In Defense of Cheap Tools

Arful Design Chapter 4

I am responding to Ge Wang's Artful Design, Chapter 4.

The Max Mathews quote about finding the "good" sounds computers can generate

(Wang 166) reminded me of something my first electroacoustic composition

teacher, Joo Won Park, once said:

"Not all interesting music is pleasurable to listen to, and not all

pleasurable music is interesting" (paraphrasing). I imagine computer music

as a plane with two axes, one representing newness and the other pleasantness.

New in this context means explorating the far reaches of what technology and

composition have to offer, rather than not sounding hackneyed. Did "good" to

Max Mathews mean pleasant or interesting? I'd like to think he meant both.

In my composition practice, I've often been self-conscious of

not being very far along the axis of newness. I like to use acoustic sources,

strong harmonic centers, and looping structures. On the other hand, I know

my pieces can be "easier" listening than some others in my field. As my

interest in the accessibility of electroacoustic music and music technology

has deepened, I've begun to see its relationship to my pre-existing composing

tendencies. It's not laziness or uncreativity to create points of familiarity

in the midst of less familiar song structures or sound sources.

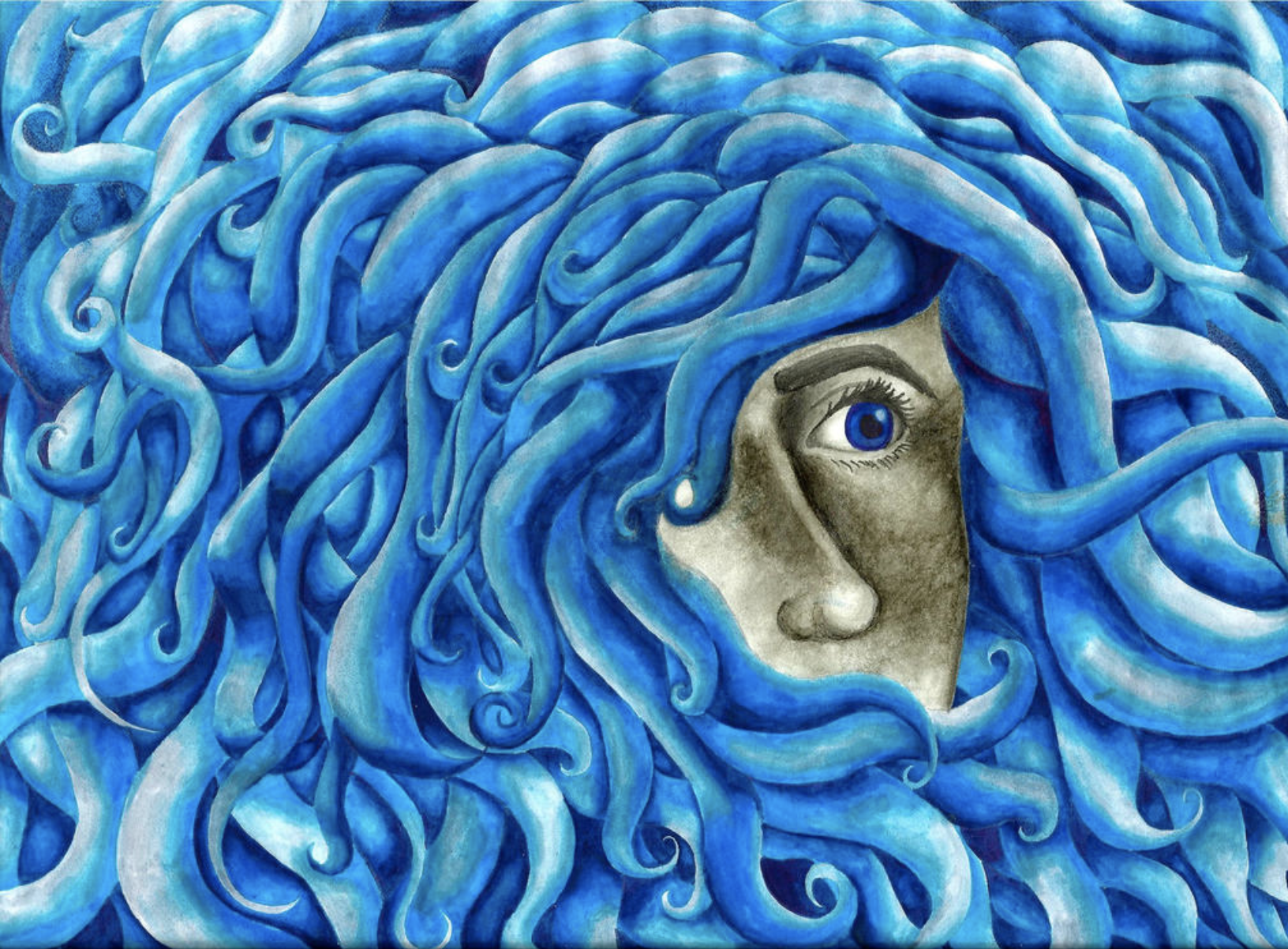

The other undercurrent to my art, visual as well as musical,

is the belief that using cheap tools can be a creative constraint rather

than a burden. After the Transitions concert, someone came up to me and asked

how I had made my piece. They guessed it was a sample pack in Ableton, but I

explained it was violin and guitar recorded into Audacity, with some processing

in SPEAR. Their reaction was

"you need to upgrade to ProTools!" - but why?

There is a lot ProTools can do that free programs like Audacity and SPEAR

cannot, but those features are not always needed for a piece to achieve its

goals. Clearly, my piece had made a positive impression without them. The

instinct to constantly upgrade tools lacks a certain level of critical

thinking about one's medium and the benefit of artificial constraints. In

visual art too, I have always loved using cheaper and readily available

supplies like markers and crayons. There are many things these tools cannot

do, but why not find the range of what they can?

The key to successful creative expression lies in matching

your aesthetic goals to your tools. As Ge lays out, there are an increasing

number of computer music languages, each with their own specialty. The

question is not how fancy your tools are, but how well-suited they are to

your design. Programming languages and DAWs alike obscure and give access to

features selectively, giving users different axes of control. When you are

running into walls trying to do something in open-source software, that's

when the upgrade to ProTools should happen - or when you can choose to work

with your medium instead of against it, and let it shape your aesthetic and

functional goals.

You just need something to make with to make art