Next: Other MD Elements

Up: MD Circuit Elements

Previous: MD Circuit Elements

The MD Inductor

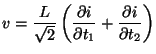

Consider the following (partial) differential equation:

|

(3.33) |

where  is a positive constant, and

is a positive constant, and  , for any

, for any  ,

,

is a coordinate defined by transformation (3.21). We now have

is a coordinate defined by transformation (3.21). We now have

and

and

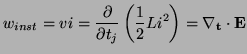

. Considered as an MD one-port, the instantaneous applied power will be

. Considered as an MD one-port, the instantaneous applied power will be

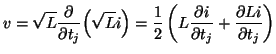

if we also define the stored energy flux  to be

to be

|

(3.34) |

where

is a column unit vector in the

is a column unit vector in the  direction. If

direction. If  , this is indeed a positive semi-definite vector function of the current across the one port. (3.34) defines a passive (in fact lossless) element in the sense of (3.29), henceforth called an MD-inductor, of inductance

, this is indeed a positive semi-definite vector function of the current across the one port. (3.34) defines a passive (in fact lossless) element in the sense of (3.29), henceforth called an MD-inductor, of inductance  and direction

and direction  .

.

This equation resembles that which defines the voltage/current relation in an inductor with inductance  , the exception being that the integration variable is no longer time, but

, the exception being that the integration variable is no longer time, but  , a mixed space-time variable. In fact, the discretization procedure is identical to that of the lumped case, as we shall see, but for illustrative purposes, we will derive the multidimensional wave digital one-port. The important thing to note here is that even though (3.34) is defined over a

, a mixed space-time variable. In fact, the discretization procedure is identical to that of the lumped case, as we shall see, but for illustrative purposes, we will derive the multidimensional wave digital one-port. The important thing to note here is that even though (3.34) is defined over a  -dimensional domain with coordinates

-dimensional domain with coordinates  , it is solved (given

, it is solved (given  , say) as a series of one-dimensional integrations (since (3.34) must hold for all values of t).

, say) as a series of one-dimensional integrations (since (3.34) must hold for all values of t).

We can immediately approximate (3.34) by the MD trapezoid rule [62] as

|

(3.35) |

where

.

.  is interpreted as the step-size.

Assuming that we have uniformly sampled the

is interpreted as the step-size.

Assuming that we have uniformly sampled the  plane as in §3.3, with grid spacings

plane as in §3.3, with grid spacings

, we now define the grid functions

, we now define the grid functions

and

and

where

where

![$ {\bf n} = [n_{1},\hdots, n_{k}]^{T}$](img657.png) is an integer-valued vector. We intend to use them to approximate

is an integer-valued vector. We intend to use them to approximate

![$ v({\bf t}=[n_{1}T_{1},\hdots,n_{k}T_{k}]^{T})$](img658.png) and

and

![$ i({\bf t}=[n_{1}T_{1},\hdots n_{k}T_{k}]^{T})$](img659.png) , so we can immediately write the recursion

, so we can immediately write the recursion

|

(3.36) |

which approximates (3.34) to

.

.

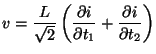

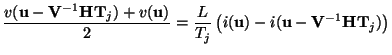

We can now introduce the wave variables,

which are also grid functions defined over  . As in the lumped case,

. As in the lumped case,  is an arbitrary positive number (here assumed constant). Inserting these wave variables into (3.37) yields, with the choice

is an arbitrary positive number (here assumed constant). Inserting these wave variables into (3.37) yields, with the choice

,

,

|

(3.37) |

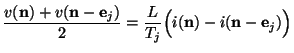

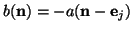

In terms of the untransformed coordinates (where we will perform the updating in a simulation), (3.36) becomes

|

(3.38) |

again to second order in the transformed spacing. The quantity

is the vector corresponding to the same shift, in the untransformed coordinates.

is the vector corresponding to the same shift, in the untransformed coordinates.

Take, for example the case of an inductor of direction  under the coordinate change defined by (3.19). A shift of

under the coordinate change defined by (3.19). A shift of

of

of  in direction

in direction  corresponds to a shift in the old coordinates of

corresponds to a shift in the old coordinates of

![$ (T_{1}/\sqrt{2})[1, 1/v_{0}]^{T}$](img673.png) . Referring to Figure 3.1(b), where we have chosen

. Referring to Figure 3.1(b), where we have chosen

, the instance of the wave variable

, the instance of the wave variable  entering the MD-inductor at point

entering the MD-inductor at point  exits, sign-inverted, as

exits, sign-inverted, as  at point

at point  . From this standpoint, MD-losslessness is obvious, since the MD-inductor merely shifts and sign-inverts an array of numbers.

. From this standpoint, MD-losslessness is obvious, since the MD-inductor merely shifts and sign-inverts an array of numbers.

One point requires some clarification; the MD inductor as defined by (3.34) is MD-passive for constant  , and for a transformed coordinate

, and for a transformed coordinate  ,

,

. In problems for which material parameters have some spatial variation, some of the MD circuit elements that we will require will, as a rule, have some spatial dependence. If

. In problems for which material parameters have some spatial variation, some of the MD circuit elements that we will require will, as a rule, have some spatial dependence. If  in (3.34) is a function of

in (3.34) is a function of  , then in general the equation does not describe an MD-passive one-port. More precisely, if

, then in general the equation does not describe an MD-passive one-port. More precisely, if  does not commute with

does not commute with

, then the application of the trapezoid rule to (3.34) does not yield the simple wave relationship (3.38). This begs the question, then, of how the trapezoid rule can be applied to circuit elements which are not LSI (which we will require in order to numerically integrate systems with spatial material parameter variation).

, then the application of the trapezoid rule to (3.34) does not yield the simple wave relationship (3.38). This begs the question, then, of how the trapezoid rule can be applied to circuit elements which are not LSI (which we will require in order to numerically integrate systems with spatial material parameter variation).

For almost all the systems of interest in this thesis, it will be possible to consolidate any material parameter variation in circuit elements defined with respect to the pure time direction (recall that in our general symmetric hyperbolic system (3.1), such variation is confined to the coefficients of the time derivative term). For example, consider an inductor described by

|

(3.39) |

in the (1+1)D coordinates defined by (3.18). Here,  is strictly positive, but may be a function of

is strictly positive, but may be a function of  , and note that

, and note that  is not among the new coordinates defined by (3.18). Because

is not among the new coordinates defined by (3.18). Because  does commute with

does commute with

, it is still possible to apply the trapezoid rule, in the time direction, in order to get a wave relationship of the form of (3.38). The directional shift will then be along the time direction, and we need to be sure that the shift does in fact refer to another grid point--from Figure 3.1(b), we can see that this is in fact true (it is true for any of the coordinate systems discussed in §3.3). It is of course possible to include a pure time derivative among the new coordinates; this is done, for example, in the case of the embedding defined by coordinates (3.22), for which

, it is still possible to apply the trapezoid rule, in the time direction, in order to get a wave relationship of the form of (3.38). The directional shift will then be along the time direction, and we need to be sure that the shift does in fact refer to another grid point--from Figure 3.1(b), we can see that this is in fact true (it is true for any of the coordinate systems discussed in §3.3). It is of course possible to include a pure time derivative among the new coordinates; this is done, for example, in the case of the embedding defined by coordinates (3.22), for which  is simply

is simply  multiplied by a scaling factor. Nitsche [62] has called this the generalized trapezoid rule. Note, however, that if we write (3.40) as

multiplied by a scaling factor. Nitsche [62] has called this the generalized trapezoid rule. Note, however, that if we write (3.40) as

|

(3.40) |

it is not permissible to treat this as a series connection of two MD inductors--neither one is MD-passive, because  does not commute with either of the two directional derivatives.

does not commute with either of the two directional derivatives.

A more general definition of an inductor, suitable for use in time-varying or nonlinear problems is

|

(3.41) |

for any transformed coordinate  . In this case,

. In this case,  can depend on

can depend on  or even on

or even on  or

or  ; as long as we have

; as long as we have  and use power-normalized waves, the MD inductor defined by (3.42) is MD passive [48,85]. For constant

and use power-normalized waves, the MD inductor defined by (3.42) is MD passive [48,85]. For constant  , (3.42) reduces to (3.34). Circuit elements of this type appear in circuit networks for fluid dynamical systems [16,49,70,191], as well as in a vector-matrix context when dealing with the linearized Euler Equations [86]. We also note that passivity under time-varying conditions can be enforced as it has been done in digital waveguide networks [166]; it would appear that waveguide networks (to be discussed in depth in Chapter 4) could be generalized to include the nonlinear case in the same manner (see Appendix B for an interesting application of these ideas).

, (3.42) reduces to (3.34). Circuit elements of this type appear in circuit networks for fluid dynamical systems [16,49,70,191], as well as in a vector-matrix context when dealing with the linearized Euler Equations [86]. We also note that passivity under time-varying conditions can be enforced as it has been done in digital waveguide networks [166]; it would appear that waveguide networks (to be discussed in depth in Chapter 4) could be generalized to include the nonlinear case in the same manner (see Appendix B for an interesting application of these ideas).

Next: Other MD Elements

Up: MD Circuit Elements

Previous: MD Circuit Elements

Stefan Bilbao

2002-01-22

![]() , the exception being that the integration variable is no longer time, but

, the exception being that the integration variable is no longer time, but ![]() , a mixed space-time variable. In fact, the discretization procedure is identical to that of the lumped case, as we shall see, but for illustrative purposes, we will derive the multidimensional wave digital one-port. The important thing to note here is that even though (3.34) is defined over a

, a mixed space-time variable. In fact, the discretization procedure is identical to that of the lumped case, as we shall see, but for illustrative purposes, we will derive the multidimensional wave digital one-port. The important thing to note here is that even though (3.34) is defined over a ![]() -dimensional domain with coordinates

-dimensional domain with coordinates ![]() , it is solved (given

, it is solved (given ![]() , say) as a series of one-dimensional integrations (since (3.34) must hold for all values of t).

, say) as a series of one-dimensional integrations (since (3.34) must hold for all values of t).

![]() under the coordinate change defined by (3.19). A shift of

under the coordinate change defined by (3.19). A shift of

![]() of

of ![]() in direction

in direction ![]() corresponds to a shift in the old coordinates of

corresponds to a shift in the old coordinates of

![]() . Referring to Figure 3.1(b), where we have chosen

. Referring to Figure 3.1(b), where we have chosen

![]() , the instance of the wave variable

, the instance of the wave variable ![]() entering the MD-inductor at point

entering the MD-inductor at point ![]() exits, sign-inverted, as

exits, sign-inverted, as ![]() at point

at point ![]() . From this standpoint, MD-losslessness is obvious, since the MD-inductor merely shifts and sign-inverts an array of numbers.

. From this standpoint, MD-losslessness is obvious, since the MD-inductor merely shifts and sign-inverts an array of numbers.

![]() , and for a transformed coordinate

, and for a transformed coordinate ![]() ,

,

![]() . In problems for which material parameters have some spatial variation, some of the MD circuit elements that we will require will, as a rule, have some spatial dependence. If

. In problems for which material parameters have some spatial variation, some of the MD circuit elements that we will require will, as a rule, have some spatial dependence. If ![]() in (3.34) is a function of

in (3.34) is a function of ![]() , then in general the equation does not describe an MD-passive one-port. More precisely, if

, then in general the equation does not describe an MD-passive one-port. More precisely, if ![]() does not commute with

does not commute with

![]() , then the application of the trapezoid rule to (3.34) does not yield the simple wave relationship (3.38). This begs the question, then, of how the trapezoid rule can be applied to circuit elements which are not LSI (which we will require in order to numerically integrate systems with spatial material parameter variation).

, then the application of the trapezoid rule to (3.34) does not yield the simple wave relationship (3.38). This begs the question, then, of how the trapezoid rule can be applied to circuit elements which are not LSI (which we will require in order to numerically integrate systems with spatial material parameter variation).