|

(G.1) |

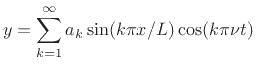

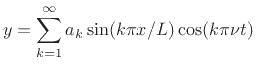

The history of spectral modeling of sound arguably begins with Daniel Bernoulli, who first believed (in the 1733-1742 time frame) that any acoustic vibration could be expressed as a superposition of ``simple modes'' (sinusoidal vibrations) [52].G.1Bernoulli was able to show this precisely for the case of identical masses interconnected by springs to form a discrete approximation to an ideal string. Leonard Euler first wrote down (1749) a mathematical expression of Bernoulli's insight for a special case of the continuous vibrating string:

|

(G.1) |

Note that organ builders had already for centuries built machines for performing a kind of ``additive synthesis'' by gating various ranks of pipes using ``stops'' as in pipe organs found today. However, the waveforms mixed together were not sinusoids, and were not regarded as mixtures of sinusoids. Theories of sound at that time, based on the ideas of Galileo, Mersenne, and Sauveur, et al. [52], were based on time-domain pulse-train analysis. That is, an elementary tone at a fixed pitch (and fundamental frequency) was a periodic pulse train, with the pulse-shape being non-critical. Musical consonance was associated with pulse-train coincidence--not frequency-domain separation. Bernoulli clearly suspected the spectrum analysis function integral to hearing as well as color perception [52, p. 359], but the concept of the ear as a spectrum analyzer is generally attributed to Helmholtz (1863) [293].