We will now derive the convolution representation for causal LTI filters

in its full generality. The first step is to express an arbitrary signal

![]() as a linear combination of shifted impulses, i.e.,

as a linear combination of shifted impulses, i.e.,

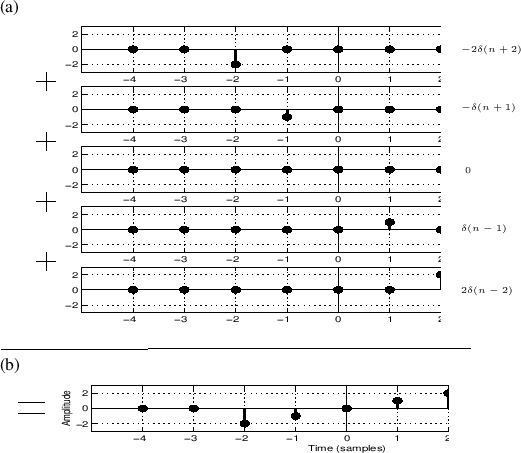

If the above equation is not obvious, here is how it is built up

intuitively. Imagine

![]() as a 1 in the midst of an

infinite string of 0s. Now think of

as a 1 in the midst of an

infinite string of 0s. Now think of

![]() as the same

pattern shifted over to the right by

as the same

pattern shifted over to the right by ![]() samples. Next multiply

samples. Next multiply

![]() by

by ![]() , which plucks out the sample

, which plucks out the sample ![]() and surrounds it on both sides by 0's. An example collection of

waveforms

and surrounds it on both sides by 0's. An example collection of

waveforms

![]() for the case

for the case

![]() is shown in

Fig.5.4a. Now, sum over all

is shown in

Fig.5.4a. Now, sum over all ![]() , bringing together the

samples of

, bringing together the

samples of ![]() , to obtain

, to obtain ![]() . Figure 5.4b

shows the result of this addition for the sequences in

Fig.5.4a. Thus, any signal

. Figure 5.4b

shows the result of this addition for the sequences in

Fig.5.4a. Thus, any signal ![]() may be expressed as a

weighted sum of shifted impulses.

may be expressed as a

weighted sum of shifted impulses.

Equation (5.4) expresses a signal as a linear combination (or weighted sum) of impulses. That is, each sample may be viewed as an impulse at some amplitude and time. As we have already seen, each impulse (sample) arriving at the filter's input will cause the filter to produce an impulse response. If another impulse arrives at the filter's input before the first impulse response has died away, then the impulse response for both impulses will superimpose (add together sample by sample). More generally, since the input is a linear combination of impulses, the output is the same linear combination of impulse responses. This is a direct consequence of the superposition principle which holds for any LTI filter.

|

We repeat this in more precise terms. First linearity is used and then time-invariance is invoked. Using the form of the general linear filter in Eq.(4.2), and the definition of linearity, Eq.(4.3) and Eq.(4.5), we can express the output of any linear (and possibly time-varying) filter by

where we have written

to denote the filter

response at time

to denote the filter

response at time ![]() to an impulse which occurred at time

to an impulse which occurred at time ![]() . If we are

to be completely rigorous mathematically, certain ``smoothness''

restrictions must be placed on the linear operator

. If we are

to be completely rigorous mathematically, certain ``smoothness''

restrictions must be placed on the linear operator ![]() in order that

it may be distributed inside the infinite summation [37].

However, practically useful filters of the

form of Eq.(5.1) satisfy these restrictions. If in addition to

being linear, the filter is time-invariant, then

in order that

it may be distributed inside the infinite summation [37].

However, practically useful filters of the

form of Eq.(5.1) satisfy these restrictions. If in addition to

being linear, the filter is time-invariant, then

![]() ,

which allows us to write

,

which allows us to write

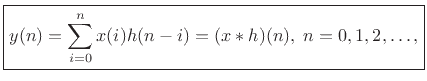

The infinite sum

in Eq.(5.5) can be replaced by more typical practical

limits. By choosing time 0 as the beginning of the signal, we may

define ![]() to be 0 for

to be 0 for ![]() so that the lower summation limit of

so that the lower summation limit of

![]() can be replaced by 0. Also, if the filter is causal, we

have

can be replaced by 0. Also, if the filter is causal, we

have ![]() for

for ![]() , so the upper summation limit can be

written as

, so the upper summation limit can be

written as ![]() instead of

instead of ![]() . Thus, the

convolution representation of a linear, time-invariant, causal

digital filter is given by

. Thus, the

convolution representation of a linear, time-invariant, causal

digital filter is given by

for causal input signals (i.e.,

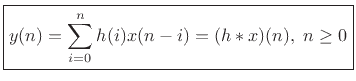

Since the above equation is a convolution, and since convolution is

commutative (i.e.,

![]() [84]), we

can rewrite it as

[84]), we

can rewrite it as

or

This latter form looks more like the general difference equation presented in Eq.(5.1). In this form one can see that