

the number of rooms containing a wave section grows as

),

the number of rooms containing a wave section grows as  . By

adding all the rooms together (flipping every other one along

. By

adding all the rooms together (flipping every other one along  and

and  ), we obtain the acoustic field in the original reverberant

room at time

), we obtain the acoustic field in the original reverberant

room at time  , for the case of lossless wall reflections of

pressure waves. (This is the dual of the usual image method

for computing the impulse response of a room

[11].) Since each wave-section traverses each

point exactly once in each room image (disregarding reflections,

which are accounted for by different room images), the number of

echoes at any point in the room during the time it takes a plane

wave to traverse the room is very close to the number of wave

sections in the room at the beginning of that time interval.

Incidentally, this construction gives, in the limit as

, for the case of lossless wall reflections of

pressure waves. (This is the dual of the usual image method

for computing the impulse response of a room

[11].) Since each wave-section traverses each

point exactly once in each room image (disregarding reflections,

which are accounted for by different room images), the number of

echoes at any point in the room during the time it takes a plane

wave to traverse the room is very close to the number of wave

sections in the room at the beginning of that time interval.

Incidentally, this construction gives, in the limit as

,

a derivation and vivid visualization of the diffuse

field--the superposition of equal-amplitude traveling

plane-waves arriving from all directions and having uniformally

distributed random arrival phase [352,47].

,

a derivation and vivid visualization of the diffuse

field--the superposition of equal-amplitude traveling

plane-waves arriving from all directions and having uniformally

distributed random arrival phase [352,47].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

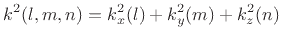

- ... shown4.4

- As described in virtually any acoustics textbook, the resonant modes of a

rectangular room are given by (see, e.g., [352, pp. 284-286])

|

(4.1) |

where

denotes the

denotes the  th harmonic frequency (radian/meter)

of the fundamental standing wave in the

th harmonic frequency (radian/meter)

of the fundamental standing wave in the  direction (

direction ( being the

length of the room along

being the

length of the room along  ), and similarly for the

), and similarly for the  and

and  directions. Thus, the mode frequencies of a room can be enumerated on

a uniform 3D Cartesian grid indexed by

directions. Thus, the mode frequencies of a room can be enumerated on

a uniform 3D Cartesian grid indexed by  . The grid spacings

along

. The grid spacings

along  ,

,  , and

, and  are taken to be

are taken to be  ,

,  , and

, and

, respectively. From Eq.(3.1), the spatial frequency

, respectively. From Eq.(3.1), the spatial frequency

of mode

of mode  is given by the distance from the origin

of the grid to the point indexed by

is given by the distance from the origin

of the grid to the point indexed by  . Therefore, the number of room

modes having spatial frequency between

. Therefore, the number of room

modes having spatial frequency between  and

and  is equal to

the number of grid points lying in the spherical annulus between

radius

is equal to

the number of grid points lying in the spherical annulus between

radius  and

and  . Since the grid is uniform, this number

grows as

. Since the grid is uniform, this number

grows as  .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

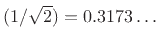

- ...4.5

- One definition of when late

reverberation begins is when it begins to look Gaussian, since

a random sum of plane waves uniformly distributed over all angles of

arrival yields a Gaussian distributed pressure field. (The fact that

late reverberation in a rectangular room always approaches the diffuse field--a

superposition of plane waves traveling in all directions can be seen

from the ``image-method dual'' argument in §3.2.1.) One way to

test for Gaussianness is to form a histogram of impulse

response sample values over a finite window (say 10ms, or roughly 500

samples), and compare the normalized histogram

to a standard

Gaussian bell curve

to a standard

Gaussian bell curve  computed using the measured sample

variance. A threshold can be placed on

computed using the measured sample

variance. A threshold can be placed on

, or some

number of higher order sample moments can be compared. A simpler test

is to determine when roughly 30% of the samples in a frame have

magnitude larger than one standard deviation (

, or some

number of higher order sample moments can be compared. A simpler test

is to determine when roughly 30% of the samples in a frame have

magnitude larger than one standard deviation (

)

[3],

since the probability of this occurring in truly Gaussian sequences is

)

[3],

since the probability of this occurring in truly Gaussian sequences is

erf

erf , where

erf

, where

erf denotes the ``error function'' (integral from

denotes the ``error function'' (integral from  to

to  of the

Gaussian probability density function with normalized variance

of the

Gaussian probability density function with normalized variance

). For a zero-mean signal

). For a zero-mean signal  , the sample standard

deviation

, the sample standard

deviation  is given by the root-mean-square (RMS level).

Another

desired property of ``late reverb'' is that the remaining energy in

the impulse response (Schroeder's Energy Decay Curve (EDC)

[416]), has begun what appears to be an

exponential decay. This can be ascertained by fitting an exponential

to the EDC using, e.g., Prony's method.

is given by the root-mean-square (RMS level).

Another

desired property of ``late reverb'' is that the remaining energy in

the impulse response (Schroeder's Energy Decay Curve (EDC)

[416]), has begun what appears to be an

exponential decay. This can be ascertained by fitting an exponential

to the EDC using, e.g., Prony's method.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... (TDL).4.6

- This idea was apparently first suggested by

Schroeder in 1970 [418] and evidently first implemented

by Moorer [317].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...MoorerReverb79.4.7

- In computer music, an old trick

for making a synthesized tone sound reverberated is to randomly modulate

its amplitude envelope, and to append a low-level exponentially decaying

tail to the amplitude envelope (also modulated). This can produce a very

convincing illusion.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

examples.4.8

- https://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/wav/FM-BrassCanon2.wav

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ....4.9

- As

an alternative to the output delay values shown in Fig.3.7,

the values

![$ [0.013, 0.011, 0.019, 0.017]f_s$](img722.png) have been used.

have been used.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... alone.4.10

- There is a Freeverb

pd ``external'' in both the pd-extended and

faust-pd packages, and it appears in the muse

sequencer, kdemultimedia, clm, and faust

language packages, all included with Planet CCRMA. Other versions may

be found by a Web search for ``Freeverb source'', but I have not found

any version that isn't essentially the same June 2000 version by Jezar

at Dreampoint.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

(LBCF4.11

- ``Lowpass-Back-Comb-Filter''--to keep all the

comb-filter acronyms down to four characters: FFCF, FBCF, LBCF.

Author's prerogative!

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...math.lib4.12

- Details about

Faust may be found at

http://faust.grame.fr/.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... diagonal.4.13

- This is easy to

show by performing an expansion by minors to calculate

, always choosing to expand along the top row (for lower

triangular) or first column (for upper triangular).

, always choosing to expand along the top row (for lower

triangular) or first column (for upper triangular).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

repeats.4.14

- Fritz Menzer, in ``Choosing Optimal Delays for Feedback Delay Networks'',

http://pub.dega-akustik.de/DAGA_2014/data/articles/000025.pdf, found

that ``using mutually prime delays [in FDNs] avoids only a negligible

subset of echo superpositions'', and proposed free optimization of the

delay lengths to achieve desired qualities.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...4.15

- This substitution was first applied

to complete reverberators by Jot [217,218]. The

idea is closely related to the approximate pole analysis in

[317, p. 17], [432, pp. 170-172],

and [208], and somewhat also to the allpass conformal

maps used in [318,461].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...FDNJot).4.16

- Note that, as

developed here, the delay-line filters

should be located

either before or after its associated delay line, while

Fig.3.10 associates it with the feedback matrix. The

difference is typically not audible.

should be located

either before or after its associated delay line, while

Fig.3.10 associates it with the feedback matrix. The

difference is typically not audible.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... dc.4.17

- In a Faust

implementation, this form was found to be more numerically sensitive

than that of the previous section when changing the

s in

real time (see §3.7.9).

s in

real time (see §3.7.9).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... FOSS4.18

- FOSS

Free Open Source Software

Free Open Source Software

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...zita-rev1,4.19

- http://kokkinizita.linuxaudio.org/linuxaudio/zita-rev1-doc/quickguide.html

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...JOSFP,4.20

- https://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/filters/Low_High_Shelving_Filters.html

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

respectively.4.21

- This section describes the Faust version

zita_rev1, which may not be exactly the same as the

C++ version zita-rev1, although each control parameter

range is the same, and the filter-orders are the same, so at least

near-equivalance is expected.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...Kendall84.4.22

- Of course, correct angles-of-arrival

for early reflections are more straightforward to implement using an

array of loudspeakers enclosing the listener.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...5.1

- A causal IIR filter can be used for random-access table

lookup by simply starting the filter at a point sufficiently far

away in the table and ``running it'' until it reaches steady-state

at the desired interpolation point. While this requires at least as

many multiply-adds as an FIR filter spanning the same duration, the

number of IIR filter coefficients can be much less than the number

of FIR filter coefficients required. IIR interpolators are therefore

possibly interesting for certain memory-starved VLSI applications.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... samples.5.2

- Classically, an interpolation

of discrete data points

of discrete data points  always required

always required

;

that is, the interpolating function must always pass through the given

data points. More recently, however, particularly in the field of

computer graphics, interpolation schemes such as Bezier splines

have been defined which do not always pass through the known points.

;

that is, the interpolating function must always pass through the given

data points. More recently, however, particularly in the field of

computer graphics, interpolation schemes such as Bezier splines

have been defined which do not always pass through the known points.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... matlab:5.3

- Say ``help;'' within maxima

and/or ``man maxima'' in a shell to get started. Emacs users

should say ``M-x maxima''.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...5.4

- To see this, consider that a unit-amplitude sinusoid at half

the sampling rate

is either

is either  or

or  . Therefore,

the frequency response

. Therefore,

the frequency response  of every real filter at

of every real filter at  is

a real number

is

a real number

that is either positive or negative (or

zero). When

that is either positive or negative (or

zero). When  , the filter's phase delay must be an even integer

number of samples. When

, the filter's phase delay must be an even integer

number of samples. When  , the filter delay is constrained to be

some odd number of samples. Taken together, the possible delays at

, the filter delay is constrained to be

some odd number of samples. Taken together, the possible delays at

for real filters are the integers. The particular integer is

obtained by finding the limit as

for real filters are the integers. The particular integer is

obtained by finding the limit as

. The case

. The case  can be

associated with a non-integer limit, as suggested by the line for

can be

associated with a non-integer limit, as suggested by the line for

samples delay in Fig.4.18 above, and as easily

shown analytically for order 1 (simple linear interpolation with

coefficients

samples delay in Fig.4.18 above, and as easily

shown analytically for order 1 (simple linear interpolation with

coefficients  , corresponding to a desired delay of

, corresponding to a desired delay of  samples) [452].

samples) [452].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...VesaT.5.5

- http://www.acoustics.hut.fi/~vpv/publications/vesan_vaitos/ch3_pt2_lagrange.pdf

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... rule,5.6

- Evaluation of a polynomial

by Horner's rule can be expressed as

by Horner's rule can be expressed as

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ....5.7

- Of course, all derivatives of

must

be calculated from the underlying continuous signal

must

be calculated from the underlying continuous signal  represented by the samples

represented by the samples  and then evaluated at

and then evaluated at  .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...JOSFP.5.8

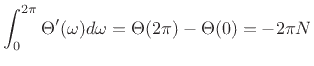

- To see this, note that the integral of the

group delay around the unit circle is simply minus the winding

number of the phase response (the number of zeros minus the number of

poles inside the unit circle):

By the graphical method for phase response calculation [452, Chapter

8], each zero contributes  radians to

radians to

, and each pole contributes

, and each pole contributes  radians. Thus,

the average group delay around the unit circle is

radians. Thus,

the average group delay around the unit circle is

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

processing.5.9

- The material in this section was adapted from

https://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/resample/,

which is an updated online version of [464].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... kHz.5.10

- We arbitrarily define the

% guard band as a

percentage of half the sampling rate actually used, not as

% guard band as a

percentage of half the sampling rate actually used, not as  % of the

desired

% of the

desired  kHz bandwidth which would call for a

kHz bandwidth which would call for a  kHz sampling rate.

kHz sampling rate.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...Bartlett70,SmithAllpassFlanger,Bode84,Anderton85,Dattorro97,Keen99.6.1

- Flanging was apparently invented independently several

times. According to http://www.geofex.com/Article_Folders/phasers/phase.html, the

flanging technique was discovered by Phil Spectre in the 1950s in the

context of trying to ``thicken'' a vocal track by summing two copies

of a track variably delayed in this way. His first use of flanging as

an effect is said to be in his song ``The Big Hurt''.

According to historian Mark Lewisohn [288], as summarized

at http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Flanging

(accessed March 28, 2010), the

term ``flanging'' was coined by John Lennon of the Beatles to describe

what EMI engineer Ken Townsend called ``Artificial Double Tracking''

(ADT). ADT was said to be developed by Townsend in response to John

Lennon's request to try to eliminate the work of recording vocal

tracks twice in order to ``double'' them. George Martin has said to

have explained the effect as follows: ``Now listen, it's very

simple. We take the original image and we split it through a

double-bifurcated sploshing flange with double negative feedback.''

[288]. This suggests that negative regenerative feedback

was used in the original stereo flanging technique

(§2.6.2). The first Beatles track using flanging is

said to have been ``Tomorrow Never Knows'' on the Revolver album

(recorded April 6, 1966). Perhaps the most obvious early example of

flanging was in the popular song ``Itchykoo Park'' by The Small Faces

(1967); this instance is said to have originated with engineer George

Chkiantz at Olympic Studios in London. The song featured a foreground

drum-roll on a snare with strong flanging throughout, and the vocals

were flanged as well.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... sound.6.2

- For sound

examples, see

http://www.harmony-central.com/Effects/Articles/Flanging/.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...notches6.3

- The term notch here refers to the

elimination of sound energy at a single frequency or over a narrow

frequency interval. Another term for this is ``null''.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...Bartlett70,6.4

- According to

http://www.eventide.com/About/History.aspx,

a dual 200 ms delay-line for simulating flanging was called the

Instant Phaser. This was the first commercial product circa

1970 made by Eventide Corp. (better known as makers of the

Harmonizer).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... notches.6.5

- The

author discovered this first-hand by looking at the circuit for the

MXR phase shifter in 1975.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...SmithEtAlDAFx02.6.6

- https://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/doppler/

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...eq:dopplershift).6.7

- If the tape travels in a loop,

then Fig.5.4 provides a model for the Echoplex (Maestro,

1960), which consists of a tape loop with a fixed write-head and

movable read-head.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... first6.8

- The ``first'' write-pointer is defined as the

one writing farthest ahead in time; it must overwrite memory, instead

of summing into it, when a circular buffer is being used, as is

typical.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... Leslie,6.9

- http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Leslie_speaker

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... accurate.6.10

- See also

the Hammond Leslie FAQ at

http://www.theatreorgans.com/hammond/faq/files/hammond-faq.pdf

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...SmithEtAlDAFx02.6.11

- https://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/doppler/

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...dAlembert7.1

- See §A.1 for more about the

history of the wave equation and its traveling-wave solution.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

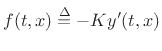

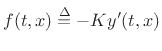

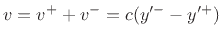

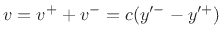

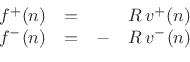

- ... derivation)7.2

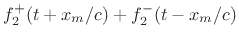

- Note that

and

and  , as

defined, are traveling-wave components of the force acting to

the right on the string. That is, their sum

, as

defined, are traveling-wave components of the force acting to

the right on the string. That is, their sum

is

physically the force that the string-segment to the left of

position

is

physically the force that the string-segment to the left of

position  applies (in the upward direction) to the string-segment

to the right of point

applies (in the upward direction) to the string-segment

to the right of point  . In other words,

. In other words,  denotes

the vertical force applied by the left segment to the right segment at

time

denotes

the vertical force applied by the left segment to the right segment at

time  and position

and position  ; thus, it ``acts to the right'', even though

its traveling-wave components,

; thus, it ``acts to the right'', even though

its traveling-wave components,  and

and  , travel to the left and

right, respectively, at speed

, travel to the left and

right, respectively, at speed  . The net physical force acting to

the right at each point is exactly canceled by an equal and opposite

force acting to the left at each point

. The net physical force acting to

the right at each point is exactly canceled by an equal and opposite

force acting to the left at each point  . See §C.7.2

for a detailed derivation.

. See §C.7.2

for a detailed derivation.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... inversion:7.3

- All wave phenomena involve two physical state

variables--one force-like and the other velocity-like. When one of

these variables reflects from a termination with a sign inversion, the

other reflects with no sign inversion, and vice versa. In acoustic

systems, the force-like variable is pressure, and the velocity-like

variable is either particle velocity (in open air) or volume velocity

(in acoustic tubes), as described in §6.2 above. In

electromagnetic systems, the state variables are electric and magnetic

field strengths or voltage and current. In a mass-spring oscillator,

we may choose the velocity and acceleration of the mass as the

coordinates of our state space, or position and velocity. For

transverse waves on vibrating strings, it is usually preferable to use

force and velocity waves as described above.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...fMovingTermb,7.4

- This

diagram can be seen animated along with

Figure 6.4 at

http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/swgt/movet.html .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... bound.7.5

- Our model becomes invalid as the slope becomes

large. In particular, the string tension

obviously increases as the

string length increases. Here we assume

obviously increases as the

string length increases. Here we assume  is constant.

is constant.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...,7.6

- In somewhat more detail,

so that

, and

, and

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...fsstring7.7

- We should use the notation

for

this loop-filter, since it depends on the string length

for

this loop-filter, since it depends on the string length  (in

samples). The dependence of

(in

samples). The dependence of

on

on  is suppressed for

simplicity of notation.

is suppressed for

simplicity of notation.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...JOSFP.7.8

- http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/filters/Allpass_Filters.html

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...OppenheimAndSchafer,JOSFP.7.9

- http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/filters/Transposed_Direct_Forms.html

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...JOSFP,7.10

- http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/filters/Filters_Preserving_Phase.html

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...invfreqz7.11

- In

Matlab, the Signal Processing Tool Box is required, and in Octave, the

octave-signal MacPort package is needed. The Linux

octave package already includes this (at least on Fedora 13).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...KlapuriMohonk05,KlapuriSAP03,Klapuri01.7.12

- Klapuri's publication home page:

http://www.cs.tut.fi/~klap/iiro/

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

time-slices:7.13

- Note that this derivation also holds if the

power `2' is replaced by an arbitrary

, thereby supporting a

generalization from the EDR to what might be called the ``LPDR'' using

a kind of

, thereby supporting a

generalization from the EDR to what might be called the ``LPDR'' using

a kind of

norm on the remaining decay, where the EDR is

regarded as the

norm on the remaining decay, where the EDR is

regarded as the

case.

case.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ....7.14

- The delay-line length

is only the ``quasi-period''

in samples when the phase delay associated with

is only the ``quasi-period''

in samples when the phase delay associated with  can be

neglected.

can be

neglected.  is never a true ``period'' because the synthesized

signal is decaying from one block to the next.

is never a true ``period'' because the synthesized

signal is decaying from one block to the next.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

instrument.7.15

- Electric guitars with magnetic pickups have

nearly rigid terminations, but even then, coupling phenomena are

clearly observed, especially above the sixth partial or so.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... be7.16

- http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/filters/Finding_Eigenvalues_Practice.html

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

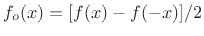

- ... parts.7.17

- It is not necessary to

perform a Taylor series expansion to separate out the even and odd

parts of a function. Instead, the even part of

can be computed

as

can be computed

as

![$ f_e(x) = [f(x)+f(-x)]/2$](img1526.png) and the odd part as

and the odd part as

![$ f_o(x) =

[f(x)-f(-x)]/2$](img1527.png) . It is easily checked that

. It is easily checked that  is even,

is even,  is

odd, and

is

odd, and  .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

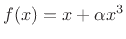

- ... mapping.7.18

- Note that

memoryless nonlinearities used for distortion simulation are typically

odd functions of instantaneous amplitude, such as

. (A good practical choice is given in

Eq.(6.19).) However, in guitar-amplifier distortion

simulation, even-order terms are considered quite important

[398].

. (A good practical choice is given in

Eq.(6.19).) However, in guitar-amplifier distortion

simulation, even-order terms are considered quite important

[398].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...7.19

- The convolution theorem for Fourier transforms states that

convolution in the time domain corresponds to pointwise multiplication

in the frequency domain [452]. The dual of the convolution

theorem states just the opposite: Pointwise multiplication in the time

domain corresponds to convolution in the frequency domain. Thus, if

the spectrum of

is

is  , then the spectrum of

, then the spectrum of  is

is

, where ``

, where `` '' denotes the convolution

operation.

'' denotes the convolution

operation.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... spectra.7.20

- The

basilar membrane of the ear (which is rolled up inside the

snail-shaped cochlea of the ear) effectively performs a real-time

Fourier analysis which is ``felt'' by nerve cells leading to the

brain.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... transform|textbf,8.1

- For a short online introduction to Laplace transforms, see, e.g.,

http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/filters/Laplace_Transform_Analysis.html.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... relation:8.2

- Of course, here we should call it the ``force

divider'' relation.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... mass.''8.3

- We say that the driving point of every mechanical

system must ``looks like a mass'' at sufficiently high frequency

because every mechanical system has at least some mass, and the

driving-point impedance of a mass goes to infinity with frequency.

However, in a completely detailed model, the contact force between

objects should really be the Coulombe force, which ``looks like

a spring''. In other words, mechanical interactions are ultimately

electromagnetic interactions, and it is theoretically possible for a

driving force on an atom to be so small and fast that it can vibrate

the outermost electron orbital without moving the nucleus appreciably,

thus ``looking like a spring'' in the high-frequency limit. We will

not be concerned with atomic-scale models in this book, and will

persist in treating masses and springs in idealized form.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...JOSFP.8.4

- Available online at

http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/filters/Graphical_Amplitude_Response.html

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

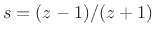

- ....8.5

- To avoid the introduction of

half a sample of delay by the approximation, the first-order finite

difference may be defined instead as

![$ x[(n+1)T]-x[(n-1)T]/(2T)$](img1645.png) .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...JOSFP).8.6

- In

continuous time, the order is incremented once for each

independently moving mass or spring. In discrete time, the order is

increased by one when a sample of delay is added to the system

state, and the number of multiplies needed to implement a digital

simulation is bounded by twice the order plus one.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...JOSFP,8.7

- http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/filters/State_Space_Filters.html

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...blt).8.8

- Normally one or more output signals

are defined as linear

combinations of the state vector

are defined as linear

combinations of the state vector

, viz.,

, viz.,

. However, we can define the state itself as the output for

now, and form any desired linear combinations separately.

. However, we can define the state itself as the output for

now, and form any desired linear combinations separately.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...FranklinEtAl98.9.1

- Estimating transfer functions based on

input-output measurements is called ``system identification''

[290,432]--used in advanced automatic control

applications.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ....9.2

- For

convenience, we typically define the discrete-time counterpart of a

continuous-time function as though the sampling interval were

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

response.9.3

- Frequency-domain aliasing is discussed

in [454].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...JOSFP:9.4

- http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/filters/Partial_Fraction_Expansion.html

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...JOSFP).9.5

- The strictly proper constraint is

natural in practice because the frequency responses of typical

real-world systems generally roll off at least -6 dB per octave.

Notice that Eq.(8.1) becomes

as

as

, which

is a

, which

is a  dB/octave roll off. Setting

dB/octave roll off. Setting  and

and

yields a

yields a  dB/octave roll-off, and so on. However, this depends

on the physical units chosen for the input and output signals of the

system. For example, consider an ideal nonzero mass driven by a

force; while the resulting velocity and displacement go to zero as

frequency goes to infinity (for any finite applied force), the

acceleration does not roll off, being proportional to applied force by

Newton's 2nd law.

dB/octave roll-off, and so on. However, this depends

on the physical units chosen for the input and output signals of the

system. For example, consider an ideal nonzero mass driven by a

force; while the resulting velocity and displacement go to zero as

frequency goes to infinity (for any finite applied force), the

acceleration does not roll off, being proportional to applied force by

Newton's 2nd law.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... modes.9.6

- Modal synthesis

could well be renamed ``Bernoulli synthesis,'' as Daniel Bernoulli

was quite alone in advocating the concept of seeing general

vibration as a superposition of ``simple'' sinusoidal

vibrations. This view was resisted by Euler and d'Alembert at the

time [103].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...JOSFP9.7

- http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/filters/Modal_Representation.html

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... response,9.8

- A

``causal frequency response''

is the Fourier transform of

a causal impulse response

is the Fourier transform of

a causal impulse response  (i.e.,

(i.e.,  for all

for all  ).

Extensions to finitely noncausal spectra are straightforward:

Time-shift the desired impulse response to make it causal, perform

the filter design, then reverse-time-shift the filter numerator if

needed.

).

Extensions to finitely noncausal spectra are straightforward:

Time-shift the desired impulse response to make it causal, perform

the filter design, then reverse-time-shift the filter numerator if

needed.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...9.9

- A stability margin may be specified, for example, by

requiring all poles

to satisfy

to satisfy

, where

, where

determines the stability margin. In particular, with

this specification on the poles, the impulse response

determines the stability margin. In particular, with

this specification on the poles, the impulse response  must

decay asymptotically at least as fast as

must