- ...

email1.1

- jos at ccrma

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... FFT2.1

- ``Fast Fourier

Transform'' -- fast algorithms for implementing the Discrete Fourier

Transform (DFT) [264].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

(DTFT).3.1

- In practical situations we can only deal with

finite-duration signals, so really we always use the Discrete Fourier

Transform (DFT) [264]. Moreover, the DFT is typically

implemented using the split-radix Cooley-Tukey Fast Fourier Transform

(FFT), which requires the DFT length to be a power of 2. Thus, in

practice, we use an FFT, while for theoretical studies, the DTFT is

preferred.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...MDFT.3.2

- http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/mdft/Fourier_Theorems_DFT.html

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... variable,3.3

- The symbol ``

'' means ``is

defined as'' or ``equals by definition.'' In conformity with typical

signal-processing literature, most of this chapter

uses normalized frequency, i.e., the sampling rate equals

'' means ``is

defined as'' or ``equals by definition.'' In conformity with typical

signal-processing literature, most of this chapter

uses normalized frequency, i.e., the sampling rate equals

sample per second.

sample per second.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...MDFT.3.4

- http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/mdft/Fourier_Theorems.html

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

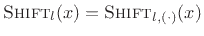

- ... states3.5

- Our

notational convention is that the first subscripts of an operator such

as

are its parameters, as in

are its parameters, as in

, and the last

subscript selects a particular sample of output, as in

, and the last

subscript selects a particular sample of output, as in

. If the last subscript is omitted, it ``returns''

an entire signal. Thus,

. If the last subscript is omitted, it ``returns''

an entire signal. Thus,

is a scalar while

is a scalar while

is an entire signal defined over the integers. We

also may use

is an entire signal defined over the integers. We

also may use  to denote all values of some index, e.g.,

to denote all values of some index, e.g.,

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... cases.3.6

- For

definitions of the DFT, DTFT, FT, and FS, see Table 2.1

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...3.7

- If the sampling density is not sufficiently high, there will

be aliasing (wrap-around) in the time domain. DTFT sampling

in the frequency domain is an exact Fourier dual of ordinary

sampling in the time domain.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...MDFT:3.8

- http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/mdft/Zero_Padding.html

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

practice.3.9

- Nevertheless, as discussed in [266],

a perceptually exact

band-limited interpolation can be implemented at a reasonable cost in

the time domain, provided some amount of

oversampling is used. Oversampling in the time domain provides

a guard band in the frequency domain, which enables the

interpolation kernel to meet perceptually ideal specifications at a

much smaller length [270].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...spectsamps.3.10

- In particular, zero-padding does not increase the resolution

of an FFT. This is a surprisingly common point of misunderstanding

(or sometimes just mislabeling).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... work.3.11

- One could say the

Blackman window is well matched to ``analog synthesizer quality''

levels, where a 60 dB signal-to-noise ratio is common.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

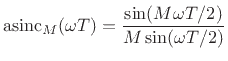

function|textbf:4.1

- Note that writing

to denote the aliased

sinc function is not standard practice in signal processing--consider

it proposed notation.

to denote the aliased

sinc function is not standard practice in signal processing--consider

it proposed notation.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

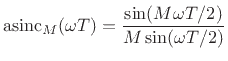

- ....4.2

- In more detail, start with the ``physical'' definition of

:

:

|

(4.9) |

Now replace  by

by  in the numerator. Take the limit as

in the numerator. Take the limit as  goes to zero, with

goes to zero, with  remaining fixed, so that

remaining fixed, so that  goes to

infinity (maintaining the relation

goes to

infinity (maintaining the relation

). When

). When  gets very

small, the denominator becomes

gets very

small, the denominator becomes

|

(4.10) |

which completes the proof.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... crossings.4.3

is the

radian-frequency sampling interval for a length

is the

radian-frequency sampling interval for a length  DFT. Using

DFT. Using

to denote the sampling interval along

to denote the sampling interval along  is analogous

to using

is analogous

to using  to denote the sampling interval along time

to denote the sampling interval along time  -- hence

the choice of symbol

-- hence

the choice of symbol  .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...Harris78.4.4

- The Hamming window can also be derived as a

special case of windows having a maximized main-lobe peak

over

all windows of the same energy and prescribed first zero-crossings

about the main lobe

[202, p. 239,403].

over

all windows of the same energy and prescribed first zero-crossings

about the main lobe

[202, p. 239,403].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...Harris78.4.5

- Note that the

dB figure is

for large window-length

dB figure is

for large window-length  . For small window lengths, the side-lobe

levels increase. This phenomenon can be understood in terms of

aliasing of the side-lobes of the continuous Hamming window which must

be sampled to obtain a discrete-time window.

. For small window lengths, the side-lobe

levels increase. This phenomenon can be understood in terms of

aliasing of the side-lobes of the continuous Hamming window which must

be sampled to obtain a discrete-time window.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... dB,4.6

- For larger

window-length

, more than

, more than  dB side-lobe suppression can be

achieved, such as the

dB side-lobe suppression can be

achieved, such as the  value cited in [101].

value cited in [101].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... Hann4.7

- The precise side-lobe level is dependent on window

length

, but

, but  to

to  dB is typical for the Hamming

window.

dB is typical for the Hamming

window.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...Papoulis.4.8

- The proof that

(3.36) is maximized appears on p. 210 of [202].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ....4.9

- From a

linear algebra point of view, consider the sinc kernel as

corresponding to a Toeplitz Hermitian matrix. It is well known

that Hermitian matrices have real eigenvalues and orthogonal

eigenvectors. Also, multiplication by a Toeplitz matrix corresponds

to convolution (in this case, a non-causal convolution.)

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

Box4.10

- For Octave, the original version by Eric Breitenberger is

still available on the Web, as of this writing, at

http://pangea.stanford.edu/Oceans/GES290/Breitenberger-SSAMatlab/mtm/.

Note, however, that the calling arguments after the first two are

differently defined. A simple version written by the author appears

in §F.1.2.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... by4.11

- For small

and/or

and/or

, the closed-form transform diverges from the DTFT of the

discrete-time Kaiser window due to aliasing.

, the closed-form transform diverges from the DTFT of the

discrete-time Kaiser window due to aliasing.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

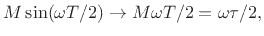

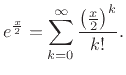

- ... kind:4.12

- The Maclaurin series for

can be obtained as

the term-by-term square of that for

can be obtained as

the term-by-term square of that for  , since

, since

|

(4.41) |

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... radians-per-second).4.13

- In

[101],

is described as half of

the time-bandwidth product, which in turn is not defined. Factors of

2 often come and go because, e.g., the frequency band

is described as half of

the time-bandwidth product, which in turn is not defined. Factors of

2 often come and go because, e.g., the frequency band

![$ [-\omega_c,\omega_c]$](img468.png) is often considered a bandwidth of

is often considered a bandwidth of  (neglecting negative frequencies).

(neglecting negative frequencies).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ....4.14

- The causal version may be

computed as the inverse DFT of

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

itself.4.15

- The not-so-smooth function

also

transforms to itself

[150, p. 47]. Also, a periodic impulse train transforms

to an impulse train with reciprocal spacing of the impulses

(see §B.14). Finally, as discussed at

http://www.dsprelated.com/showarticle/45.php,

if

also

transforms to itself

[150, p. 47]. Also, a periodic impulse train transforms

to an impulse train with reciprocal spacing of the impulses

(see §B.14). Finally, as discussed at

http://www.dsprelated.com/showarticle/45.php,

if  is real and even, then

is real and even, then

is its own transform

under the normalized Fourier transform. (The normalized Fourier

transform is the usual Fourier transform divided by

is its own transform

under the normalized Fourier transform. (The normalized Fourier

transform is the usual Fourier transform divided by

,

which results in the inverse transform having the same scale factor.)

That is,

,

which results in the inverse transform having the same scale factor.)

That is,

.

We used the fact that if

.

We used the fact that if  is real and even, then so is

is real and even, then so is

. (This is shown for the DTFT case in §2.3.3,

and the proof is analogous in the continuous-time case.) Note that

for

. (This is shown for the DTFT case in §2.3.3,

and the proof is analogous in the continuous-time case.) Note that

for  to be smooth (differentiable of all orders), it cannot be

bandlimited in either time or frequency.

to be smooth (differentiable of all orders), it cannot be

bandlimited in either time or frequency.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... design.4.16

- A spectrum-analysis window

may be regarded as an FIR lowpass filter having an extremely narrow

pass-band.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

CPUs5.1

- In recent years, Graphics Processing Units (GPUs) have

been used increasingly for high-performance general-purpose digital

signal processing [242]. For example, the NVIDIA

CUDA development environment allows harnessing of many parallel

threads of execution in a GPU (typically on a graphics card or

chip-set in a personal computer) from a C program using GPU-related

library extensions. Due to the massive parallelism available in a GPU,

FFT convolution becomes competitive with time-domain convolution only

at much longer lengths (in the thousands) [242]. In a

CPU (one processor), FFT methods typically win out for convolution

lengths greater than 100 or so (see §8.1.4 for some

details).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

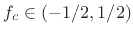

- ... frequencies.5.2

- In this book, unless

specified otherwise, all frequencies are normalized by the

sampling rate. Thus,

is physically ``cycles per

sample.''

is physically ``cycles per

sample.''

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...optfirlp.5.3

- In fact,

optimal window design is a special case of optimal FIR lowpass design

in which the desired pass-band width is nearly zero, as we will see.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

audible.5.4

- A 0.1 dB pass-band ripple results in a normally

inaudible amplitude error, while a -60 dB stop-band ripple can be

quite audible if the pass-band is relatively quiet and high signal

energy appears in the stop-band.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

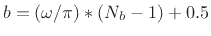

- ... frequency)5.5

- It is a

common matlab convention to specify normalized frequencies between

0 and 1 such that 1 corresponds to half the sampling rate,

instead of the sampling rate. Thus, one-fourth the sampling rate

(

) is specified as

) is specified as  in matlab. In this

book, outside of Matlab function arguments, normalized frequency

in matlab. In this

book, outside of Matlab function arguments, normalized frequency

is always the sampling rate.

is always the sampling rate.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ....5.6

- As a result of the implicit equal weighting, the

stop-band ripple at

dB means that the pass-band ripple

is below 0.007 dB, which is overkill for typical audio applications.

This pass-band ripple can be enlarged in exchange for improved

stop-band ripple or a narrower transition band or both. This is done

by specifying a larger weighting on the stop-band ripple--see the

help page for firpm for details.

dB means that the pass-band ripple

is below 0.007 dB, which is overkill for typical audio applications.

This pass-band ripple can be enlarged in exchange for improved

stop-band ripple or a narrower transition band or both. This is done

by specifying a larger weighting on the stop-band ripple--see the

help page for firpm for details.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... design5.7

- Recall that window

design can be formulated as FIR lowpass-filter design with a

zero-with (or nearly zero-width) pass-band.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... ``tight''.5.8

- Our choice came from

as used in [228].

as used in [228].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...RabinerAndGold.5.9

- Show this as an exercise. [Hint: Recall

the stretch theorem (§2.3.11).]

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... response.5.10

- It is effective in

practice to try doubling the FFT size to see if it appreciably

changes the designed filter--it should not.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... consequences.5.11

- However, consider an

FM signal in which a sinusoid is sweeping back and forth in the

pass-band. In that case, the pass-band-ripple generates AM

sidebands, so a spec more like that in the stop-band may be called

for. Here, we allow the pass-band ripple to be 10 times the

stop-band ripple, which is a reasonable compromise.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... gains.5.12

- While cubic splines are maximally

smooth in a precise physical sense, they are not band-limited, so

one can do better by using band-limited interpolation of the

desired frequency-response points. (In this situation,

``band-limited'' equals ``time-limited,'' which is exactly what we

are going for in an FIR filter design.)

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

Octave).5.13

- At the time of this writing, remez is a C-compiled

extension (.oct file) in the octave-signal package

for Linux (Red Hat Fedora 16), but not in the package of the same

name under MacPorts for Mac OS X. To create a new C-compiled

extension, the original Fortran listing from

[66,224], e.g.,

http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/sasp/remez.f4

can be converted to C using f2c from

http://www.netlib.org/f2c/.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ....5.14

- Equivalently, (4.38)

can be minimized by one step of Newton's method.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... (Hz).6.1

- Long ago, the term for Hz was cycles per

second (cps).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ....6.2

- More

generally, an analytic signal is obtained from a real signal by

filtering out its negative-frequency components. In other terms, the

imaginary part of the analytic signal may be obtained as the

Hilbert transform of the real part (see

§4.6).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

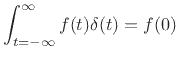

property6.3

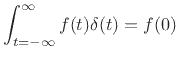

- The sifting property of delta functions

provides that

provides that

|

(6.5) |

for every continuous function  . We think of a delta function

as having zero width and unit area (§B.10).

. We think of a delta function

as having zero width and unit area (§B.10).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... frequency.6.4

- This is

not as confusing as one might think at first. When the frequency

range is

to

to  , normalized radian frequency is being used

(radians per sample). When the range is

, normalized radian frequency is being used

(radians per sample). When the range is  to

to  , it is

normalized frequency (cycles per sample). The unnormalized case (true

physical radian frequency in radians per second) usually only arises

in applications.

, it is

normalized frequency (cycles per sample). The unnormalized case (true

physical radian frequency in radians per second) usually only arises

in applications.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

moment.6.5

- See §B.17 for an example of this regarding the

uncertainty principle.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ....6.6

- A standard notation for

fundamental frequency is ``

'' (or

'' (or  ). This comes from the

speech analysis community, where usually

). This comes from the

speech analysis community, where usually  ,

,  , and so on,

refer to the formant frequencies (resonance peak frequencies)

of the vocal tract. When not working with formants, it is convenient

to define the fundamental frequency as

, and so on,

refer to the formant frequencies (resonance peak frequencies)

of the vocal tract. When not working with formants, it is convenient

to define the fundamental frequency as  , so that the frequency of

the

, so that the frequency of

the  th harmonic is

th harmonic is

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... periodic.6.7

- Most plucked strings can be

considered very nearly harmonic. Piano strings, however, are

significantly

stiff so that they exhibit audible inharmonicity--the partial

overtone series is stretched [77,267].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

exactly.6.8

- One situation in which minimum orthogonal spacing

works well is when the signal is known to be exactly periodic, and

the period is accurately measured using a fundamental-frequency

estimator (§10.1). In this case, we can resample the

periodic signal to obtain an exact integer number of samples per

period, and a rectangular window can be set to exactly one period in

length. In this situation, each DFT coefficient is proportional to

a Fourier series coefficient (defined in Chapter 2),

and the peak frequencies are known to be integer multiples of the

fundamental frequency, so no peak interpolation is needed at all.

In other words, the fundamental frequency estimator takes care of

locating all the peaks in frequency: Resampling to an integer period

in the time domain corresponds to resampling the spectrum at each

main-lobe peak in the frequency domain.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... bins6.9

- Here

we mean fractional bins when

is not an integer.

is not an integer.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

applications.6.10

- A tuning error of

% is about ``two

cents'', where a cent is defined as a hundredth of a semitone, or

% is about ``two

cents'', where a cent is defined as a hundredth of a semitone, or

. Most people cannot detect tuning

errors of only two cents, unless some kind of interference effect is

involved, in which case the frequency error translates to a slowly

modulated amplitude envelope.

. Most people cannot detect tuning

errors of only two cents, unless some kind of interference effect is

involved, in which case the frequency error translates to a slowly

modulated amplitude envelope.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

line.6.11

- We encountered least-squares optimization for FIR

filter design in §4.10.3.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

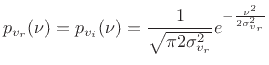

- ... distributed6.12

- The

Gaussian distribution is also called the normal distribution,

or ``bell curve.'' By the ``central limit theorem'' (§D.9.1),

any sum of independent random variables becomes Gaussian in the

limit. Therefore, filtered noise is usually well modeled as

Gaussian, since the filtering typically adds many random variables

together. See Appendix D for more about the Gaussian

distribution.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

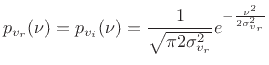

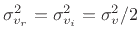

- ...

by6.13

- The real and imaginary parts of

are

independently distributed according to the more familiar Gaussian

density function

are

independently distributed according to the more familiar Gaussian

density function

|

(6.45) |

where

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... autocorrelation,7.1

- Note that there are many

possible biased estimates of the true autocorrelation

function. However, we will consider only one of them in this book.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... ``complicated''.7.2

- An interesting discussion

of the meaning of randomness is given in Knuth

[131, vol. II].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... function.7.3

- In Octave,

it is necessary to install the add-on package octave-forge to

obtain this and other signal processing functions.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ....7.4

- Note that we

are assuming

is zero mean. Otherwise, the sample variance would be

defined with the mean subtracted out, as discussed further in

§C.1.10. When the mean is zero, a correlation may be called a

covariance.

is zero mean. Otherwise, the sample variance would be

defined with the mean subtracted out, as discussed further in

§C.1.10. When the mean is zero, a correlation may be called a

covariance.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... mean.7.5

- Note that we are not

averaging the PSD to get the total variance, but instead

summing it. This is why the

factor in the IDFT above

is associated with

factor in the IDFT above

is associated with  and why the IDFT is also written as an

integral with respect to a Hertz frequency axis.

and why the IDFT is also written as an

integral with respect to a Hertz frequency axis.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... data.7.6

- A trend is typically estimated using linear

regression. That is, a straight line is fit through the data in a

least squares sense. (See the function polyfit in Matlab or

Octave.)

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...Kay88:7.7

-

The division by

can be seen as part of the implicit

autocorrelation calculation. It normalizes the peak of the

implicit Bartlett window on the autocorrelation to 1,

as discussed further below. Alternatively, it may be interpreted as a

normalization of the Fourier transform itself, converting a power

spectrum (squared-magnitude FFT) to a normalized power spectrum

(NDFT). Normalization is needed for stationary random processes since they

generally have infinite signal energy but finite average power; i.e.,

can be seen as part of the implicit

autocorrelation calculation. It normalizes the peak of the

implicit Bartlett window on the autocorrelation to 1,

as discussed further below. Alternatively, it may be interpreted as a

normalization of the Fourier transform itself, converting a power

spectrum (squared-magnitude FFT) to a normalized power spectrum

(NDFT). Normalization is needed for stationary random processes since they

generally have infinite signal energy but finite average power; i.e.,

grows without bound as

grows without bound as  increases.

increases.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... correlated.7.8

- An exception is when white noise is

filtered using an allpass filter, in which case the output signal is

still white noise.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... noise|textbf.7.9

- For a more

formal development, see the Wold decomposition theorem.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... noise7.10

- The term ``pink noise'' indicates that the

spectrum is more intense at low frequencies than at high frequencies.

This makes sense since the color pink is heavier in the red end of the

spectrum compared with white which balances all colors equally.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...VossAndClarke78,7.11

- Physical phenomena exhibiting a

power spectral density law include noise in vacuum tubes, carbon resistors,

transistor junctions, metal films, ionic solutions, films at the

superconducting transition, Josephson junctions, nerve membranes,

cosmic background radiation distribution, sunspot activity, and the

flood levels of the river Nile

[294]. In addition, the sub-audio short-time power

fluctuations in music (i.e., below the audible frequencies starting at 20 Hz) have been shown to follow the

power spectral density law include noise in vacuum tubes, carbon resistors,

transistor junctions, metal films, ionic solutions, films at the

superconducting transition, Josephson junctions, nerve membranes,

cosmic background radiation distribution, sunspot activity, and the

flood levels of the river Nile

[294]. In addition, the sub-audio short-time power

fluctuations in music (i.e., below the audible frequencies starting at 20 Hz) have been shown to follow the  characteristic, especially classical music [294].

characteristic, especially classical music [294].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... correctly.8.1

- In the Matlab

Signal Processing Toolbox, the argument 'periodic' should be

included when creating the window.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

integer.8.2

- Actually, non-integer

can be accommodated by

rotating among a set of windows obtained by sampling the underlying

continuous window at different phases.

can be accommodated by

rotating among a set of windows obtained by sampling the underlying

continuous window at different phases.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... limited.8.3

- This is of course the Fourier dual

of saying that the uniform sampling of a time-domain signal is

information-preserving provided the signal is properly bandlimited

(in the frequency domain).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... magnitude.8.4

- The spectrogram is often called a

sonogram when applied to audio signals.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... STFT.8.5

- Perfect reconstruction

is also possible in principle using

as large as

as large as  with the

Hamming window. However, this requires dividing out the amplitude

modulation given by the sum of Hamming windows displaced by

with the

Hamming window. However, this requires dividing out the amplitude

modulation given by the sum of Hamming windows displaced by  (see

Eq.(7.2)). In practice,

(see

Eq.(7.2)). In practice,  (50% overlap) is the largest hop size

used with the Hamming window because it is the largest value that

preserves the constant-overlap-add (COLA) property. We will

learn in Chapter 9 that

(50% overlap) is the largest hop size

used with the Hamming window because it is the largest value that

preserves the constant-overlap-add (COLA) property. We will

learn in Chapter 9 that  (75% overlap) is significantly

more robust than 50% overlap, and is recommended when spectral

modifications are to be carried out on the STFT data.

(75% overlap) is significantly

more robust than 50% overlap, and is recommended when spectral

modifications are to be carried out on the STFT data.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... SPL.8.6

- A listening-level slider would be nice to have in

the Graphical User Interface (GUI) for a loudness spectrogram.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

bank.8.7

- Note that the FFTs are effectively downsampled by this

operation, with the highest ``frequency-domain sampling rate''

occurring at the lowest frequency of the band. Therefore, the FFT

length can be set by matching the adjacent auditory filter spacing to

the low-frequency bin spacing of the FFT at the lower edge of the

frequency range covered by that FFT). In fact, one very large FFT

could be used in which the low-frequency bin spacing is approximately

equal to the spacing of the center-frequencies of the auditory

filter-bank channels at the low-frequency extreme.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... level.8.8

- Downloading http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/sasp/hw/SteveJobsHi.wav

and listening at a very low level (approximately 20 dB SPL) verifies that

indeed this sound example sounds like ``Hi...ee-jah,'' in

qualitative agreement with the sone loudness curve in Fig.7.9.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... constant.8.9

- Envelope

followers in sound processing classically

behave this way as well [109]. The amplitude envelope is

allowed to increase instantaneously, but it floats down with some time

constant that can be adjusted.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...MDFT,9.1

- https://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/mdft/Convolution_Theorem.html

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...).9.2

- These results were obtained using the

fft function in Matlab v5.2 running on a Windows

PC with an 800MHz Athlon CPU.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... 2011,9.3

- Octave on a Fedora 15

64-bit Linux machine (built in 2009) with an Intel Core i7-860

quad-core CPU running at 2.8 GHz

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...MDFT9.4

- https://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/mdft/Fast_Fourier_Transform_FFT.html

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

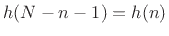

- ... filter.9.5

- As discussed in [261, Chapter 11],

an FIR filter having impulse response

is said to be linear

phase when its impulse response is symmetric about some point in time, e.g.,

is said to be linear

phase when its impulse response is symmetric about some point in time, e.g.,

, for

, for  , where

, where  is the length of the FIR filter.

is the length of the FIR filter.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... (COLA)9.6

- The acronym

COLA is not standard in signal processing, although OLA might be

recognized by many. When writing a paper, acronyms should always be

spelled out on first use, even for surely recognized acronyms such as

``FFT''.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... filter|textbf.10.1

- Low-power

applications such as RFID chips use cascaded integrated comb

filters (CIC filters) in their sampling-rate

converters.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... filter|textbf.10.2

- In ordinary sampling theory

[270],

each sample of a time-domain signal determines the scaling and

location of a sinc function for all time in the underlying

continuous-time signal represented by the samples. The dc sampling

filter described here is the Fourier dual of the time-domain sinc

function corresponding to a single sample in time.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

demodulation|textbf.10.3

- We use the term ``demodulation'' when frequencies

are translated from high to low (

to 0 in this case).

to 0 in this case).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...).10.4

- We

also implicitly assumed that the DFT size

was not smaller than the

window length

was not smaller than the

window length  .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... modifications.10.5

- The term

FBS modifications refers to changing the gain and/or phase

of the time-domain signal coming out of a filter-bank channel. This

is distinct from OLA modifications in which a spectrum is

altered, inverse transformed, and overlap-added into an output buffer.

Multiplicative OLA modifications are exact (no aliasing) when the

zero-padding in the time domain is sufficient. FBS modifications are

not provided zero-padding in the time domain, and for

there is

aliasing in the channel signals.

there is

aliasing in the channel signals.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

algorithm11.1

- This algorithm was developed by the author circa

1996 for vibrating-string fundamental frequency measurement. It has

been found to work quite well on the middle third (or so) of plucked

string recordings. An extension to stiff strings (stretched

partial overtone frequencies) is described in [266].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...MuellerEtAl11,KlapuriMohonk05,KlapuriSAP03,Klapuri01.11.2

- Klapuri's publications home page as of this writing:

http://www.elec.qmul.ac.uk/people/anssik/publications.htm

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... retrieval|textbf11.3

- For an introduction

to MIR, see, e.g., recent proceedings of the International Conference

on Music Information Retrieval (ISMIR) or Music Information

Retrieval Evaluation eXchange (MIREX) conference.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

construction,11.4

- A matrix is said to be

Toeplitz if the

]th

entry can be expressed as a function of

]th

entry can be expressed as a function of  . A Toeplitz matrix is

constant along all diagonals.

. A Toeplitz matrix is

constant along all diagonals.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

recursion.11.5

-

http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/filters/Computing_Reflection_Coefficients.html

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... hearing:11.6

- Due to nonlinearities in hearing

[179,306], it is not always valid to truncate

the summation at the high-frequency hearing limit. For complete

generally,

should be extended to the highest frequency

present in the signal

should be extended to the highest frequency

present in the signal  , since inaudible frequencies can give

rise to audible components at the output of a nonlinearity.

, since inaudible frequencies can give

rise to audible components at the output of a nonlinearity.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... overtone.11.7

- The

term overtone or partial overtone is generally used to

mean a sinusoidal component which is not harmonically related to the

fundamental frequency.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... ways.11.8

- Frequency

modulation is the time-derivative of phase modulation.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...McAulayQuatieri86.11.9

- An interesting avenue for future

research is the pursuit of new spectral-modeling primitives and

operators which are generally useful and compact for modeling

important aspects of sound.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...SmithSerra.11.10

- Higher-order interpolations of so-called

envelope break-points were also developed at CCRMA in the

late 1970s (e.g., using cubic splines), but for tonal sounds,

linear interpolation is usually sufficient, and the higher-order

envelopes did not see much use, presumably due to the greater

complexity of dealing with them coupled with the lack of significant

benefit.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... STFT|textbf,11.11

- Extension to multiresolution FFT analysis was an

important step in obtaining artifact-free analysis and resynthesis

of polyphonic audio sources. Previously, sinusoidal and S+N

modeling had been confined to monophonic sources, such as voice, or

a single instrument, etc.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... band11.12

- See

Appendix E for a definition of Bark bands (classical critical bands of

hearing).

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...Ellis02-pvoc,HejnaAndMusicus9111.13

- Synchronous

Overlap-Add, Fixed Synthesis [104]--a

time-domain method reminiscent of the Eventide ``Harmonizer,''

based on an overlap-add decomposition of the time waveform, with

input windows shifted and output windows regularly spaced for a

fixed output synthesis window-rate. SOLA-FS is said to be more

computationally efficient than SOLA

[240,280].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... bank|textbf.11.14

- In Beranek's Acoustics [15, pp. 333-334], the ``one-third octave-band analyzer'' is

defined as the 25-band filter bank having the spectral partition

points (in Hz) [20, 45, 57, 71, 90, 114,

142, 180, 228, 284, 360, 456, 568, 720, 912, 1136, 1440, 1824, 2272,

2880, 3648, 4544, 5760, 7296, 9088, 11520].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... bank|textbf,11.15

- An

``octave-band analyzer'' is defined in [15, p. 333] as

the 8-band filter bank having the spectral partition points [37.5,

75, 150, 300, 600, 1200, 2400, 4800, 10000] Hz.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... channels.11.16

- Thanks to Jeurgen Herre for

mentioning this reference.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...dtftalias):11.17

- A more efficient implementation can use

reshape and sum.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... general.11.18

- When the FFT window is

a length N rectangular window, then alias(Hk .* X, Nk) ==

BandK, as defined above, and there is no aliasing after all.

More precisely, the aliased spectral samples all happen to be zeros

of the window transform (which is an aliased sinc function, as

defined in §3.1). These zeros depend on the

window-length being N (no zero-padding), and on the window-type

being rectangular (``no window'').

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

bank.11.19

- Do not confuse the Octave program--a free, open-source

implementation of the matlab language--with the musical

octave: a frequency interval spanning a factor of two.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... domain.11.20

- The samples are

connected by straight lines to make them visible. The true responses

for the left two bands are aliased sinc functions (asinc). The next

octave up is a sum of two asincs, and the rightmost band (top

octave) is a sum of four asincs. A properly interpolated frequency

response for this filter bank is shown in

Fig.10.33.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...dcells11.21

- http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/sasp/dcells.m

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...dcells2spec11.22

- http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/sasp/dcells2spec.m

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... wide.11.23

- We do not really have to restrict

consideration to powers of two, as there are many fast Fourier

transform algorithms for various composite and prime lengths

[80,289].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... samples''11.24

- Spectral samples are

defined here as ``bin numbers plus 1'', that is, spectral samples

are numbered from 1 as in matlab, rather than from 0, as in the

signal processing literature.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

website.11.25

-

http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/pdf/SMS.pdf

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ....12.1

- We will relax the restriction

in the next

section. The only reason for the restriction now is to avoid a

different system definition for

in the next

section. The only reason for the restriction now is to avoid a

different system definition for  relative to what we'll derive

in the next section.

relative to what we'll derive

in the next section.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ....12.2

- The diagram-manipulation derivation in

§11.1.3 would produce

subphase branches,

each scaled by

subphase branches,

each scaled by  , while here we have only

, while here we have only  subphase

branches, each feeding a length

subphase

branches, each feeding a length  FIR filter.

FIR filter.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

transients.12.3

- The Dolby AC-3 perceptual audio coding format,

which is formulated more directly as a transform coder (quantized

STFT), switches to a shorter FFT window when transients are detected

in the signal being encoded. The original Dolby AC-2 format used

length 512 FFT windows in a Princen-Bradley time-domain aliasing

cancellation scheme (sampling rate typically 44.1 kHz). The shorter

length for transients in AC-3 was chosen to be 256 samples, or half

the steady-state length [149, §4.1.4]. A special hybrid

window is needed for a smooth transition from steady-state to

transient processing, or vice versa.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... level.12.4

- One careful study found that 96-kbps AAC is

roughly equivalent to 128-kbps MP3, which is a 33% lower bitrate at

roughly the same quality level. [149, §4.1.8].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... transform|textbf.12.5

- The

of a

bandpass filter may be defined as its center-frequency divided by its

bandwidth [263].

of a

bandpass filter may be defined as its center-frequency divided by its

bandwidth [263].

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

bank|textbf,12.6

- The term ``dyad'' simply means ``two'', as

in monad, dyad, triad, tetrad,

. Thus, successive bands

in a dyadic filter bank are obtained using a frequency-scale factor of

two.

. Thus, successive bands

in a dyadic filter bank are obtained using a frequency-scale factor of

two.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... transforms:B.1

- See

§8.3.1 for the discrete-time case.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...MDFT,B.2

- http://ccrma.stanford.edu/~jos/mdft/Cauchy_Schwarz_Inequality.html

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... filter.B.3

- An allpass filter has unity gain and

arbitrary delay at each frequency.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...

Therefore,B.4

- Technically, the Fourier transform of the unit

step function

does not exist, since

does not exist, since  is not

integrable for any value of

is not

integrable for any value of  . However, its Laplace

transform

. However, its Laplace

transform

does exist in the right-half

does exist in the right-half  plane, and

the limit as

plane, and

the limit as

is well behaved and can be taken as the

definition of the Fourier transform. The same construction works for

is well behaved and can be taken as the

definition of the Fourier transform. The same construction works for

,

,

, and so on.

, and so on.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... orderB.5

- We will say that a function

is of order

is of order

if

there exists

if

there exists  and some positive constant

and some positive constant  such

that

such

that

for all

for all

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ....B.6

- Such a decomposition may be

constructed by differentiating to obtain

and defining

and defining

![$\displaystyle w^\prime_{\scriptscriptstyle\uparrow}(t)\isdef \left\{\begin{array}{ll} w^\prime , & w^\prime \geq 0 \\ [5pt] 0, & w^\prime <0 \\ \end{array} \right.$](img2589.png) |

(B.81) |

and similarly for

. (The derivatives may include impulses

corresponding to discontinuities in

. (The derivatives may include impulses

corresponding to discontinuities in  .)

.)

The quantity

![$ [w_{\scriptscriptstyle\uparrow}(b)-w_{\scriptscriptstyle\uparrow}(a)] + [w_{\scriptscriptstyle\downarrow}(b)-w_{\scriptscriptstyle\downarrow}(a)]$](img2591.png) is called the

total variation of

is called the

total variation of  on

on  ; if this value is finite,

then

; if this value is finite,

then  is said to be of

bounded variation on

is said to be of

bounded variation on  .

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ...impulse.C.1

- The impulse

may be defined as any ``function''

may be defined as any ``function''  for which

for which

|

(C.10) |

where  is assumed continuous at

is assumed continuous at  . A typical definition is

. A typical definition is

![$\displaystyle \delta(x) \isdef \lim_{\Delta \to 0} \left\{\begin{array}{ll} \frac{1}{\Delta}, & 0\leq x\leq \Delta \\ [5pt] 0, & \hbox{otherwise}. \\ \end{array} \right.$](img2629.png) |

(C.11) |

The impulse was introduced in Chapter 2 starting at §B.10.

See also [264,36,150] for further development.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... process.C.2

- The general class of stochastic processes for

which time averages equal ensemble averages is called ergodic

stochastic processes [201]. In this book, all

stochastic processes are assumed ergodic (and hence stationary)

because they can all be modeled as filtered white noise, where the

filter is stable, linear, and (at least approximately over short

durations) time-invariant. Furthermore, the driving noise can be

chosen to be Gaussian; see more advanced texts on stochastic

processes regarding distinctions that can arise in non-ergodic

cases.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... length.C.3

- Note

that 20 ms contains only one period of a sinusoid at 50 Hz, which is

above lower limit of pitch perception (the low note of the piano, A0,

is tuned to 22 Hz). It is therefore possible to encounter difficulty

resolving tones in the deep bass region of the audio spectrum. A 20

ms frame length works quite well, however, for telephone speech

processing, in which the nominal bandwidth is 200-3200 Hz; in this

case, a 20ms frame has at least four periods of the lowest frequency

present, and harmonic resolution is assured under the Hamming window.

In wideband audio work, a multiresolution analysis is often highly

preferable.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

- ... numbers.C.4

-

Two random events

and

and  are said to be

independent if the

probability of event

are said to be

independent if the

probability of event  and

and  occurring together equals the product

of the probability of event

occurring together equals the product

of the probability of event  times the probability of event

times the probability of event  .

Similarly, two random variables

.

Similarly, two random variables  and

and  are said to be

independent if the

probability that both

are said to be

independent if the

probability that both  and

and  equals the probability that

equals the probability that

times the probability that

times the probability that  , where

, where  and

and  are any

values that the respective random variables can assume. For purposes