In §6.6, the ideal struck string was modeled as a simple initial velocity distribution along the string, corresponding to an instantaneous transfer of linear momentum from the striking hammer into the transverse motion of a string segment at time zero. (See Fig.6.10 for a diagram of the initial traveling velocity waves.) In that model, we neglected any effect of the striking hammer after time zero, as if it had bounced away at time 0 due to a so-called elastic collision. In this section, we consider the more realistic case of an inelastic collision, i.e., where the mass hits the string and remains in contact until something, such as a wave, or gravity, causes the mass and string to separate.

For simplicity, let the string length be infinity, and denote its wave

impedance by ![]() . Denote the colliding mass by

. Denote the colliding mass by ![]() and its speed

prior to collision by

and its speed

prior to collision by ![]() . It will turn out in this analysis that

we may approximate the size of the mass by zero (a so-called

point mass). Finally, we neglect the effects of gravity and

drag by the surrounding air. When the mass collides with the string,

our model must switch from two separate models (mass-in-flight and

ideal string), to that of two ideal strings joined by a mass

. It will turn out in this analysis that

we may approximate the size of the mass by zero (a so-called

point mass). Finally, we neglect the effects of gravity and

drag by the surrounding air. When the mass collides with the string,

our model must switch from two separate models (mass-in-flight and

ideal string), to that of two ideal strings joined by a mass ![]() at

at

![]() , as depicted in Fig.9.12. The ``force-velocity

port'' connections of the mass and two semi-infinite string endpoints

are formally in series because they all move together; that is,

the mass velocity equals the velocity of each of the two string

endpoints connected to the mass (see §7.2 for a fuller

discussion of impedances and their parallel/series connection).

, as depicted in Fig.9.12. The ``force-velocity

port'' connections of the mass and two semi-infinite string endpoints

are formally in series because they all move together; that is,

the mass velocity equals the velocity of each of the two string

endpoints connected to the mass (see §7.2 for a fuller

discussion of impedances and their parallel/series connection).

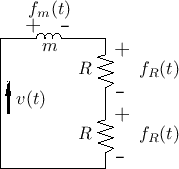

The equivalent circuit for the mass-string assembly after time zero is

shown in Fig.9.13. Note that the string wave impedance ![]() appears twice, once for each string segment on the left and right.

Also note that there is a single common velocity

appears twice, once for each string segment on the left and right.

Also note that there is a single common velocity ![]() for the two

string endpoints and mass. LTI circuit elements in series can be

arranged in any order.

for the two

string endpoints and mass. LTI circuit elements in series can be

arranged in any order.

|

From the equivalent circuit, it is easy to solve for the velocity ![]() .

Formally, this is accomplished by applying Kirchoff's Loop Rule, which

states that the sum of voltages (``forces'') around any series loop is zero:

.

Formally, this is accomplished by applying Kirchoff's Loop Rule, which

states that the sum of voltages (``forces'') around any series loop is zero:

Taking the Laplace transform10.9of Eq.(9.8) yields, by linearity,

where

For the mass, we have

![$\displaystyle f_m(t) = m\,a(t)\;=\; m\,\frac{d}{dt} v(t) \quad\longleftrightarrow\quad

F_m(s) = m\left[s\,V(s) - v_0\right],

$](img2059.png)

where we used the differentiation theorem for Laplace transforms [452, Appendix D].10.10Note that the mass is characterized by its impedance

Substituting these relations into Eq.(9.9) yields

That is, an equivalent problem formulation is to start with the mass at rest and in contact with the string, followed by striking the mass with an ideal hammer (impulse) that imparts momentum

|

An advantage of the external-impulse formulation is that the system

has a zero initial state, so that an impedance description

(§7.1) is complete. In other words, the system can be

fully described as a series combination of the three impedances ![]() ,

,

![]() (on the left), and

(on the left), and ![]() (on the right), driven by an external

force-source

(on the right), driven by an external

force-source

![]() .

.

Solving Eq.(9.10) for ![]() yields

yields

Since the Laplace transform of

We see that at time zero the mass velocity is

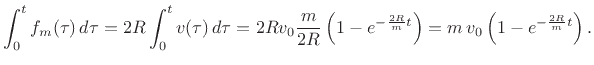

The displacement of the string at ![]() is given by the integral of

the velocity:

is given by the integral of

the velocity:

![$\displaystyle y(t,0) = \int_0^t v(\tau)\,d\tau = v_0\,\frac{m}{2R}\,\left[1-e^{-{\frac{2R}{m}t}}\right]

$](img2072.png)

where we defined the initial transverse displacement as

Thus, the final string displacement is proportional to both the ``hammer mass'' and the initial striking velocity; it is inversely proportional to the string wave impedance

The momentum of the mass before time zero is ![]() , and after time

zero it is

, and after time

zero it is

The force applied to the two string endpoints by the mass is given by

![]() . From Newton's Law,

. From Newton's Law,

![]() , we have that

momentum

, we have that

momentum ![]() , delivered by the mass to the string,

can be calculated as the time integral of applied force:

, delivered by the mass to the string,

can be calculated as the time integral of applied force:

Thus, the momentum delivered to the string by the mass starts out at zero, and grows as a relaxing exponential to

In a real piano, the hammer, which strikes in an upward (grand) or sideways (upright) direction, falls away from the string a short time after collision, but it may remain in contact with the string for a substantial fraction of a period (see §9.4 on piano modeling).