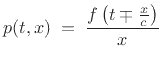

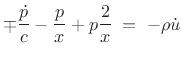

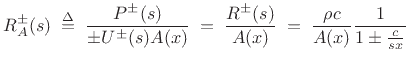

From Eq.(C.167) we have that the traveling-wave solution of the wave equation in spherical coordinates can be expressed as

where the minus sign is associated with an expanding spherical wave, and the plus sign corresponds to a converging wave. The spatial derivative of this function is

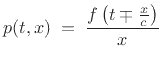

Referring to Fig.C.48, the area function ![]() can be

written for any cone in terms of the distance from its apex as

can be

written for any cone in terms of the distance from its apex as

for some

which is independent of the conical taper angle

. That is, one conical section of

a spherical wave is like any other, as it must be due to spherical

symmetry.

. That is, one conical section of

a spherical wave is like any other, as it must be due to spherical

symmetry.

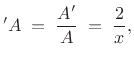

Substituting the logarithmic derivative of ![]() and

and ![]() from

Eq.(C.171) into the momentum-conservation equation

Eq. (C.169) yields

from

Eq.(C.171) into the momentum-conservation equation

Eq. (C.169) yields

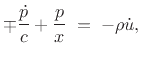

or

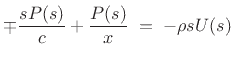

where the minus sign is for an expanding spherical wave, and the plus sign is for a converging spherical wave. Taking the Laplace transform of the above expression gives

in the case of zero initial conditions

We can now solve for the wave impedance in each direction, where

the wave impedance may be defined (§7.1)

as the Laplace transform of the traveling pressure divided by

the Laplace transform of the corresponding traveling velocity wave:

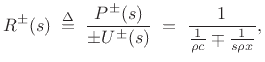

|

|||

|

where all of the upper signs or all of the lower signs are taken together, corresponding to expanding or converging spherical waves, respectively. In this notation, we may solve for the conical wave impedance as

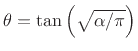

Along the frequency axis

where

is the radian spatial frequency, or wavenumber.

is the radian spatial frequency, or wavenumber.

Note that for a cylindrical tube, the wave impedance in both directions is

![]() , and there is no frequency dependence. A wavelength

or more away from the conical tip, i.e., for

, and there is no frequency dependence. A wavelength

or more away from the conical tip, i.e., for

![]() ,

where

,

where ![]() is the spatial wavelength, the wave impedance again approaches

that of a cylindrical bore. However, in conical musical instruments,

the fundamental wavelength is typically twice the bore length, so the

complex nature of the wave impedance is important throughout the bore and

approaches being purely imaginary near the mouthpiece. This is

especially relevant to conical-bore double-reeds, such as the bassoon.

is the spatial wavelength, the wave impedance again approaches

that of a cylindrical bore. However, in conical musical instruments,

the fundamental wavelength is typically twice the bore length, so the

complex nature of the wave impedance is important throughout the bore and

approaches being purely imaginary near the mouthpiece. This is

especially relevant to conical-bore double-reeds, such as the bassoon.

Writing the wave impedance as

the reader familiar with circuit theory (§7.2.3) will recognize this as the parallel combination of the wave impedance

Up to now, we have been defining wave impedance as pressure divided by particle velocity. In acoustic tubes, volume velocity is what is conserved at a junction between two different acoustic tube types. Therefore, in acoustic tubes, we define the wave impedance as the ratio of pressure to volume velocity

or, defining

as the time to propagate over the distance

as the time to propagate over the distance

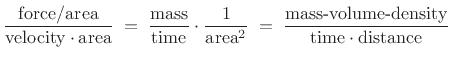

In this case, the equivalent mass is

![]() . It would perhaps be more satisfying if the equivalent mass in

the conical wave impedance were instead

. It would perhaps be more satisfying if the equivalent mass in

the conical wave impedance were instead

![]() which is the

mass of air contained in a cylinder of radius

which is the

mass of air contained in a cylinder of radius ![]() projected back to

the tip of the cone. However, the ``acoustic mass'' cannot be

physically equivalent to mechanical mass. To see this, consider that

the impedance of a mechanical mass is

projected back to

the tip of the cone. However, the ``acoustic mass'' cannot be

physically equivalent to mechanical mass. To see this, consider that

the impedance of a mechanical mass is ![]() which is in physical units

of mass per unit time, and by definition of mechanical impedance this

equals force over velocity. The impedance in an acoustic tube, on the

other hand, must be in units of pressure (force/area) divided by

volume velocity (velocity

which is in physical units

of mass per unit time, and by definition of mechanical impedance this

equals force over velocity. The impedance in an acoustic tube, on the

other hand, must be in units of pressure (force/area) divided by

volume velocity (velocity ![]() area) and this reduces to

area) and this reduces to

which is what we found.

The real part of the wave impedance corresponds to transportation of wave

energy, the imaginary part is a so-called ``reactance'' and does not

correspond to power transfer. Instead, it corresponds to a ``standing

wave'' which is created by equal and opposite power flow, or an

``evanescent wave'' (§C.8.2), which is a non-propagating,

exponentially decaying, limiting form of a traveling wave in which the

``propagation constant'' is purely imaginary due to being at a

frequency above or below a ``cut off'' frequency for the waveguide

[297,122]. Driving an ideal mass at the end of a

waveguide results in total reflection of all incident wave energy

along with a quarter-cycle phase shift. Another interpretation is

that the traveling wave becomes a standing wave at the tip of the

cone. This is one way to see how the resonances of a cone can be the

same as those of a cylinder the same length which is open on

both ends. (One might first expect the cone to behave like a

cylinder which is open on one end and closed on the other.) Because

the impedance approaches a purely imaginary zero at the tip, it looks

like a mass (with impedance

![]() ). The ``piston of air'' at

the open end similarly looks like a mass

[287].

). The ``piston of air'' at

the open end similarly looks like a mass

[287].