We have thus far considered discrete-time simulation of transverse

displacement ![]() in the ideal string. It is equally valid to

choose velocity

in the ideal string. It is equally valid to

choose velocity

![]() , acceleration

, acceleration

![]() , slope

, slope ![]() , or perhaps some other derivative

or integral of displacement with respect to time or position.

Conversion between various time derivatives can be carried out by

means integrators and differentiators, as depicted in

Fig. G.10. Since integration and

differentiation are linear operators, and since the traveling

wave arguments are in units of time, the conversion formulas relating

, or perhaps some other derivative

or integral of displacement with respect to time or position.

Conversion between various time derivatives can be carried out by

means integrators and differentiators, as depicted in

Fig. G.10. Since integration and

differentiation are linear operators, and since the traveling

wave arguments are in units of time, the conversion formulas relating

![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() hold also for the traveling wave components

hold also for the traveling wave components

![]() .

.

![\includegraphics[scale=0.9]{eps/fwaveconversions}](img1755.png) |

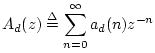

Differentiation and integration have a simple form in the

frequency domain. Denoting the Laplace Transform of ![]() by

by

| (G.35) |

| (G.36) |

In discrete time, integration and differentiation can be accomplished using digital filters [340]. Commonly used first-order approximations are shown in Fig. G.12.

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth]{eps/fdigitaldiffint}](img1760.png) |

If discrete-time acceleration ![]() is defined as the sampled version of

continuous-time acceleration, i.e.,

is defined as the sampled version of

continuous-time acceleration, i.e.,

![]() , (for some fixed continuous position

, (for some fixed continuous position ![]() which we

suppress for simplicity of notation), then the

frequency-domain form is given by the

which we

suppress for simplicity of notation), then the

frequency-domain form is given by the ![]() transform

[462].

transform

[462].

|

(G.37) |

In the frequency domain for discrete-time systems, the first-order approximate conversions appear as shown in Fig. G.13.

![\includegraphics[scale=0.6]{eps/ffddigitaldiffint}](img1764.png) |

The ![]() transform plays the role of the Laplace transform for discrete-time

systems. Setting

transform plays the role of the Laplace transform for discrete-time

systems. Setting ![]() , it can be seen as a sampled Laplace

transform (divided by

, it can be seen as a sampled Laplace

transform (divided by ![]() ), where the sampling is carried out by halting

the limit of the rectangle width at

), where the sampling is carried out by halting

the limit of the rectangle width at ![]() in the definition of a Reimann

integral for the Laplace transform. An important difference between the

two is that the frequency axis in the Laplace transform is the imaginary

axis (the ``

in the definition of a Reimann

integral for the Laplace transform. An important difference between the

two is that the frequency axis in the Laplace transform is the imaginary

axis (the ``![]() axis''), while the frequency axis in the

axis''), while the frequency axis in the ![]() plane is on

the unit circle

plane is on

the unit circle

![]() . As one would expect, the frequency axis for

discrete-time systems has unique information only between frequencies

. As one would expect, the frequency axis for

discrete-time systems has unique information only between frequencies

![]() and

and ![]() while the continuous-time frequency axis extends to plus and

minus infinity.

while the continuous-time frequency axis extends to plus and

minus infinity.

These first-order approximations are accurate (though scaled by ![]() )

at low frequencies relative to half the sampling rate, but they are

not ``best'' approximations in any sense other than being most like

the definitions of integration and differentiation in continuous time.

Much better approximations can be obtained by approaching the problem

from a digital filter design viewpoint [269,323,340]. Arbitrarily better approximations

are possible using higher order digital filters. In principle, a

digital differentiator is a filter whose frequency response

)

at low frequencies relative to half the sampling rate, but they are

not ``best'' approximations in any sense other than being most like

the definitions of integration and differentiation in continuous time.

Much better approximations can be obtained by approaching the problem

from a digital filter design viewpoint [269,323,340]. Arbitrarily better approximations

are possible using higher order digital filters. In principle, a

digital differentiator is a filter whose frequency response

![]() optimally approximates

optimally approximates ![]() for

for ![]() between

between ![]() and

and ![]() . Similarly, a digital

integrator must match

. Similarly, a digital

integrator must match ![]() along the unit circle in the

along the unit circle in the ![]() plane. The reason an exact match is not possible is that the ideal

frequency responses

plane. The reason an exact match is not possible is that the ideal

frequency responses ![]() and

and ![]() , when wrapped along the

unit circle in the

, when wrapped along the

unit circle in the ![]() plane, (the frequency axis for discrete time

systems), are not ``smooth'' functions any more. As a result, there

is no filter with a rational transfer function (i.e., finite order)

that can match the desired frequency response exactly. The frequency

response for the ideal digital differentiator is shown in

Fig. G.14.

plane, (the frequency axis for discrete time

systems), are not ``smooth'' functions any more. As a result, there

is no filter with a rational transfer function (i.e., finite order)

that can match the desired frequency response exactly. The frequency

response for the ideal digital differentiator is shown in

Fig. G.14.

![\includegraphics[scale=0.9]{eps/f_ideal_diff_fr}](img1770.png) |

The discontinuity at ![]() alone is enough to ensure that no

finite-order digital transfer function exists with the desired frequency

response. As with bandlimited interpolation, it is good practice to

reserve the top 10-20% of the spectrum as a ``guard band,'' above the

limits of human hearing, where digital filters are free to smoothly vary in

whatever way gives the best performance across frequencies in the audible

band at the lowest cost. Note that, as in filters used for bandlimited

interpolation, a small increment in oversampling factor yields a much

larger decrease in filter cost when the sampling rate is low.

alone is enough to ensure that no

finite-order digital transfer function exists with the desired frequency

response. As with bandlimited interpolation, it is good practice to

reserve the top 10-20% of the spectrum as a ``guard band,'' above the

limits of human hearing, where digital filters are free to smoothly vary in

whatever way gives the best performance across frequencies in the audible

band at the lowest cost. Note that, as in filters used for bandlimited

interpolation, a small increment in oversampling factor yields a much

larger decrease in filter cost when the sampling rate is low.

In the general case, digital filters can be designed to give arbitrarily

accurate differentiation and integration by finding an optimal, complex,

rational approximation to

![]() over the interval

over the interval

![]() , where

, where ![]() is an integer corresponding to

the degree of differentiation or integration, and

is an integer corresponding to

the degree of differentiation or integration, and

![]() is the upper

limit of human hearing. For small guard bands

is the upper

limit of human hearing. For small guard bands

![]() , the filter order required for a given error tolerance is

approximately inversely proportional to

, the filter order required for a given error tolerance is

approximately inversely proportional to ![]() [340,323,166,34].

[340,323,166,34].