Next: Computational Considerations

Up: A Simple Scheme

Previous: Accuracy

Contents

Index

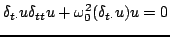

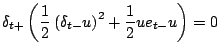

Beginning from the compact representation of the difference scheme given in (3.18), one may derive a discrete conserved energy similar to that obtained for the continuous problem in Section 3.1.2. Multiplying (3.18) by a discrete approximation to the velocity,

gives

gives

|

(3.34) |

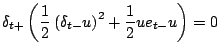

Employing the product identities given in Section 2.4.2 in the last chapter, one may immediately arrive at

|

(3.35) |

or

|

(3.36) |

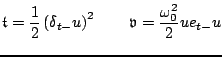

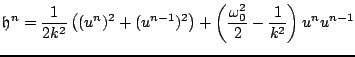

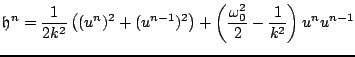

with

|

(3.37) |

and

and

are clearly approximations to the kinetic and potential energies,

are clearly approximations to the kinetic and potential energies,

and

and

respectively, for the continuous problem, as defined in (3.10).

respectively, for the continuous problem, as defined in (3.10).

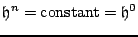

Equation (3.36) implies that the discrete time series

, which approximates the total energy

, which approximates the total energy

for the continuous time problem, is constant. Thus the scheme (3.18) is energy conserving, in a discrete sense. In other words,

for the continuous time problem, is constant. Thus the scheme (3.18) is energy conserving, in a discrete sense. In other words,

|

(3.38) |

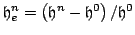

Though one might think that the existence of a discrete conserved energy would immediately imply good behaviour of the associated finite difference scheme, just as in the continuous time case, it is important to note that the discrete approximation to potential energy, given above in (3.37), is not necessarily positive, and thus neither is

. The determination of positivity conditions on

. The determination of positivity conditions on

leads directly to a numerical stability condition. Expanding out the operator notation, one may write the function

leads directly to a numerical stability condition. Expanding out the operator notation, one may write the function

at time step

at time step  as

as

|

(3.39) |

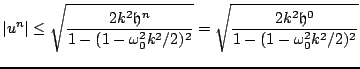

which is no more than a quadratic form in the variables  and

and  . Applying the results given in §2.4.3, one may show that the quadratic form above is positive definite when

. Applying the results given in §2.4.3, one may show that the quadratic form above is positive definite when

|

(3.40) |

which is exactly the condition (3.25) arrived at through frequency domain analysis. Under this condition, one further has that

|

(3.41) |

Just as in the case of frequency domain analysis, the solution may be bounded in terms of the initial conditions (or the initial energy) and the system parameters. In fact, the bound above is identical to that given in (3.29). See Problem 3.11.

It is important to make some comments about the nature of this numerical energy conservation property. In infinite precision arithmetic, the quantity

remains exactly constant, according to (3.38). That is, the discrete kinetic energy

remains exactly constant, according to (3.38). That is, the discrete kinetic energy

and potential energy

and potential energy

sum to the same constant, at any time step

sum to the same constant, at any time step  . See Figure 3.2(a). But in a finite precision computer implementation, there will be fluctuations in the total energy at the level of the least significant bit; such a fluctuation is shown, in the case of floating point arithmetic, in Figure 3.2(b). In this case, the fluctuations are on the order of

. See Figure 3.2(a). But in a finite precision computer implementation, there will be fluctuations in the total energy at the level of the least significant bit; such a fluctuation is shown, in the case of floating point arithmetic, in Figure 3.2(b). In this case, the fluctuations are on the order of  of the total energy, and the bit-quantization of these variations is clearly visible. Thus energy is conserved to machine accuracy.

of the total energy, and the bit-quantization of these variations is clearly visible. Thus energy is conserved to machine accuracy.

Figure:

(a) Variation of the discrete potential energy

(solid grey line), discrete kinetic energy

(solid grey line), discrete kinetic energy

(dotted grey line) and total discrete energy

(dotted grey line) and total discrete energy

(solid black line), plotted against time step

(solid black line), plotted against time step  , for the output of scheme (3.18). In this case, the values

, for the output of scheme (3.18). In this case, the values

and

and  were used, and scheme (3.18) was initialized with the values

were used, and scheme (3.18) was initialized with the values  and

and

. (b) Variation of the error in energy, defined, at time step

. (b) Variation of the error in energy, defined, at time step  , as

, as

, plotted as black points. Multiples of single bit variation are plotted as grey lines.

, plotted as black points. Multiples of single bit variation are plotted as grey lines.

|

The analysis of conservative properties of finite difference schemes is younger than frequency domain analysis, and, as a result, much less well-known. It is, however, far more powerful than the body of frequency domain analysis techniques which form the workhorse of scheme analysis. The energy method [102] is the name given to a class of analysis techniques which do not employ frequency domain concepts. The study of finite difference schemes which possess conservation properties (of energy, and other invariants) experienced a good deal of growth in the 1980s [101,188] and 1990s [139,244,91], and is related to more modern symplectic integration techniques [189,199].

Next: Computational Considerations

Up: A Simple Scheme

Previous: Accuracy

Contents

Index

Stefan Bilbao

2006-11-15

![]() , which approximates the total energy

, which approximates the total energy

![]() for the continuous time problem, is constant. Thus the scheme (3.18) is energy conserving, in a discrete sense. In other words,

for the continuous time problem, is constant. Thus the scheme (3.18) is energy conserving, in a discrete sense. In other words,

![]() . The determination of positivity conditions on

. The determination of positivity conditions on

![]() leads directly to a numerical stability condition. Expanding out the operator notation, one may write the function

leads directly to a numerical stability condition. Expanding out the operator notation, one may write the function

![]() at time step

at time step ![]() as

as

![]() remains exactly constant, according to (3.38). That is, the discrete kinetic energy

remains exactly constant, according to (3.38). That is, the discrete kinetic energy

![]() and potential energy

and potential energy

![]() sum to the same constant, at any time step

sum to the same constant, at any time step ![]() . See Figure 3.2(a). But in a finite precision computer implementation, there will be fluctuations in the total energy at the level of the least significant bit; such a fluctuation is shown, in the case of floating point arithmetic, in Figure 3.2(b). In this case, the fluctuations are on the order of

. See Figure 3.2(a). But in a finite precision computer implementation, there will be fluctuations in the total energy at the level of the least significant bit; such a fluctuation is shown, in the case of floating point arithmetic, in Figure 3.2(b). In this case, the fluctuations are on the order of ![]() of the total energy, and the bit-quantization of these variations is clearly visible. Thus energy is conserved to machine accuracy.

of the total energy, and the bit-quantization of these variations is clearly visible. Thus energy is conserved to machine accuracy.