From Eq.(E.11), it is clear that initializing any single K variable

![]() corresponds to the initialization of an infinite number of W

variables

corresponds to the initialization of an infinite number of W

variables

![]() and

and

![]() . That is, a single K variable

. That is, a single K variable ![]() corresponds to only a single column of

corresponds to only a single column of

![]() for only one of the

interleaved grids. For example,

referring to Eq.(E.11),

initializing the K variable

for only one of the

interleaved grids. For example,

referring to Eq.(E.11),

initializing the K variable

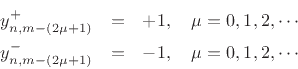

![]() to -1 at time

to -1 at time ![]() (with all other

(with all other ![]() intialized to 0)

corresponds to the W-variable initialization

intialized to 0)

corresponds to the W-variable initialization

with all other W variables being initialized to zero.

In view of earlier remarks, this corresponds to an impulsive velocity

excitation on only one of the two subgrids. A schematic

depiction from ![]() to

to ![]() of the W variables at time

of the W variables at time ![]() is as

follows:

is as

follows:

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{array}{crrrrr\vert rrrrrrc} \cdots & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ \cdots & -1 & 0 & -1 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ \hline\\ [-1em] \cdots & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ & & & & & & m & & & & & \mu & \rightarrow \end{array}\end{displaymath}](img4640.png) |

(E.14) |

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{array}{crrrrr\vert rrrrrrc} \cdots & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ \cdots & 0 & -1 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ \hline\\ [-1em] \cdots & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots \end{array}\end{displaymath}](img4644.png) |

(E.15) |

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{array}{crrrrr\vert rrrrrrc} \cdots & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ \cdots & -1 & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ \hline\\ [-1em] \cdots & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots \end{array}\end{displaymath}](img4645.png) |

(E.16) |

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{array}{crrrrr\vert rrrrrrc} \cdots & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ \cdots & 0 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ \hline\\ [-1em] \cdots & 0 & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots \end{array}\end{displaymath}](img4646.png) |

(E.17) |

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{array}{crrrrr\vert rrrrrrc} \cdots & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ \cdots & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ \hline\\ [-1em] \cdots & 0 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 1 & 0 & 0 & \cdots \end{array}\end{displaymath}](img4647.png) |

(E.18) |

Due to the independent interleaved subgrids in the FDTD algorithm, it is nearly always non-physical to excite only one of them, as the above example makes clear. It is analogous to illuminating only every other pixel in a digital image. However, joint excitation of both grids may be accomplished either by exciting adjacent spatial samples at the same time, or the same spatial sample at successive times instants.

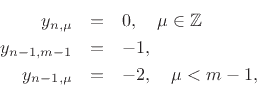

In addition to the W components being non-local, they can demand a

larger dynamic range than the K variables. For example, if the entire

semi-infinite string for ![]() is initialized with velocity

is initialized with velocity ![]() ,

the initial displacement traveling-wave components look as follows:

,

the initial displacement traveling-wave components look as follows:

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{array}{crrrrrr\vert rrrrrc} \cdots & 6 & 5 & 4 & 3 & 2 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ \cdots & -6 & -5 & -4 & -3 & -2 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ \hline\\ [-1em] \cdots & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots \end{array}\end{displaymath}](img4651.png) |

(E.19) |

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{array}{crrrrrr\vert rrrrrc} \cdots & 7 & 6 & 5 & 4 & 3 & 2 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ \cdots & -5 & -4 & -3 & -2 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ \hline\\ [-1em] \cdots & 2 & 2 & 2 & 2 & 2 & 2 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots \end{array}\end{displaymath}](img4652.png) |

(E.20) |

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{array}{crrrrrr\vert rrrrrc} \cdots & 8 & 7 & 6 & 5 & 4 & 3 & 2 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ \cdots & -4 & -3 & -2 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ \hline\\ [-1em] \cdots & 4 & 4 & 4 & 4 & 4 & 3 & 2 & 1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots \end{array}\end{displaymath}](img4653.png) |

(E.21) |

![\begin{displaymath}\begin{array}{crrrrrr\vert rrrrrc} \cdots & 9 & 8 & 7 & 6 & 5 & 4 & 3 & 2 & 1 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ \cdots & -3 & -2 & -1 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & 0 & \cdots\\ \hline\\ [-1em] \cdots & 6 & 6 & 6 & 6 & 5 & 4 & 3 & 2 & 1 & 0 & 0 & \cdots \end{array}\end{displaymath}](img4654.png) |

(E.22) |

where

![]() denotes the set of all integers.

While the FDTD excitation is also not local, of course, it is

bounded for all

denotes the set of all integers.

While the FDTD excitation is also not local, of course, it is

bounded for all ![]() .

.

Since the traveling-wave components of initial velocity excitations are generally non-local in a displacement-based simulation, as illustrated in the preceding examples, it is often preferable to use velocity waves (or force waves) in the first place [450].

Another reason to prefer force or velocity waves is that displacement

inputs are inherently impulsive. To see why this is so, consider that

any physically correct driving input must effectively exert some

finite force on the string, and this force is free to change

arbitrarily over time. The ``equivalent circuit'' of the infinitely

long string at the driving point is a ``dashpot'' having real,

positive resistance

![]() . The applied force

. The applied force ![]() can be

divided by

can be

divided by ![]() to obtain the velocity

to obtain the velocity ![]() of the string driving

point, and this velocity is free to vary arbitrarily over time,

proportional to the applied force. However, this velocity must be

time-integrated to obtain a displacement

of the string driving

point, and this velocity is free to vary arbitrarily over time,

proportional to the applied force. However, this velocity must be

time-integrated to obtain a displacement ![]() . Therefore,

there can be no instantaneous displacement response to a finite

driving force. In other words, any instantaneous effect of an input

driving signal on an output displacement sample is non-physical except

in the case of a massless system. Infinite force is required to move

the string instantaneously. In sampled displacement simulations, we

must interpret displacement changes as resulting from time-integration

over a sampling period. As the sampling rate increases, any

physically meaningful displacement driving signal must converge to

zero.

. Therefore,

there can be no instantaneous displacement response to a finite

driving force. In other words, any instantaneous effect of an input

driving signal on an output displacement sample is non-physical except

in the case of a massless system. Infinite force is required to move

the string instantaneously. In sampled displacement simulations, we

must interpret displacement changes as resulting from time-integration

over a sampling period. As the sampling rate increases, any

physically meaningful displacement driving signal must converge to

zero.