Next |

Prev |

Up |

Top

|

Index |

JOS Index |

JOS Pubs |

JOS Home |

Search

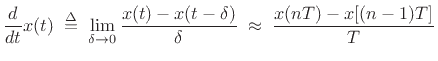

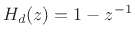

Recall that the Finite Difference Approximation (FDA) defines the

elementary differentiator by

(ignoring the

scale factor

(ignoring the

scale factor  for now), and this approximates the ideal transfer

function

for now), and this approximates the ideal transfer

function  by

by

. The bilinear transform

calls instead for the transfer function

. The bilinear transform

calls instead for the transfer function

(again

dropping the scale factor) which introduces a pole at

(again

dropping the scale factor) which introduces a pole at  and gives

us the recursion

and gives

us the recursion

.

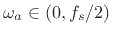

Note that this new pole is right on the unit circle and is therefore

undamped. Any signal energy at half the sampling rate will circulate

forever in the recursion, and due to round-off error, it will tend to

grow. This is therefore a potentially problematic revision of the

differentiator. To get something more practical, we need to specify

that the filter frequency response approximate

.

Note that this new pole is right on the unit circle and is therefore

undamped. Any signal energy at half the sampling rate will circulate

forever in the recursion, and due to round-off error, it will tend to

grow. This is therefore a potentially problematic revision of the

differentiator. To get something more practical, we need to specify

that the filter frequency response approximate

over a

finite range of frequencies

over a

finite range of frequencies

![$ [-\omega_c,\omega_c]$](img1679.png) , where

, where

, above which we allow the response to ``roll off''

to zero. This is how we pose the differentiator problem in terms of

general purpose filter design (see §8.6) [365].

, above which we allow the response to ``roll off''

to zero. This is how we pose the differentiator problem in terms of

general purpose filter design (see §8.6) [365].

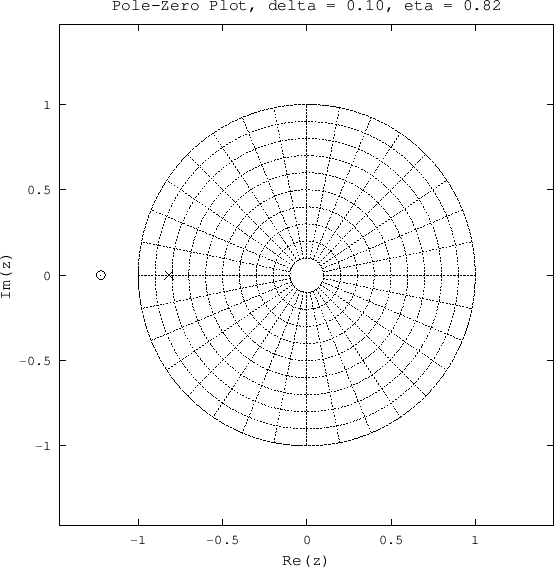

To understand the properties of the finite difference approximation in the

frequency domain, we may look at the properties of its  -plane

to

-plane

to  -plane mapping

-plane mapping

We see the FDA is actually a portion of the bilinear transform, since

following the FDA mapping by the mapping

would convert it

to the bilinear transform. Like the bilinear transform, the FDA does not

alias, since the mapping

would convert it

to the bilinear transform. Like the bilinear transform, the FDA does not

alias, since the mapping

is one-to-one.

is one-to-one.

Setting  to 1 for simplicity and solving the FDA mapping for z gives

to 1 for simplicity and solving the FDA mapping for z gives

We see that analog dc ( ) maps to digital dc (

) maps to digital dc ( ) as desired,

but higher frequencies unfortunately map inside the unit circle rather

than onto the unit circle in the

) as desired,

but higher frequencies unfortunately map inside the unit circle rather

than onto the unit circle in the  plane.

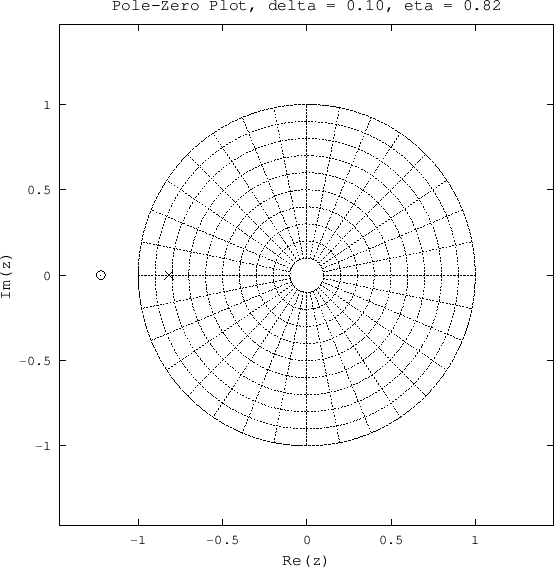

Solving for the image in the z plane of the

plane.

Solving for the image in the z plane of the  axis in the s plane gives

axis in the s plane gives

From this it can be checked that the FDA maps the  axis in the

axis in the  plane to the circle of radius

plane to the circle of radius  centered at the point

centered at the point  in the

in the

plane, as shown in Fig. 7.15

plane, as shown in Fig. 7.15

Figure 7.15:

Image of the  axis in the

axis in the  plane: a circle of radius

plane: a circle of radius  centered at the point

centered at the point  .

.

![\includegraphics[width=3in]{eps/lfdacirc}](img1686.png) |

Under the FDA, analog and digital frequency axes coincide well enough at

very low frequencies (high sampling rates), but at high frequencies

relative to the sampling rate, artificial damping is introduced as

the image of the  axis diverges away from the unit circle.

axis diverges away from the unit circle.

While the bilinear transform ``warps'' the frequency axis, we can say the

FDA ``doubly warps'' the frequency axis: It has a progressive, compressive

warping in the direction of increasing frequency, like the bilinear

transform, but unlike the bilinear transform, it also warps normal

to the frequency axis.

Consider a point traversing the upper half of the unit circle in the z

plane, starting at  and ending at

and ending at  . At dc, the FDA is

perfect, but as we proceed out along the unit circle, we diverge from the

. At dc, the FDA is

perfect, but as we proceed out along the unit circle, we diverge from the

axis image and carve an arc somewhere out in the image of the

right-half

axis image and carve an arc somewhere out in the image of the

right-half  plane. This has the effect of introducing an artificial

damping.

plane. This has the effect of introducing an artificial

damping.

Consider, for example, an undamped mass-spring system. There will be a

complex conjugate pair of poles on the  axis in the

axis in the  plane. After

the FDA, those poles will be inside the unit circle, and therefore damped

in the digital counterpart. The higher the resonance frequency, the larger

the damping. It is even possible for unstable

plane. After

the FDA, those poles will be inside the unit circle, and therefore damped

in the digital counterpart. The higher the resonance frequency, the larger

the damping. It is even possible for unstable  -plane poles to be mapped

to stable

-plane poles to be mapped

to stable  -plane poles.

-plane poles.

In summary, both the bilinear transform and the FDA preserve order,

stability, and positive realness. They are both free of aliasing, high

frequencies are compressively warped, and both become ideal at dc, or as

approaches

approaches  . However, at frequencies significantly above

zero relative to the sampling rate, only the FDA introduces artificial

damping. The bilinear transform maps the continuous-time frequency axis in

the

. However, at frequencies significantly above

zero relative to the sampling rate, only the FDA introduces artificial

damping. The bilinear transform maps the continuous-time frequency axis in

the  (the

(the  axis) plane precisely to the discrete-time frequency

axis in the

axis) plane precisely to the discrete-time frequency

axis in the  plane (the unit circle).

plane (the unit circle).

Next |

Prev |

Up |

Top

|

Index |

JOS Index |

JOS Pubs |

JOS Home |

Search

[How to cite this work] [Order a printed hardcopy] [Comment on this page via email]

![]() (ignoring the

scale factor

(ignoring the

scale factor ![]() for now), and this approximates the ideal transfer

function

for now), and this approximates the ideal transfer

function ![]() by

by

![]() . The bilinear transform

calls instead for the transfer function

. The bilinear transform

calls instead for the transfer function

![]() (again

dropping the scale factor) which introduces a pole at

(again

dropping the scale factor) which introduces a pole at ![]() and gives

us the recursion

and gives

us the recursion

![]() .

Note that this new pole is right on the unit circle and is therefore

undamped. Any signal energy at half the sampling rate will circulate

forever in the recursion, and due to round-off error, it will tend to

grow. This is therefore a potentially problematic revision of the

differentiator. To get something more practical, we need to specify

that the filter frequency response approximate

.

Note that this new pole is right on the unit circle and is therefore

undamped. Any signal energy at half the sampling rate will circulate

forever in the recursion, and due to round-off error, it will tend to

grow. This is therefore a potentially problematic revision of the

differentiator. To get something more practical, we need to specify

that the filter frequency response approximate

![]() over a

finite range of frequencies

over a

finite range of frequencies

![]() , where

, where

![]() , above which we allow the response to ``roll off''

to zero. This is how we pose the differentiator problem in terms of

general purpose filter design (see §8.6) [365].

, above which we allow the response to ``roll off''

to zero. This is how we pose the differentiator problem in terms of

general purpose filter design (see §8.6) [365].

![]() -plane

to

-plane

to ![]() -plane mapping

-plane mapping

![]() to 1 for simplicity and solving the FDA mapping for z gives

to 1 for simplicity and solving the FDA mapping for z gives

![]() axis diverges away from the unit circle.

axis diverges away from the unit circle.

![]() and ending at

and ending at ![]() . At dc, the FDA is

perfect, but as we proceed out along the unit circle, we diverge from the

. At dc, the FDA is

perfect, but as we proceed out along the unit circle, we diverge from the

![]() axis image and carve an arc somewhere out in the image of the

right-half

axis image and carve an arc somewhere out in the image of the

right-half ![]() plane. This has the effect of introducing an artificial

damping.

plane. This has the effect of introducing an artificial

damping.

![]() axis in the

axis in the ![]() plane. After

the FDA, those poles will be inside the unit circle, and therefore damped

in the digital counterpart. The higher the resonance frequency, the larger

the damping. It is even possible for unstable

plane. After

the FDA, those poles will be inside the unit circle, and therefore damped

in the digital counterpart. The higher the resonance frequency, the larger

the damping. It is even possible for unstable ![]() -plane poles to be mapped

to stable

-plane poles to be mapped

to stable ![]() -plane poles.

-plane poles.

![]() approaches

approaches ![]() . However, at frequencies significantly above

zero relative to the sampling rate, only the FDA introduces artificial

damping. The bilinear transform maps the continuous-time frequency axis in

the

. However, at frequencies significantly above

zero relative to the sampling rate, only the FDA introduces artificial

damping. The bilinear transform maps the continuous-time frequency axis in

the ![]() (the

(the ![]() axis) plane precisely to the discrete-time frequency

axis in the

axis) plane precisely to the discrete-time frequency

axis in the ![]() plane (the unit circle).

plane (the unit circle).