Traveling waves in continuous media are discussed in Appendix G. However, we will summarize the main facts here. While this section is concerned with applying scattering theory to lumped modeling, it is clearest to derive the basic scattering relations in the traveling wave case.

In a traveling wave, force is in phase with velocity. For left-going waves on a string, the minus sign takes care of the fact that a given force (which is proportional to string slope) acts to the left and right with opposite signs. For waves in an acoustic tube, the minus sign properly accounts for longitudinal velocity waves in each direction.

The ratio of force to velocity in a traveling wave, ![]() above, is called

the wave impedance. When the wave impedance changes, from

above, is called

the wave impedance. When the wave impedance changes, from ![]() to

to

![]() , say, scattering occurs at a junction connecting the

two impedances, i.e., the traveling wave splits into reflected and

transmitted components. This follows immediately from the basic

traveling-wave relations above and from physical continuity.

, say, scattering occurs at a junction connecting the

two impedances, i.e., the traveling wave splits into reflected and

transmitted components. This follows immediately from the basic

traveling-wave relations above and from physical continuity.

In vibrating strings, the wave impedance is given by

![]() where

where

![]() is the string tension and

is the string tension and ![]() is mass density. Thus, one way to

change the wave impedance along a stretched string is to change the string

density by adjoining two strings of different material or thickness. It is

more difficult to change the string tension since a ``frictionless vertical

guide rod'' is necessary, in principle. At a junction between two wave

impedances on a string, the physical continuity constraints are that

velocity is unchanged across the junction (to avoid breaking the string)

and the net vertical force at the junction, obtained by summing the force

applied by each string endpoint at the junction, must be zero (to avoid

accelerating a zero mass at the junction). Therefore, the junction is

formally a series connection of the two ports representing the

string endpoints which are joined.

is mass density. Thus, one way to

change the wave impedance along a stretched string is to change the string

density by adjoining two strings of different material or thickness. It is

more difficult to change the string tension since a ``frictionless vertical

guide rod'' is necessary, in principle. At a junction between two wave

impedances on a string, the physical continuity constraints are that

velocity is unchanged across the junction (to avoid breaking the string)

and the net vertical force at the junction, obtained by summing the force

applied by each string endpoint at the junction, must be zero (to avoid

accelerating a zero mass at the junction). Therefore, the junction is

formally a series connection of the two ports representing the

string endpoints which are joined.

In acoustic tubes, the wave impedance is given by ![]() where

where

![]() is the cross-sectional area of the tube (and the velocity variable

is volume velocity). Thus, the easy way to introduce a

scattering junction in an acoustic tube is to change the

cross-sectional area discontinuously. This is why the vocal

tract is modeled as a piecewise cylindrical acoustic tube in speech

modeling [275,82]. At an area discontinuity in an acoustic

tube, the physical continuity constraints are that the pressure must

be continuous across the junction (to avoid accelerating a massless

plane of air at the junction), and the volume velocities (which are

taken as positive when flowing into the junction) must sum to zero at

the junction (so that air particles are not created or destroyed).

Thus, in acoustic tubes, parallel junctions naturally arise

between sections of two different wave impedance.

is the cross-sectional area of the tube (and the velocity variable

is volume velocity). Thus, the easy way to introduce a

scattering junction in an acoustic tube is to change the

cross-sectional area discontinuously. This is why the vocal

tract is modeled as a piecewise cylindrical acoustic tube in speech

modeling [275,82]. At an area discontinuity in an acoustic

tube, the physical continuity constraints are that the pressure must

be continuous across the junction (to avoid accelerating a massless

plane of air at the junction), and the volume velocities (which are

taken as positive when flowing into the junction) must sum to zero at

the junction (so that air particles are not created or destroyed).

Thus, in acoustic tubes, parallel junctions naturally arise

between sections of two different wave impedance.

It is quick to derive the scattering relations for either the ideal string

or acoustic tube. Let

![]() denote the traveling force wave

components immediately to the left of a junction in a string, and let

denote the traveling force wave

components immediately to the left of a junction in a string, and let

![]() denote the components on the right, as shown in

Fig. J.12. Similarly define the velocity wave components. The

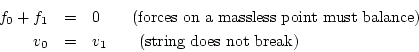

physical continuity constraints can be written

denote the components on the right, as shown in

Fig. J.12. Similarly define the velocity wave components. The

physical continuity constraints can be written

![\includegraphics[scale=0.9]{eps/lstringscat}](img2560.png) |

Let ![]() denote the common velocity of the string endpoints meeting at

a junction. (All velocities are taken as positive in the upward direction.)

Then since

denote the common velocity of the string endpoints meeting at

a junction. (All velocities are taken as positive in the upward direction.)

Then since

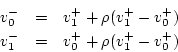

![]() , continuity implies

, continuity implies

![]() .

Therefore, we have

.

Therefore, we have

A scattering diagram is shown in Fig. J.13.

This is the so-called Kelly-Lochbaum form [275]. However, it is important to notice that the scattering equations can also be written

which is diagrammed in Fig. J.14.

Thus, a scattering junction fundamentally requires only one multiplication and three additions.