Next |

Prev |

Up |

Top

|

Index |

JOS Index |

JOS Pubs |

JOS Home |

Search

As a preview of things to come, note that one signal

4.16 is

projected onto another signal

4.16 is

projected onto another signal  using an inner

product. The inner product

using an inner

product. The inner product

computes the coefficient

of projection4.17 of

computes the coefficient

of projection4.17 of  onto

onto  . If

. If

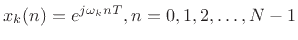

(a sampled, unit-amplitude, zero-phase, complex

sinusoid), then the inner product computes the Discrete Fourier

Transform (DFT), provided the frequencies are chosen to be

(a sampled, unit-amplitude, zero-phase, complex

sinusoid), then the inner product computes the Discrete Fourier

Transform (DFT), provided the frequencies are chosen to be

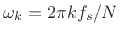

. For the DFT, the inner product is specifically

. For the DFT, the inner product is specifically

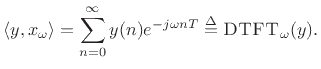

Another case of importance is the Discrete Time Fourier Transform

(DTFT), which is like the DFT except that the transform accepts an

infinite number of samples instead of only  . In this case,

frequency is continuous, and

. In this case,

frequency is continuous, and

The DTFT is what you get in the limit as the number of samples in the

DFT approaches infinity. The lower limit of summation remains zero

because we are assuming all signals are zero for negative time (such

signals are said to be causal). This means we are working with

unilateral Fourier transforms. There are also corresponding

bilateral transforms for which the lower summation limit is

. The DTFT is discussed further in

§B.1.

. The DTFT is discussed further in

§B.1.

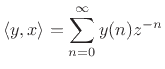

If, more generally,

(a sampled complex sinusoid with

exponential growth or decay), then the inner product becomes

(a sampled complex sinusoid with

exponential growth or decay), then the inner product becomes

and this is the definition of the  transform. It is a

generalization of the DTFT: The DTFT equals the

transform. It is a

generalization of the DTFT: The DTFT equals the  transform evaluated on

the unit circle in the

transform evaluated on

the unit circle in the  plane. In principle, the

plane. In principle, the  transform

can also be recovered from the DTFT by means of ``analytic continuation''

from the unit circle to the entire

transform

can also be recovered from the DTFT by means of ``analytic continuation''

from the unit circle to the entire  plane (subject to mathematical

disclaimers which are unnecessary in practical applications since they are

always finite).

plane (subject to mathematical

disclaimers which are unnecessary in practical applications since they are

always finite).

Why have a  transform when it seems to contain no more information than

the DTFT? It is useful to generalize from the unit circle (where the DFT

and DTFT live) to the entire complex plane (the

transform when it seems to contain no more information than

the DTFT? It is useful to generalize from the unit circle (where the DFT

and DTFT live) to the entire complex plane (the  transform's domain) for

a number of reasons. First, it allows transformation of growing

functions of time such as growing exponentials; the only limitation on

growth is that it cannot be faster than exponential. Secondly, the

transform's domain) for

a number of reasons. First, it allows transformation of growing

functions of time such as growing exponentials; the only limitation on

growth is that it cannot be faster than exponential. Secondly, the  transform has a deeper algebraic structure over the complex plane as a

whole than it does only over the unit circle. For example, the

transform has a deeper algebraic structure over the complex plane as a

whole than it does only over the unit circle. For example, the  transform of any finite signal is simply a polynomial in

transform of any finite signal is simply a polynomial in  . As

such, it can be fully characterized (up to a constant scale factor) by its

zeros in the

. As

such, it can be fully characterized (up to a constant scale factor) by its

zeros in the  plane. Similarly, the

plane. Similarly, the  transform of an

exponential can be characterized to within a scale factor

by a single point in the

transform of an

exponential can be characterized to within a scale factor

by a single point in the  plane (the

point which generates the exponential); since the

plane (the

point which generates the exponential); since the  transform goes

to infinity at that point, it is called a pole of the transform.

More generally, the

transform goes

to infinity at that point, it is called a pole of the transform.

More generally, the  transform of any generalized complex sinusoid

is simply a pole located at the point which generates the sinusoid.

Poles and zeros are used extensively in the analysis of recursive

digital filters. On the most general level, every finite-order, linear,

time-invariant, discrete-time system is fully specified (up to a scale

factor) by its poles and zeros in the

transform of any generalized complex sinusoid

is simply a pole located at the point which generates the sinusoid.

Poles and zeros are used extensively in the analysis of recursive

digital filters. On the most general level, every finite-order, linear,

time-invariant, discrete-time system is fully specified (up to a scale

factor) by its poles and zeros in the  plane. This topic will be taken

up in detail in Book II [71].

plane. This topic will be taken

up in detail in Book II [71].

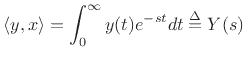

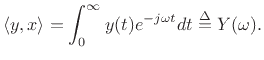

In the continuous-time case, we have the Fourier transform

which projects  onto the continuous-time sinusoids defined by

onto the continuous-time sinusoids defined by

, and the appropriate inner product is

, and the appropriate inner product is

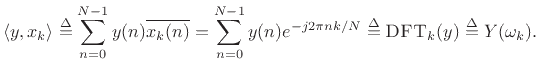

Finally, the Laplace transform is the continuous-time counterpart

of the  transform, and it projects signals onto exponentially growing

or decaying complex sinusoids:

transform, and it projects signals onto exponentially growing

or decaying complex sinusoids:

The Fourier transform equals the Laplace transform evaluated along the

`` axis'' in the

axis'' in the  plane, i.e., along the line

plane, i.e., along the line  , for

which

, for

which  . Also, the Laplace transform is obtainable from the

Fourier transform via analytic continuation. The usefulness of the Laplace

transform relative to the Fourier transform is exactly analogous to that of

the

. Also, the Laplace transform is obtainable from the

Fourier transform via analytic continuation. The usefulness of the Laplace

transform relative to the Fourier transform is exactly analogous to that of

the  transform outlined above.

transform outlined above.

Next |

Prev |

Up |

Top

|

Index |

JOS Index |

JOS Pubs |

JOS Home |

Search

[How to cite this work] [Order a printed hardcopy] [Comment on this page via email]

![]() 4.16 is

projected onto another signal

4.16 is

projected onto another signal ![]() using an inner

product. The inner product

using an inner

product. The inner product

![]() computes the coefficient

of projection4.17 of

computes the coefficient

of projection4.17 of ![]() onto

onto ![]() . If

. If

![]() (a sampled, unit-amplitude, zero-phase, complex

sinusoid), then the inner product computes the Discrete Fourier

Transform (DFT), provided the frequencies are chosen to be

(a sampled, unit-amplitude, zero-phase, complex

sinusoid), then the inner product computes the Discrete Fourier

Transform (DFT), provided the frequencies are chosen to be

![]() . For the DFT, the inner product is specifically

. For the DFT, the inner product is specifically

![]() . In this case,

frequency is continuous, and

. In this case,

frequency is continuous, and

![]() (a sampled complex sinusoid with

exponential growth or decay), then the inner product becomes

(a sampled complex sinusoid with

exponential growth or decay), then the inner product becomes

![]() transform when it seems to contain no more information than

the DTFT? It is useful to generalize from the unit circle (where the DFT

and DTFT live) to the entire complex plane (the

transform when it seems to contain no more information than

the DTFT? It is useful to generalize from the unit circle (where the DFT

and DTFT live) to the entire complex plane (the ![]() transform's domain) for

a number of reasons. First, it allows transformation of growing

functions of time such as growing exponentials; the only limitation on

growth is that it cannot be faster than exponential. Secondly, the

transform's domain) for

a number of reasons. First, it allows transformation of growing

functions of time such as growing exponentials; the only limitation on

growth is that it cannot be faster than exponential. Secondly, the ![]() transform has a deeper algebraic structure over the complex plane as a

whole than it does only over the unit circle. For example, the

transform has a deeper algebraic structure over the complex plane as a

whole than it does only over the unit circle. For example, the ![]() transform of any finite signal is simply a polynomial in

transform of any finite signal is simply a polynomial in ![]() . As

such, it can be fully characterized (up to a constant scale factor) by its

zeros in the

. As

such, it can be fully characterized (up to a constant scale factor) by its

zeros in the ![]() plane. Similarly, the

plane. Similarly, the ![]() transform of an

exponential can be characterized to within a scale factor

by a single point in the

transform of an

exponential can be characterized to within a scale factor

by a single point in the ![]() plane (the

point which generates the exponential); since the

plane (the

point which generates the exponential); since the ![]() transform goes

to infinity at that point, it is called a pole of the transform.

More generally, the

transform goes

to infinity at that point, it is called a pole of the transform.

More generally, the ![]() transform of any generalized complex sinusoid

is simply a pole located at the point which generates the sinusoid.

Poles and zeros are used extensively in the analysis of recursive

digital filters. On the most general level, every finite-order, linear,

time-invariant, discrete-time system is fully specified (up to a scale

factor) by its poles and zeros in the

transform of any generalized complex sinusoid

is simply a pole located at the point which generates the sinusoid.

Poles and zeros are used extensively in the analysis of recursive

digital filters. On the most general level, every finite-order, linear,

time-invariant, discrete-time system is fully specified (up to a scale

factor) by its poles and zeros in the ![]() plane. This topic will be taken

up in detail in Book II [71].

plane. This topic will be taken

up in detail in Book II [71].

![]() onto the continuous-time sinusoids defined by

onto the continuous-time sinusoids defined by

![]() , and the appropriate inner product is

, and the appropriate inner product is

![]() transform, and it projects signals onto exponentially growing

or decaying complex sinusoids:

transform, and it projects signals onto exponentially growing

or decaying complex sinusoids: