In this section, we will find the frequency response of the simplest lowpass filter

using simulated sine-wave analysis carried out by a matlab program. This numerical approach complements the analytical approach followed in §1.3. Figure 2.3 gives a listing of the main script which invokes the sine-wave analysis function swanal listed in Fig.

% swanalmain.m - matlab program for simulated sinewave % analysis on the simplest lowpass filter: % % y(n) = x(n)+x(n-1)} B = [1,1]; % filter feedforward coefficients A = 1; % filter feedback coefficients (none) N = 10; % number of sinusoidal test frequencies fs = 1; % sampling rate in Hz (arbitrary) T = 1/fs; % sampling interval in seconds fmax = fs/2; % highest frequency to look at df = fmax/(N-1);% spacing between frequencies f = 0:df:fmax; % sampled frequency axis tmax = 1/df; % 1 cycle at lowest non-dc freq t = 0:T:tmax; % sampled time axis % [gains,phases] = swanal(t,f,fs,B,A); % sinewave analysis swanal; % configured for ease of variable inspection plotfile = '../eps/swanalmain.eps'; swanalmainplot; % final plots and comparison to theory |

In the swanal function (Fig.![]() ), test

sinusoids are generated by the line

), test

sinusoids are generated by the line

s = ampin * cos(2*pi*f(k)*t + phasein);

where amplitude, frequency (Hz), and phase (radians) of the sinusoid are given be

ampin, f(k), and phasein, respectively. As discussed

in §1.3, assuming linearity and time-invariance (LTI) allows

us to set

ampin = 1; % input signal amplitude

phasein = 0; % input signal phase

without loss of generality. (Note that we must also assume the filter

is LTI for sine-wave analysis to be a general method for

characterizing the filter's response.) The test sinusoid is passed

through the digital filter by the line

y = filter(B,A,s); % run s through the filter

producing the output signal in vector y. For this example

(the simplest lowpass filter), the filter coefficients are simply

B = [1,1]; % filter feedforward coefficients

A = 1; % filter feedback coefficients (none)

The coefficient A(1) is technically a coefficient on the

output signal itself, and it should always be normalized to 1.

(B and A can be multiplied by the same nonzero constant to

carry out this normalization when necessary.)

Figure 2.4 shows one of the intermediate plots produced by the

sine-wave analysis routine in Fig.![]() . This figure corresponds

to Fig.1.6 in §1.3 (see page

. This figure corresponds

to Fig.1.6 in §1.3 (see page ![]() ). In

Fig.2.4a, we see samples of the input test sinusoid overlaid

with the continuous sinusoid represented by those

samples. Figure 2.4b shows only the samples of the filter output

signal: While we know the output signal becomes a sampled sinusoid

after the one-sample transient response, we do not know its amplitude

or phase until we measure it; the underlying continuous signal

represented by the samples is therefore not plotted. (If we really

wanted to see this, we could use software for bandlimited

interpolation [91], such as Matlab's

interp function.) A plot such as Fig.2.4 is produced

for each test frequency, and the relative amplitude and phase are

measured between the input and output to form one sample of the

measured frequency response, as discussed in

§1.3.

). In

Fig.2.4a, we see samples of the input test sinusoid overlaid

with the continuous sinusoid represented by those

samples. Figure 2.4b shows only the samples of the filter output

signal: While we know the output signal becomes a sampled sinusoid

after the one-sample transient response, we do not know its amplitude

or phase until we measure it; the underlying continuous signal

represented by the samples is therefore not plotted. (If we really

wanted to see this, we could use software for bandlimited

interpolation [91], such as Matlab's

interp function.) A plot such as Fig.2.4 is produced

for each test frequency, and the relative amplitude and phase are

measured between the input and output to form one sample of the

measured frequency response, as discussed in

§1.3.

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth ]{eps/swanalsix}](img259.png) |

Next, the one-sample start-up transient is removed from the filter

output signal y to form the ``cropped'' signal yss

(``![]() steady state''). The final task is to measure the amplitude

and phase of the yss. Output amplitude estimation is done in

swanal by the line

steady state''). The final task is to measure the amplitude

and phase of the yss. Output amplitude estimation is done in

swanal by the line

[ampout,peakloc] = max(abs(yss));

Note that the peak amplitude found in this way is approximate,

since the true peak of the output sinusoid generally occurs

between samples. We will find the output amplitude much

more accurately in the next two sections. We store the index of the

amplitude peak in peakloc so it can be used to estimate phase

in the next step. Given the output amplitude ampout, the

amplitude response of the filter at frequency f(k) is

given by

gains(k) = ampout/ampin;

The last step of swanal in Fig.

phaseDiff = acos(min(1,max(-1,yss(end)/ampOut))) ...

- acos(min(1,max(-1,sss(end)/ampIn)));

phaseDiff = mod2pi(phaseDiff); % reduce to [-pi,pi)

The mod2pi utility reduces

its scalar argument to the range

function [y] = mod2pi(x) % MOD2PI - Reduce x to the range [-pi,pi) y=x; twopi = 2*pi; while y >= pi, y = y - twopi; end while y < -pi, y = y + twopi; end |

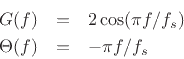

In summary, the sine-wave analysis measures experimentally the gain and phase-shift of the digital filter at selected frequencies, thus measuring the frequency response of the filter at those frequencies. It is interesting to compare these experimental results with the closed-form expressions for the frequency response derived in §1.3.2. From Equations (1.6-1.7) we have

where ![]() denotes the amplitude response (filter gain versus

frequency),

denotes the amplitude response (filter gain versus

frequency), ![]() denotes the phase response (filter

phase-shift versus frequency),

denotes the phase response (filter

phase-shift versus frequency), ![]() is frequency in Hz, and

is frequency in Hz, and ![]() denotes the sampling rate. Both the amplitude response and phase

response are real-valued functions of (real) frequency, while

the frequency response is the complex function of

frequency given by

denotes the sampling rate. Both the amplitude response and phase

response are real-valued functions of (real) frequency, while

the frequency response is the complex function of

frequency given by

![]() .

.

Figure 2.6 shows overlays of the measured and theoretical results. While there is good general agreement, there are noticeable errors in the measured amplitude- and phase-response curves. While we know the input sinusoidal amplitude exactly because we generated it synthetically, the filter output amplitude was crudely approximated as the largest sample magnitude observed, without interpolation to better estimate the true peak amplitude. Phase-response errors are in turn caused by output-amplitude errors.

It is important to understand the source(s) of deviation between the measured and theoretical values. Our simulated sine-wave analysis deviates from an ideal sine-wave analysis in the following ways (listed in ascending order of importance):

The need for interpolation is lessened greatly if the sampling rate is

chosen to be unrelated to the test frequencies (ideally so that the

number of samples in each sinusoidal period is an irrational number).

Figure 2.7 shows the measured and theoretical results obtained

by changing the highest test frequency fmax from ![]() to

to

![]() , and the number of samples in each test sinusoid

tmax from

, and the number of samples in each test sinusoid

tmax from ![]() to

to ![]() . For these parameters, at least one

sample falls very close to a true peak of the output sinusoid at each

test frequency.

. For these parameters, at least one

sample falls very close to a true peak of the output sinusoid at each

test frequency.

It should also be pointed out that one never estimates signal phase in practice by inverting the closed-form functional form assumed for the signal. Instead, we should estimate the delay of each output sinusoid relative to the corresponding input sinusoid. This leads to the general topic of time delay estimation [12]. Under the assumption that the round-off error can be modeled as ``white noise'' (typically this is an accurate assumption), the optimal time-delay estimator is obtained by finding the (interpolated) peak of the cross-correlation between the input and output signals. For further details on cross-correlation, a topic in statistical signal processing, see, e.g., [77,87].

Using the theory presented in later chapters, we will be able to compute very precisely the frequency response of any LTI digital filter without having to resort to bandlimited interpolation (for measuring amplitude response) or time-delay estimation (for measuring phase).