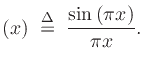

Perhaps the most obviously ideal sampling kernel ![]() for a

speaker centered at

for a

speaker centered at ![]() within a line-array with cell-width

within a line-array with cell-width ![]() is

the rectangular pulse:

is

the rectangular pulse:

![$\displaystyle g_y(x) = \left\{\begin{array}{ll}

\frac{1}{X}, & \vert x\vert<\frac{X}{2} \\ [5pt]

0, & \mbox{otherwise} \\

\end{array} \right.

$](img147.png)

That is, each speaker in the array pushes a unit volume of air in one second (unit area). Such a speaker array can be regarded as a series of contiguous pistons, each of width

The unit-area pulse function is not bandlimited. A more graceful choice is the ``spatial sinc function,'' which is the ideal sampling kernel used in bandlimited audio sampling:

where

It is well known that the sinc function is the Fourier transform of a rectangular pulse, and vice versa. Therefore, rectangular-pulse samples at the line array propagate and diffract to become overlapping sinc functions in the far field, while sinc-shaped radiation patterns diffract to become adjacent or overlapping rectangular spatial bands in the far field. Of course, a true sinc function can never be implemented precisely because it is infinite in spatial extent. Still, it is interesting to imagine disjoint spatial samples in the far field, and consider whether approaching that might be desirable in some situations, such as delivering different program material to different listening positions (a current problem in automotive sound).

The most typical example in practice is a circular driver--an

ordinary circular speaker cone. In this case, the far field shape is

the so-called ``Airy function'' involving Bessel function

![]() .22

.22

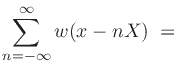

In addition to the rectangular piston and sinc function, or circular

driver and Airy pattern, any spectrum-analysis window ![]() , or its

Fourier transform

, or its

Fourier transform ![]() , having the constant-overlap-add (COLA)

property

, having the constant-overlap-add (COLA)

property

constant

constant

can be used as a spatial sampling kernel, with the added stipulation that

Spatial oversampling gives more flexibility in the choice of radiation pattern. For example, doubling the spatial sampling rate allows the radiation patterns to overlap by an additional factor of two with no loss of spatial resolution along the line array. On the other hand, that factor of two could be given to the aliasing cutoff frequency, which is probably a better use of it.

As in audio interpolation, windowed sinc interpolation can be used in practice (Smith and Gossett, 1984), if a speaker driver can be devised to generate that radiation pattern at some distance from the speaker.

The spatial sampling kernel should ideally be frequency independent, but this is never the case for typical speaker systems. Instead, typical speakers look like point sources at low frequencies, radiate efficiently and widely at wavelengths comparable to the speaker diameter, and begin to ``spotlight'' increasingly at higher frequencies (where the diameter is multiple wavelengths).

Due to the naturally narrowing spatial beam-width with increasing frequency for typical speaker drivers, a sufficient sampling density for high frequencies corresponds to heavy oversampling (spatially) at low frequencies. PBAP and its extensions therefore should either be implemented in separate frequency bands (multiband PBAP is discussed below), or using a new kind of speaker having a frequency-independent radiation pattern that sums to a constant when the speaker outputs are all added together at any point of the listening region. One solution is to approximate a point source (see Appendix B), for which the sampling kernel is a substantially identical sphere for all speaker drivers much smaller than a wavelength. Such speakers radiate inefficiently, but they are already widely used at the low-frequency end in practice (subwoofers are smaller than most of the wavelengths they must produce). The main problem with a single set of point-source-approximation drivers is that they must be packed very densely for the high frequencies and also have long-throw excursion for low frequencies--expensive. Furthermore, there is always intermodulation distortion in any wideband driver (e.g., Doppler shift of high-frequency components by low-frequency excursion, which nobody apparently compensates).

http://arxiv.org/abs/1911.07575.