|

|

|

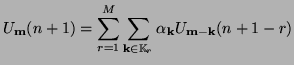

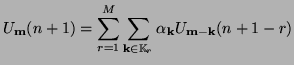

A particular form of the amplification polynomial equation which will appear frequently in our subsequent treatment of finite difference schemes for the wave equation is that of a simple two-step centered difference approximation, namely

|

It is important to realize, however, that the condition that these roots

![]() be bounded by unity is necessary, but not sufficient to ensure no growth in the

be bounded by unity is necessary, but not sufficient to ensure no growth in the ![]() norm of the solution; this point has not been addressed in the finite difference treatment of waveguide meshes. In fact, as shown in §4.3.4, the simple centered difference approximation to the wave equation admits linearly growing solutions.

norm of the solution; this point has not been addressed in the finite difference treatment of waveguide meshes. In fact, as shown in §4.3.4, the simple centered difference approximation to the wave equation admits linearly growing solutions.

This behavior can be examined in the spectral domain as we will now show, as per [176]. Notice that the solutions (A.6) of the amplification polynomial equation for the two-step scheme can coincide if, and only if at some frequency

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() ,

,

![]() , in which case we have

, in which case we have

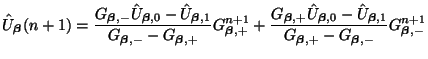

![]() . The evolution of the particular spatial frequency component at frequency

. The evolution of the particular spatial frequency component at frequency

![]()

![]() can be written as

can be written as

Strikwerda does not classify such linear growth as unstable, because the wave equation itself admits, in addition to traveling wave solutions, a solution which grows linearly with time![]() . For the physical modeling of musical instruments and acoustic spaces, however (the problems to which finite difference schemes of the form to be discussed shortly are often applied), such solutions are nonphysical and definitely not acceptable. These comments concerning this mild linear instability apply to schemes in unbounded domains; when boundary conditions are present, further analysis will be required.

. For the physical modeling of musical instruments and acoustic spaces, however (the problems to which finite difference schemes of the form to be discussed shortly are often applied), such solutions are nonphysical and definitely not acceptable. These comments concerning this mild linear instability apply to schemes in unbounded domains; when boundary conditions are present, further analysis will be required.

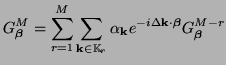

In order to simplify the analysis of these schemes, we mention that for difference schemes for the wave equation, it is often possible to write

For certain schemes (in particular, the interpolated schemes to be discussed in §A.2.2 and §A.3.3), the function

![]() depends on several parameters. Condition (A.8) tells us the the range of parameters over which our scheme is stable, and over the stability region, condition (A.9) gives us a maximum time step

depends on several parameters. Condition (A.8) tells us the the range of parameters over which our scheme is stable, and over the stability region, condition (A.9) gives us a maximum time step ![]() , in terms of the grid spacing

, in terms of the grid spacing ![]() .

.