Next: Maximum Group Velocity

Up: Applications in Vibrational Mechanics

Previous: Longitudinal and Torsional Waves

Plates

The equations of motion of a stiff plate are the (2+1)D generalization of those of a beam. We assume the plate to lie, when at rest, in the  plane, and to be of thickness

plane, and to be of thickness  ; the deflection

; the deflection  of the plate from its equilibrium state is assumed to be perpendicular to the

of the plate from its equilibrium state is assumed to be perpendicular to the  plane. The plate material has density

plane. The plate material has density  , as well as Young's modulus

, as well as Young's modulus  and Poisson's ratio

and Poisson's ratio  , all of which are assumed, for the sake of generality, to be smooth positive functions of

, all of which are assumed, for the sake of generality, to be smooth positive functions of  and

and  . In particular,

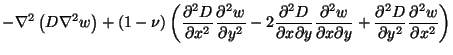

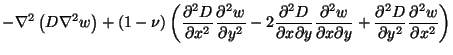

. In particular,  must be less than one-half. The classical development depends on neglecting rotational inertia effects and makes various assumptions analogous to the ``plane sections remain plane and perpendicular to the neutral axis'' hypothesis that was used as the basis for the Euler-Bernoulli beam model [77]. The resulting equation of motion [6,113] can be written as

must be less than one-half. The classical development depends on neglecting rotational inertia effects and makes various assumptions analogous to the ``plane sections remain plane and perpendicular to the neutral axis'' hypothesis that was used as the basis for the Euler-Bernoulli beam model [77]. The resulting equation of motion [6,113] can be written as

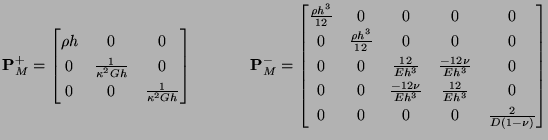

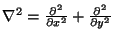

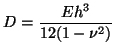

where

and used

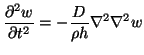

. If the material parameters and the thickness are constant, then

. If the material parameters and the thickness are constant, then

|

(5.31) |

which is easily seen to be a direct generalization of (5.2). As such, we expect to find the same anomalous behavior of the resulting propagation velocities, which can become infinitely large in the high-frequency limit. Numerical integration of these equations via a waveguide mesh proceeds along exactly the same lines as in the case of the Euler-Bernoulli beam; in particular, we find a restriction on the space step/time step ratio similar to those that resulted in §5.1.2.

Because the development is so similar to the (1+1)D case, we will proceed directly to the more refined model of plate motion, which is a direct generalization of the Timoshenko theory for beams. First proposed by Mindlin, the model [77,120], can be written as system of eight PDEs [173]:

|

(5.32a) |

|

|

(5.33a) |

|

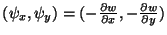

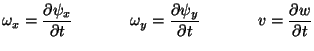

Here, we have written

where  is the transverse displacement of the plate, and

is the transverse displacement of the plate, and

is the pair of angles giving the orientation of the sides of a deformed differential element of the plate with respect to the perpendicular. (In the classical theory, for which cross-sections of the plate are assumed to remain parallel to the plate normal, we have

is the pair of angles giving the orientation of the sides of a deformed differential element of the plate with respect to the perpendicular. (In the classical theory, for which cross-sections of the plate are assumed to remain parallel to the plate normal, we have

.) In addition, we have the shear forces

.) In addition, we have the shear forces

and moments

and moments

, which are the (2+1)D generalizations of

, which are the (2+1)D generalizations of  and

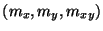

and  . The system (5.31)-(5.32) as a whole is known as Mindlin's system, although it is more commonly written s a system of three second-order equations in the variables

. The system (5.31)-(5.32) as a whole is known as Mindlin's system, although it is more commonly written s a system of three second-order equations in the variables  ,

,  and

and  [77]. We have written Mindlin's system so that it is easy to see the decomposition into two separate subsystems, one in

[77]. We have written Mindlin's system so that it is easy to see the decomposition into two separate subsystems, one in

and the other in

and the other in

, with the coupling occurring via constant-proportional terms in

, with the coupling occurring via constant-proportional terms in

,

,

,

,  and

and  . In particular, subsystem (5.31) is similar to the lossless parallel-plate system (see §4.4), except for the coupling terms.

. In particular, subsystem (5.31) is similar to the lossless parallel-plate system (see §4.4), except for the coupling terms.

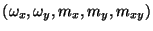

It is easy to see that this system is not, as written, symmetric hyperbolic. It is easy to symmetrize it by taking sums and differences of (5.32c) and (5.32d), in which case we get, in terms of the variable

![$ {\bf w} = [v, q_{x}, q_{y}, \omega_{x}, \omega_{y}, m_{x}, m_{y}, m_{xy}]^{T}$](img2481.png) ,

,

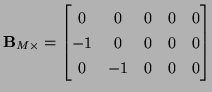

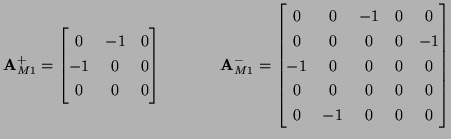

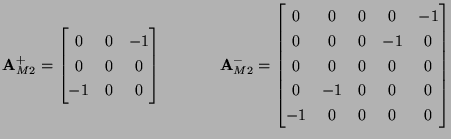

where the  stands for zero entries, and

stands for zero entries, and

|

(5.36) |

|

(5.37) |

The system defined by (5.33) is lossless, due to the anti-symmetry of

. Also, note that

. Also, note that

is positive definite (recall that

is positive definite (recall that  is positive, and less than one-half), but not diagonal

is positive, and less than one-half), but not diagonal ; this did not come up in any of the systems we have looked at previously, and will have interesting consequences in the circuit representations in the next section.

; this did not come up in any of the systems we have looked at previously, and will have interesting consequences in the circuit representations in the next section.

Subsections

Next: Maximum Group Velocity

Up: Applications in Vibrational Mechanics

Previous: Longitudinal and Torsional Waves

Stefan Bilbao

2002-01-22

![]() ,

,