Next |

Prev |

Up |

Top

|

Index |

JOS Index |

JOS Pubs |

JOS Home |

Search

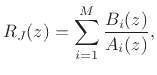

As noted in [25] et al., it is natural in

practice to implement the junction load impedance (or admittance) as

bank of parallel biquads:

|

(C.102) |

where  is the number of biquads, and we define

is the number of biquads, and we define

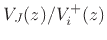

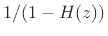

A hasty implementation of Eq.(C.97) might overlook

the fact that all junction transfer-functions (transmittances,

reflectances, etc.) must have the same poles (or some subset of

them). It is therefore typical to share the pole computations

among all junction transfer functions, that is, implement the

recursive part only once, and form all desired junction transfer

functions as linear combinations of the same state variables (or

biquad sections, etc.). Thus, only the numerators differ

between transmittances

and reflectances

and reflectances

, for example. The ``dynamics'' are shared because

there is only one physical system being modeled, but the inputs and

outputs vary, yielding different zeros.

, for example. The ``dynamics'' are shared because

there is only one physical system being modeled, but the inputs and

outputs vary, yielding different zeros.

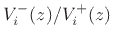

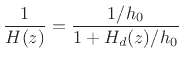

A basic trick for implementing the reciprocal of a transfer

function without altering its denominator(s) is to place it in

a feedback loop. If

denotes the starting

transfer function, then placing it in a feedback loop gives

denotes the starting

transfer function, then placing it in a feedback loop gives

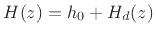

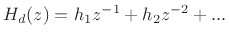

. Now split

. Now split  into its instantaneous and delayed

components

into its instantaneous and delayed

components

, where

, where

. If

. If  (otherwise pull out unit-sample delays until it is),

then we can realize

(otherwise pull out unit-sample delays until it is),

then we can realize  as

as

|

(C.105) |

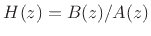

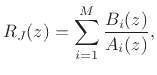

which can be implemented as a feedback loop containing

as the feedback filter, and the scale factor

as the feedback filter, and the scale factor  in the forward path, as shown in Fig.C.30.

In the case of a parallel biquad realization, structure is preserved

with altered numerators obtained by extracting the instantaneous gain

from each section, as we'll see the following examples.

in the forward path, as shown in Fig.C.30.

In the case of a parallel biquad realization, structure is preserved

with altered numerators obtained by extracting the instantaneous gain

from each section, as we'll see the following examples.

Figure C.30:

Feedback arrangement for inverting the filter

while preserving

parallel-biquads structure.

while preserving

parallel-biquads structure.

![\includegraphics[width=0.6\twidth]{eps/InvertFilter}](img3985.png) |

Subsections

Next |

Prev |

Up |

Top

|

Index |

JOS Index |

JOS Pubs |

JOS Home |

Search

[How to cite this work] [Order a printed hardcopy] [Comment on this page via email]

![]() denotes the starting

transfer function, then placing it in a feedback loop gives

denotes the starting

transfer function, then placing it in a feedback loop gives

![]() . Now split

. Now split ![]() into its instantaneous and delayed

components

into its instantaneous and delayed

components

![]() , where

, where

![]() . If

. If ![]() (otherwise pull out unit-sample delays until it is),

then we can realize

(otherwise pull out unit-sample delays until it is),

then we can realize ![]() as

as

![\includegraphics[width=0.6\twidth]{eps/InvertFilter}](img3985.png)