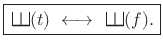

The impulse signal ![]() (defined in §B.10)

has a constant Fourier transform:

(defined in §B.10)

has a constant Fourier transform:

|

(B.43) |

|

(B.44) |

|

(B.46) |

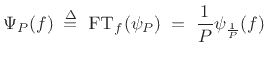

We will now show that

|

(B.47) |

|

(B.48) |

Thus, the ![]() -periodic impulse train transforms to a

-periodic impulse train transforms to a ![]() -periodic

impulse train, in which each impulse contains area

-periodic

impulse train, in which each impulse contains area ![]() :

:

|

(B.49) |

Proof:

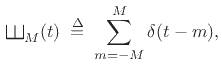

Let's set up a limiting construction by defining

|

(B.50) |

![\begin{eqnarray*}

\hbox{\sc FT}_f(\,\raisebox{0.8em}{\rotatebox{-90}{\resizebox{1em}{1em}{\ensuremath{\exists}}}}_M) &\isdef & \hbox{\sc FT}_f\left[\sum_{m=-M}^M \hbox{\sc Shift}_{m}(\delta)\right]\\

&=& \sum_{m=-M}^M \hbox{\sc FT}_f[\hbox{\sc Shift}_{m}(\delta)] \eqsp \sum_{m=-M}^M e^{-j2\pi f m}.

\end{eqnarray*}](img2497.png)

Using the closed form of a geometric series,

|

(B.51) |

![\begin{eqnarray*}

\hbox{\sc FT}_f(\,\raisebox{0.8em}{\rotatebox{-90}{\resizebox{1em}{1em}{\ensuremath{\exists}}}}_M)

&=& \frac{e^{j2\pi f M } - e^{-j2\pi f M } e^{-j2\pi f }}{1-e^{-j2\pi f }}\\ [10pt]

&=& \frac{e^{-j\pi f}}{e^{-j\pi f}}

\cdot

\frac{e^{j\pi f (2M+1) } - e^{-j\pi f (2M+1) }}{e^{j\pi f}-e^{-j\pi f}}\\ [10pt]

&=& \frac{\sin[\pi f (2M+1) ]}{\sin(\pi f)}\\ [5pt]

&\isdef & (2M+1)\,\hbox{asinc}_{2M+1}(2\pi f )

\end{eqnarray*}](img2500.png)

where we have used the definition of

![]() given in

Eq.(3.5) of §3.1. As we would

expect from basic sampling theory, the Fourier transform of the

sampled rectangular pulse is an aliased sinc function.

Figure 3.2 illustrates one period

given in

Eq.(3.5) of §3.1. As we would

expect from basic sampling theory, the Fourier transform of the

sampled rectangular pulse is an aliased sinc function.

Figure 3.2 illustrates one period

![]() for

for

![]() .

.

The proof can be completed by expressing the aliased sinc function as

a sum of regular sinc functions, and using linearity of the Fourier

transform to distribute

![]() over the sum, converting each sinc

function into an impulse, in the limit, by §B.13:

over the sum, converting each sinc

function into an impulse, in the limit, by §B.13:

![\begin{eqnarray*}

(2M+1)\,\hbox{asinc}_{2M+1}(2\pi f) &\isdef &

\frac{\sin[\pi f (2M+1) ]}{\sin(\pi f)}\\ [5pt]

&=& \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} \mbox{sinc}(2Mf-k)\\ [5pt]

&\to& \sum_{k=-\infty}^{\infty} \delta(f-k)

\end{eqnarray*}](img2503.png)

by §B.13.

Note that near

![]() , we have

, we have

![\begin{eqnarray*}

\hbox{\sc FT}_f(\,\raisebox{0.8em}{\rotatebox{-90}{\resizebox{1em}{1em}{\ensuremath{\exists}}}}_M) &=& \frac{\sin[\pi f (2M+1) ]}{\sin(\pi f)}

\;\;\approx\;\; \frac{\sin[\pi f (2M+1) ]}{\pi f}\\ [5pt]

&=&(2M+1)\mbox{sinc}[(2M+1)f]

\;\;\to\;\;\delta(f)

\end{eqnarray*}](img2505.png)

as

![]() , as shown in §B.13. Similarly, near

, as shown in §B.13. Similarly, near

![]() , we have

, we have

![$\displaystyle \hbox{\sc FT}_f(\,\raisebox{0.8em}{\rotatebox{-90}{\resizebox{1em}{1em}{\ensuremath{\exists}}}}_M) \;\;\approx\;\; \frac{\sin[\pi f (2M+1) ]}{-\pi f} \;\;\to\;\;\delta(f)$](img2508.png) |

(B.52) |

|

(B.53) |

See, e.g., [23,79] for more about impulses and their application in Fourier analysis and linear systems theory.

Exercise: Using a similar limiting construction as before,

|

(B.54) |

show that a direct inverse-Fourier transform calculation gives

![$\displaystyle \psi_{P,L}(t) = \frac{\sin\left[\pi(2L+1)\frac{t}{P}\right]}{\sin\left( \pi \frac{t}{P}\right)},$](img2512.png) |

(B.55) |

and verify that the peaks occur everyseconds and reach height

. Also show that the peak widths, measured between zero crossings, are

, so that the area under each peak is of order 1 in the limit as

. [Hint: The shift theorem for inverse Fourier transforms is

, and

.]