Next: Interfaces Between Grids

Up: Digital Waveguide Networks

Previous: The (3+1)D Wave Equation

The Waveguide Mesh in General Curvilinear Coordinates

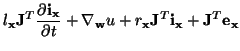

A generalization of the waveguide mesh to arbitrary curvilinear coordinates is useful in that it becomes possible to model boundary conditions which may not be simply aligned with a rectilinear grid. The resulting structure is quite similar to the interleaved forms discussed earlier, and for this reason we will give only a brief description of the coordinate transformation procedure. Consider the following system:

|

(4.113a) |

Here we may assume any number  of physical spatial coordinates

of physical spatial coordinates

![$ {\bf x} = [x_{1}, \hdots, x_{k}]^{T}$](img1883.png) , so that

, so that

![$ \nabla_{{\bf x}} = \frac{\partial}{\partial {\bf x}} = [\frac{\partial}{\partial x_{1}},\hdots, \frac{\partial}{\partial x_{k}}]^{T}$](img1884.png) .

.

and

and

are both assumed to be

are both assumed to be  -dimensional column vectors.

-dimensional column vectors.

,

,

,

,

and

and

are all positive functions of

are all positive functions of  (

(

and

and

are strictly positive), and

are strictly positive), and

and

and

are the source terms. If

are the source terms. If  is 1 or 2, then we have the transmission line or parallel-plate transmission line system respectively, and if

is 1 or 2, then we have the transmission line or parallel-plate transmission line system respectively, and if  , we have the system describing linear acoustic phenomena (assuming that the material parameters are constant).

, we have the system describing linear acoustic phenomena (assuming that the material parameters are constant).

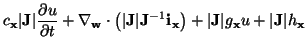

Consider the mapping

where

![$ {\bf w} = [w_{1}, \hdots, w_{k}]^{T}$](img1896.png) are the transformed coordinates. A rectilinear grid in the

are the transformed coordinates. A rectilinear grid in the  coordinates can be mapped to a curvilinear grid in the physical

coordinates can be mapped to a curvilinear grid in the physical  coordinates. We can then define the

coordinates. We can then define the  matrix of partial derivatives

matrix of partial derivatives  by

by

where

is the

is the  th component of

th component of  . We assume

. We assume  to be nonsingular everywhere in the problem domain (though this assumption may be relaxed as will mention later in this section) . Defining the differential operator

to be nonsingular everywhere in the problem domain (though this assumption may be relaxed as will mention later in this section) . Defining the differential operator

by

by

![$ \nabla_{{\bf w}} = \frac{\partial}{\partial {\bf w}} = [\frac{\partial}{\partial w_{1}},\hdots, \frac{\partial}{\partial w_{k}}]^{T}$](img1903.png) , it then follows [69] that

, it then follows [69] that

for any  column vector

column vector  . Here,

. Here,  is the so-called Jacobian determinant [172]. Using these relationships, the system (4.97) may be rewritten as

is the so-called Jacobian determinant [172]. Using these relationships, the system (4.97) may be rewritten as

or

|

(4.114a) |

where

and

System (4.98) is similar to (4.97), except that we now have ``vector'' inductance and resistance coefficients (note that both

and

and

are positive definite matrices, if

are positive definite matrices, if  is non-singular). In particular, it is still symmetric hyperbolic (see §3.2), so we may expect that it is possible to derive a waveguide structure.

is non-singular). In particular, it is still symmetric hyperbolic (see §3.2), so we may expect that it is possible to derive a waveguide structure.

Consider now the transformed system (4.98) in (2+1)D. If

is diagonal, then

is diagonal, then

and

and

will be as well; in this case, system (4.98) is in the same form

will be as well; in this case, system (4.98) is in the same form as the parallel-plate system in radial coordinates (4.82), so we need not discuss this case further here. Indeed, the radial system is a special case of (4.98) with

as the parallel-plate system in radial coordinates (4.82), so we need not discuss this case further here. Indeed, the radial system is a special case of (4.98) with

![$ {\bf w} = [\rho, \theta]^{T}$](img1929.png) and

and

On the other hand, if

is not diagonal (so that we are working in non-orthogonal or oblique coordinates), then the situation is more complex. Due to the cross-coupling between the components of

is not diagonal (so that we are working in non-orthogonal or oblique coordinates), then the situation is more complex. Due to the cross-coupling between the components of

through the matrices

through the matrices

and

and

, it will no longer be possible to stagger all the components of the solution; in particular, it will be necessary to use vector scattering junctions. Let us look at the case

, it will no longer be possible to stagger all the components of the solution; in particular, it will be necessary to use vector scattering junctions. Let us look at the case  , so that (4.98) are the equations of the parallel-plate system in the curvilinear coordinates

, so that (4.98) are the equations of the parallel-plate system in the curvilinear coordinates  . Furthermore, we will set

. Furthermore, we will set  and

and  . A centered difference approximation to (4.98), over grid points with coordinates

. A centered difference approximation to (4.98), over grid points with coordinates  and

and  , and at times

, and at times  for

for  ,

,  and

and  half-integer is

half-integer is

Here, we have the vector grid function

, which is a two-vector with components

, which is a two-vector with components

and

and

as well as the scalar grid function

as well as the scalar grid function

.

.

and

and

are second-order approximations to

are second-order approximations to

and

and

at the indicated grid points. The scheme above has been written so that it is clear that it can operate for

at the indicated grid points. The scheme above has been written so that it is clear that it can operate for  integer, and for

integer, and for  and

and  such that

such that  is integer; notice that

is integer; notice that  and

and  are calculated at alternating time instants and grid locations, but the components of

are calculated at alternating time instants and grid locations, but the components of  can not, in general, be calculated at separate locations.

can not, in general, be calculated at separate locations.  , again, is equal to

, again, is equal to  , and (4.99) will be a second-order accurate approximation to (4.98).

, and (4.99) will be a second-order accurate approximation to (4.98).

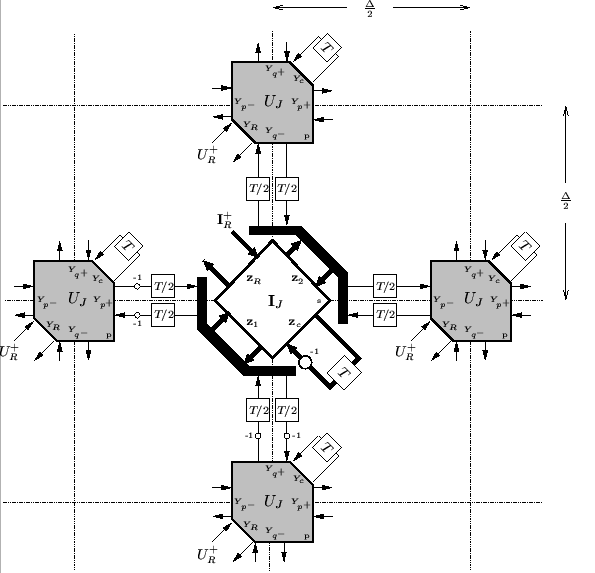

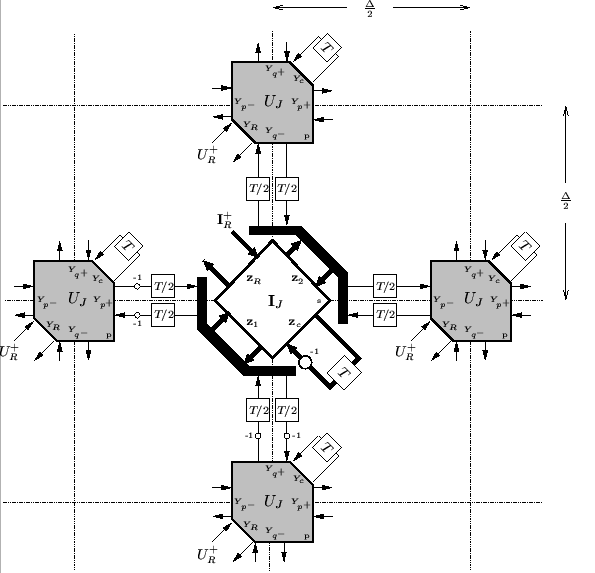

We will skip the tedious procedure of deriving a waveguide mesh, and simply present the resulting structure in Figure 4.34.

Figure 4.34:

(2+1)D DWN for the parallel-plate system (4.98) in general non-orthogonal curvilinear coordinates.

|

Junction vector currents

are calculated at the series vector scattering junctions; the black bars surrounding this junction in the figure are the splitting elements that were discussed in §4.2.6. Although we have not drawn them in the figure, there will be similar vector junctions at the four grid points neighboring any of the parallel junctions where the voltages

are calculated at the series vector scattering junctions; the black bars surrounding this junction in the figure are the splitting elements that were discussed in §4.2.6. Although we have not drawn them in the figure, there will be similar vector junctions at the four grid points neighboring any of the parallel junctions where the voltages  are calculated. This vector junction has four

are calculated. This vector junction has four  matrix impedances associated with it:

matrix impedances associated with it:

, the self-loop impedance,

, the self-loop impedance,

, the loss/source impedance, and

, the loss/source impedance, and

and

and

, which are constrained (see §4.2.6) to be

, which are constrained (see §4.2.6) to be

|

(4.116) |

The junction impedance

is defined to be the sum of these four matrices. The admittances at the parallel junctions are defined in a manner similar to those of the DWN in rectilinear coordinates. Also, we have the source voltage waves

is defined to be the sum of these four matrices. The admittances at the parallel junctions are defined in a manner similar to those of the DWN in rectilinear coordinates. Also, we have the source voltage waves

at the parallel junctions and vector source current waves

at the parallel junctions and vector source current waves

at the series junctions.

at the series junctions.

This DWN can be identified with the difference system (4.99) if we set

at the grid points for which such quantities are defined.

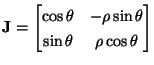

There are, of course, various realizations, depending on how the self-loop and connecting immittances are chosen. First, note that because

is not diagonal, it will not be possible to distribute it equally among the two connecting impedances

is not diagonal, it will not be possible to distribute it equally among the two connecting impedances

and

and

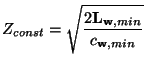

, which are constrained to be diagonal from (4.100). Thus a type II (current-centered) realization analogous to that which was discussed in the case of the rectilinear mesh will not be possible, even in the absence of losses and sources. A type I realization is certainly possible, but for brevity sake, we will only provide the settings for the type III DWN. Here all the connecting impedances are all set to be some constant value

, which are constrained to be diagonal from (4.100). Thus a type II (current-centered) realization analogous to that which was discussed in the case of the rectilinear mesh will not be possible, even in the absence of losses and sources. A type I realization is certainly possible, but for brevity sake, we will only provide the settings for the type III DWN. Here all the connecting impedances are all set to be some constant value  . This then implies that

. This then implies that

where

is the

is the  identity matrix. Requiring the positivity of

identity matrix. Requiring the positivity of  and the positive definiteness of

and the positive definiteness of

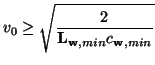

gives the constraint

gives the constraint

for

the minimum of

the minimum of

over parallel junction locations and

over parallel junction locations and

the minimum of the eigenvalues of

the minimum of the eigenvalues of

over series junction locations, and where we have made the choice

over series junction locations, and where we have made the choice

In general, this bound will depend on the choice of coordinates.

FDTD in general curvilinear coordinates has developed in a similar way; most formulations are slightly different in that they are based on a tensor density formulation [91,209] and employ a double set of variables (covariant and contravariant) in the non-orthogonal case; differencing involves interleaving these two sets of components at alternating time steps. They have also been used as a starting point for developing FDTD methods in ``local'' coordinates defined with respect to an automatically generated grid [72,73]. Curvilinear coordinate systems have been touched upon in the MDWD framework as well; An approach similar to the above is discussed in [69], and a tensor density formulation is given in [131].

Next: Interfaces Between Grids

Up: Digital Waveguide Networks

Previous: The (3+1)D Wave Equation

Stefan Bilbao

2002-01-22

![$\displaystyle [{\bf J}_{\alpha,\beta}] = \frac{\partial\zeta_{\alpha}}{\partial w_{\beta}}\hspace{0.5in}\alpha,\,\beta = 1,\hdots,k$](img1899.png)

![]() is diagonal, then

is diagonal, then

![]() and

and

![]() will be as well; in this case, system (4.98) is in the same form

will be as well; in this case, system (4.98) is in the same form![]() as the parallel-plate system in radial coordinates (4.82), so we need not discuss this case further here. Indeed, the radial system is a special case of (4.98) with

as the parallel-plate system in radial coordinates (4.82), so we need not discuss this case further here. Indeed, the radial system is a special case of (4.98) with

![]() and

and

![]() is not diagonal (so that we are working in non-orthogonal or oblique coordinates), then the situation is more complex. Due to the cross-coupling between the components of

is not diagonal (so that we are working in non-orthogonal or oblique coordinates), then the situation is more complex. Due to the cross-coupling between the components of

![]() through the matrices

through the matrices

![]() and

and

![]() , it will no longer be possible to stagger all the components of the solution; in particular, it will be necessary to use vector scattering junctions. Let us look at the case

, it will no longer be possible to stagger all the components of the solution; in particular, it will be necessary to use vector scattering junctions. Let us look at the case ![]() , so that (4.98) are the equations of the parallel-plate system in the curvilinear coordinates

, so that (4.98) are the equations of the parallel-plate system in the curvilinear coordinates ![]() . Furthermore, we will set

. Furthermore, we will set ![]() and

and ![]() . A centered difference approximation to (4.98), over grid points with coordinates

. A centered difference approximation to (4.98), over grid points with coordinates ![]() and

and ![]() , and at times

, and at times ![]() for

for ![]() ,

, ![]() and

and ![]() half-integer is

half-integer is

![]() is not diagonal, it will not be possible to distribute it equally among the two connecting impedances

is not diagonal, it will not be possible to distribute it equally among the two connecting impedances

![]() and

and

![]() , which are constrained to be diagonal from (4.100). Thus a type II (current-centered) realization analogous to that which was discussed in the case of the rectilinear mesh will not be possible, even in the absence of losses and sources. A type I realization is certainly possible, but for brevity sake, we will only provide the settings for the type III DWN. Here all the connecting impedances are all set to be some constant value

, which are constrained to be diagonal from (4.100). Thus a type II (current-centered) realization analogous to that which was discussed in the case of the rectilinear mesh will not be possible, even in the absence of losses and sources. A type I realization is certainly possible, but for brevity sake, we will only provide the settings for the type III DWN. Here all the connecting impedances are all set to be some constant value ![]() . This then implies that

. This then implies that