shell object to invoke command-line programs from

within Max/MSP.CCRMA Documentation links: index contents overview rooms account staff about

(contents of this file: links to each section)

The “command line” (aka shell, terminal…) is an ancient way of interacting with computers by typing commands and seeing what they print. All the components of this programming style have been mature and widely available for Unix-like operating systems (including the Mac Terminal) for decades and are likely to persist long into the future of computing.

“Piping” these commands together connects them in potentially powerful ways; this creates an “ecosystem” of simple programs like echo, wc, tr, and grep that excel at one task and make sense in context. The programs that process the text are themselves text and can be the output of other programs. Writing raw html is painful and everbody should be able to use markdown instead.

This is great info: CS 107 Unix Guide

Here are some bash tutorials for beginners

A command-line shell (aka “Terminal”) is the part of the operating system that allows user interaction via typing commands and seeing what they print. It’s a form of Command-line interface; one way to “talk” to “a computer.” There are many Unix shells, often with names ending with “sh” (with bash one of the most common); they have important differences but are fundamentally similar. A shell is an interpreter for a programming language that excels at many kinds of tasks.

Everything occurs as a series of text within a specific window or teleprinter. First

the shell prints a prompt,

often just a single character such as $, telling you it’s

ready for input. Then you type your command (followed by the return key), then the

command runs,

possibly printing output text (to the same window, screen, or teleprinter ,

writing to files, making sound, etc. When the command finishes the shell

prints the next prompt and it starts all over; in normal usage you go

back and forth dozens or hundreds of times, issuing commands and seeing

what they print.

Each commmand begins with the name of a program, which is a series of letters and numbers. This might be one of the many standard programs found on most Unix-like operating systems or the name of an executable file in your search path, perhaps one of your own shell scripts.

For example, the program named date will print the

current time:

$ date

Tue Apr 6 15:49:09 PDT 2021After the program’s name there could be space followed by arguments

to the program. For example, the program echo

simply prints out the arguments it receives:

$ echo pleased to meet you

pleased to meet youAn option (aka flag or

switch) is a special kind of argument that controls the

behavior of the program in a case-by-case way. (Each program has its own

options.) For example, the program du

(“disk usage”) can take the option -s to print only a

summary of the disk usage:

$ du -s

126016 .It can also take the option -h to print the result in

“human-readable” form:

$ du -s -h

62M .Equivalently, these two options can be written together:

$ du -sh

62M .More simple commands include:

Filesystem: pwd,

ls, cd, pushd/popd

Login: logname, who,

exit

Text: echo/printf, grep, diff, sort, uniq, basename/dirname, awk, sed,

Search: grep, find

Time: sleep

/Applications/Utilities/Terminal.app

Many shell commands come pre-installed with your operating system. To add more, you probably want to use a package manager.

apt-get or equivalentMatt Wright’s brew install list January 2022: emacs,

svn, blackhole, sox, imagemagick, ffmpeg, ecasound, pandoc, pup,

midicsv, octave, musescore, libreoffice, macdown, sublime-text, mactex,

wget, mermaid-cli, youtube-dl, graphviz, openscad, cowsay

The shell itself has many nice and powerful features keeping track of what you already typed or might type so you don’t have to.

The best thing ever. You don’t have to type full names (of commands,

pfiles…); just the prefix then the tab key and it will

auto-complete.

See Autocomplete: CS107 Unix Guide

E.g., the up arrow will go back through the previous commands you typed, displaying each as if you had typed it, so you can either hit enter to do that thing again, or edit (like with left and right arrows, backspace, typing new text, or even EMACS cursor-movement key bindings) and then hit enter.

You put any commands you want into a text file and then you can call them just by typing the name of the file!

The script can optionally start with a line saying which shell or programming language is supposed to interpret the script, a “shebang”, like so:

#!/bin/bashYou probably have to make your script executable to be able to run

it, like with chmod

The script either needs to be in a directory in your search path, or

you go to (“cd”) the directory containing the file and refer to it

starting with ./ so for a script named foo you

would type

./fooAll the files on the computer have a directory structure that you can access from the command line.

Directory structure absolute / relative paths Being “in” a directory

See The Filesystem: CS107 Unix Guide and Commands To Navigate The Filesystem

The tree command (works at CCRMA, not Macintosh) is

great for seeing this.

One of the most powerful parts of Unix-like operating systems is the ability to redirect programs (text) input and/or output to and from files and other programs.

There are three special characters:

<>|=> in chuck)

Extract the fourth field from a TSV tab-separated values file:

cut -f4 myTSVfile.tsvExtract the fourth field from a CSV comma-separated values file:

cut -d, -f4 myCSVfile.csvExtract the fourth field from a CSV file, keeping only those that

“look like an email address”, i.e., letters and numbers followed by

@ followed by letters and numbers containing at least one

.:

cut -d, -f4 myCSVfile.csv | grep -E "[[:alnum:]]+@[[:alnum:]]+\.[[:alnum:]]+"Same thing, but extracting only the portion(s) of that field that look(s) like an email address:

cut -d, -f4 myCSVfile.csv | \

sed 's|.*\([:alnum:]\+@ XXX unfinished

Suppose you have a folder full of files that should each contain a certain string. You want to extract the text after that string and until another string, then make a single file containing just that one extracted bit from all the files, sorted.

s="url=https://ccrma.stanford.edu/~"

fgrep "$s" *.html | awk -F "$s" '{print $2}' | awk -F / '{print $1} | sortHere s is a bash variable that holds the certain string,

and the second string is just a single forward-slash character

/.

Print the lines of a file that contain a substring or match a pattern: grep

A whole programming language (awkwardly named based on the authors’ initials) based on iterating through each line (“record”) of a text file, breaking it into fields according to any delimiter (“field separator”), and executing code line-by-line or conditionally for certain lines.

Double-space a file:

awk '{ printf("%s\n\n", $0); } ' singlespaced.txt > doublespaced.txtSorry, this is the part that makes bash scripting really ugly.

Some characters have special meanings, for example * has

to do with sets of

filenames. Normally the shell treats * specially

(replacing the argument containing * with all the filenames

that match the pattern). So if you really mean the character

* you have to quote it somehow, e.g., with a backslash or 'single

quotes'.

$ echo *

[prints the name of every file in the current directory]

$ echo \*

*

$ echo '*'

*To have a command continue onto the next line you can put a backslash at the very end (thereby quoting the newline character ending the line, so that it doesn’t have its normal meaning of “this is the end of the command; please run it now” but rather it’s just another space character dividing the “words” of the command):

$ echo "hello" | \

> tr 0 a

hello(Note that the shell prints not just the usual

ready-for-the-next-command prompt $ but also the

ready-for-the-next-line-of-a-multiple-line-command prompt

>.)

for / while / continue / break

You can write the loop “interactively” from the shell prompt; with

each subsequent > prompt wanting more of the

for loop until it’s done:

$ for s in *

> do

> echo == $s

> fgrep "url=https://ccrma.stanford.edu" $s

> doneThen in terms of the shell’s history functions, it’s as if you’d typed it all on the same line; for example, the up-arrow button would give this:

$ for s in *; do echo == $s; fgrep "url=https://ccrma.stanford.edu" $s; doneThe point of this particular example is to show which files in the

directory do not contain a particular string

(url=https://ccrma.stanford.edu), by printing the name of

each (starting with something easy to parse visually, here

==) and then grepping for the string.

If two consecutive output lines both begin with ==, then

the first gives the name of a file that doesn’t contain the string.

The find command will look recursively (within

sub-subfolders) for files matching various criteria.

Show all .wav files anywhere within the current

directory:

find . -name \*.wav(The quoting of \* is so that the

shell will pass an actual * character to the find command

instead of doing its usual shell

expansion.)

Remove all .DS_Store files within the current directory:

find . -name .DS_Store -deleteThe name stands for secure (because your data are

encrypted, because they’re going over the Internet) version of

cp, where you’re supposed to know that cp

is the simple command that copies a

file. The basic syntax is that the first argument is the source (“from”)

and the second is the desination (“to”), both given as a filename or path.

If source and destination are both on the local machine then

scp is identical to cp; these two commands do

the same thing:

cp some-file.txt ../blah/blah/other-place-I-want-it

scp some-file.txt ../blah/blah/other-place-I-want-itWith scp the path can begin with an Internet

hostname. This example copies a file from the local machine (the one

I would type this command into) to a directory named

my-recordings within my CCRMA

home directory like this:

scp sound-I-just-recorded.wav matt@ccrma-gate.stanford.edu:my-recordingsLike cp, scp can also take the

-r flag to copy a directory “recursively” (meaning all its

contents, including any subdirectories and all of their contents,

including any subdirectories, etc., etc., recursively forever.)

A more complicated version of scp better for large

transfers or tricky situations. The good part is that if it gets

interrupted you can issue the same command, and (unlike

scp) it will be smart about noticing files that are already

identical between source and destination. So after running an

rsync that takes 10 hours, you could re-run the same

command and it might take only 10 seconds to discover that “there’s

nothing to do” because all the files are already there.

Here’s a good basic usage pattern:

rsync -avzh source destinationBreaking down -avzh:

Unix-like operating systems simultaneously run multiple processes.

You can list them with ps.

You can stop a naughty process with kill or

sometimes you need kill -9

Convert a sound file from wav to aiff:

$ sox soundfile.wav soundfile.aiffConvert a 10-channel sound file to 9 channels (by discarding the 10th):

$ sox input.wav output.wav remix 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9Convert four mono sound files into a single 4-channel soundfile:

$ sox -M -c 1 ARTIKULATION01_1.wav -c 1 ARTIKULATION02_2.wav -c 1 ARTIKULATION03_3.wav -c 1 ARTIKULATION04_4.wav Artiquad.wav“create, edit, compose, or convert digital images” (https://imagemagick.org)

Do anything with video files, e.g., stitch together 1000 still images into a movie file while adding a soundtrack from another file.

ecasound (https://ecasound.seul.org/ecasound) is an open-source command-line DAW; it can play or record multichannel sound files and much, much more.

Also MrsWatson a command-line audio plugin host.

Max’s third party (but maintained by a Cycling 74 employee) “shell” external lets you execute command-line commands from Max:

https://cycling74.com/forums/shell

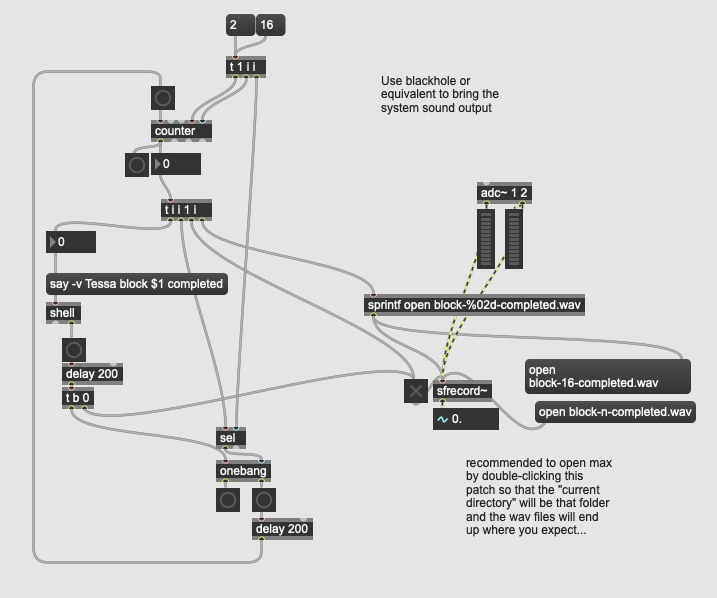

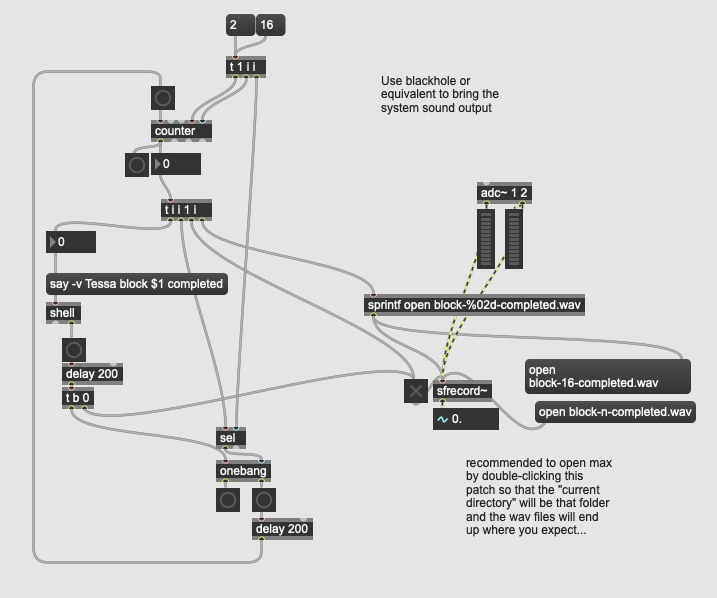

For example, here’s a Max patch that automates the recording of

utterances by the Mac say command, assuming that

system output sound is patched into MSP’s inputs (e.g., via

blackhole):

Same as above but in Max’s “copy compressed” format; you can copy this next block of gibberish and then paste into Max (5 or later):

----------begin_max5_patcher----------

1508.3ocyZssbiZCF9Z6mBMLsyzcFGO5.GL8t9NzdU2cxfMxNrACtfvIt6r4

Yu+RBhcRD1JFQRyNqYPH7m99O+K4eLch2xxG40dneG82nIS9wzISTCIGXR68

S71l73p7jZ0z7JZ1tjW4MS+nrT0fkK+9MTb2f6RpR1xE7pa4EIKy4xofaeF7

5YE4bg5KibbvxFQ2nz1Q0CINriqWeddyPdKSJ13g91yHIVcWVwlaq3qD5YQB

HywyfKL4k.r7SJcNF8M4q7yoSkeLyVxxe.nVGuD7GUf3kxySNfnXrAw.IzyD

UoFoJoOpdQZRCnJ9QVHuDRFCZJPKQFonumCzlJJBZzrBwYYZnhnrEQyITVXP

PLgEGsvONDFjNHZupb6VNf9q4Mfs5Io7TjnDUtiWffWDs7.JsrALnuYUd1p6

gkIRbWVMRsnQ0kvcIB3CN5qdqZppfuaTZljIkUG9pG5gr7bzRtdZqKyS4Unj

hT0a7Pxdz5rbdsdV.3nlcnGtiWwQGJaP7G2AeOymOua0lmU.KylB0RN7sJoE

uCcDteouuV76qcmHAAxKft35j3a400Ia3uQhqDwKyKWc+ME2.B+cvJimNGDJ

FL+XAtvC6r1bAL+4A.qw5XIii604hhv7+Phhz5aEBJWBNJfFtXAIhhYrAGRY

YiPTVXhYLGklXvwN8AyXPIS8UD024Dk94STRn6HZOVwkEbcj72J.vuCa3Kll

vZxFpR4qCTc8trppbdpi.aKS4mtJOMYX7YY45xBQc1+pdahzr6bjuNaix134

oIe6Bv1Qg1eTkkj60mbBd2B4iQdqyKSNeJUeHwoJ7lxtHL7nn5DbWmrRaodE

hOQ4lM4bSkNrXrcJtT4D9XljzrnENvmvh7YjPyIzdQ9aS1UrwOKGUkkiEDqy

xorCXAtM9P8tJPkrFchH4WwzzKlkOzyAFCmk9xzdRSfXsM.cTRxWuVVMYU5S

lbFbAEa86svcmEEKun01tOwNM9SOeWaueKB6bpGfqceMG7W0bvLNY082UlyQ

kUH9+zjsOIWVrOzrvxJcaAbT8gZAeKzVPCTKOvkcMBi99LChxH2T7NKJRJCh

Z6HVkXz+5qcWbRFwSWsAtvN9xYsBv5b5Xc3JciuXmyF+OF13q0MtgM8D7IIc

0SHBhZhlLWzC+whNrILjlwjETGTfVuggHQe9ggnAmrETiSY2BTF7OBJyjH38

3P5etBolY5xYoNz1HC9KhE29GEDDwws6EWvHjfkmaRDPbYuGV02AU6OGOFjT

H0zl0032gtlYut9rLlpXbfl2CaGV6qBZSwrhG8JhaYFw2Apx9X1wMH9DpEM9

TCB3F3Hp0iUppjFimMf4.RAWU.ot+ewPQsGD.E6fcHu2zMQAe5oaZ2DO1HtI

O02wyMEl02IUQX0163q6NES6ZR8UaYQcxdd5svhBdiaSDhpLPmoOZqIOS1Is

LQt9+sT95jlbwW7TORInttsIxjf4+EmElVlQYDGbTX8ENqN4.5l8n+T9Xc+8

negfdt6dSkdN5w5Z4cD6j5MeCwUeApVwd04ep9Bki+RoAzHW0pN3aSGgNZ+k

xqEYEIhLHLww4HSOi5SfaKPxXLWDI4IFLbj9nnTnM.AAWf5d5lTYUJ3p06FR

5TjewbdFXxf.1FkHEaFY7niLIZL3r+KUglgty7dXHYiz0A3vBr29YX.YCiHt

voWdhbWFoPWfD1BygtkyvQ5hgLcgAA0lz.tvBmZiuDMXLBfPswBg5+oA8nDu

1J483frMFuDmXSYAP9tveTdteeHgMI1je+U9rayR2UBsS1VGHE5UTdNIc8Uo

2qiStoc+zCU6mk7lgtlkpR1EVytH9KwljW9tBH5kT2KbERWzK0IVV1jPlgcE

RjODoGwVNQFJRXKSSxbAPDK.x2E.QswxavxNahcF+FyAcCtI61smWU2NaEFP

i8euTkmZwL0sYE5aU8f6Uw2m0MeU+2dIUPG1Bn85lJ8OEkGC0avg5GFSUQSV

aROfc.jpMMP9yVodW6ugD0dKL8mS+OP8GHAH

-----------end_max5_patcher-----------graphviz makes the feedback topology visualizations in real time for https://github.com/create-ensemble/feedback

Yes there are many computer games whose graphics and interaction are all based on command line; here are serveral: https://linoxide.com/linux-command-line-games

The command-line way to emulate double-clicking on any file. For directories it will open a Finder window. For html files it will open the page in your default browser. Etc.

macintosh$ open .

macintosh$ open foo.html

macintosh$ open foo.maxpat

macintosh$ open https://ccrma.stanford.edu/docs/common/command-line.htmlYou can even open a specific Mail folder as a window in the Apple

Mail client if you can find the corresponding .mbox file

somewhere within your ~/Library/Mail/

The inverse of this is that if you drag a folder or file from the

Finder onto a Mac Terminal, the full path to that file

will appear as if you’d just pasted it. So you might type

cd plus a space, then drag a folder onto the Terminal

window.

Interaction with the macOS copy/paste clipboard (aka “paste” board,

hence pb).

Example: How many words are in the copied text?

pbpaste | wc -wExample: suppose you have selected and copied a range of cells in a

spreadsheet in a web browser, and you want to know how many unique

values it contains. (Converts tabs to newlines with

tr '\t' '\n' so each cell becomes its own line.)

pbpaste | tr '\t' '\n' | sort | uniqExample: same thing except the cells contain comma-separated lists of values and you want to know the number of times each value appears, counting values the same in spite of capitalization or any extra numeric digits (so that “Hi” = “hi” = “h1I222”). :

pbpaste | tr '[:upper:]' '[:lower:]' | tr -d '[:digit:]' | tr , '\n' | tr -d ' ' | sort | uniq -c | sort -nrExample: use the command-line (sed) to search+replace within the currently-copied text:

pbpaste | sed -e ‘s/foo/bar/g’ | pbcopyExample: use octave with no GUI (the flag

--no-gui-libs makes it instead a good old fashioned

command-line program) to make up a string of 20 random characters (i.e.,

to be a password), save them in the copy buffer, and also print

them:

#!/bin/bash

echo 'length=20; disp(char(int8(48+rand(1,length)*(122-48))))' \

| octave --no-gui-libs | pbcopy

pbpastemacintosh$ say help I am trapped inside this computer

macintosh$ say -v Victoria hello my name is victoria

macintosh$ say -v \?Matt’s saynames.sh script:

voices=`say -v \? | awk '{print $1}'`;

for v in $voices; do

echo "My name is $v"

say -v $v "My name is $v"

doneYou can invoke AppleScript commands with osascript.

Example: Open Sound Preferences and go to the “input” tab:

osascript -e 'tell application "System Preferences" to activate'

osascript -e 'tell application "System Preferences" to reveal anchor "input" of pane id "com.apple.preference.sound"'Example: Set the system sound volume (like what a laptop’s “louder”/“quieter” buttons change) to a value from 0 to 10 (in this case 8):

osascript -e "set Volume 8"You can launch jackd and jacktrip then make and break JACK connections, all from command-line.

Convert a text file into one that the Max/MSP coll object can read (line number, then a comma, then the data, then a semicolon):

awk '{printf("%d, %s;\n", NR, $0)}' data.txt > data.coll.txtConvert a CSV file into the same kind of “coll” file (script that takes the CSV filename as argument), where the first column of the CSV is the part before the comma and all the other columns are the data:

#!/bin/bash

outfile=`basename $1 .csv`.coll.txt

echo converting CSV $1 to a Max \"coll\" text file $outfile

awk -F, '{printf("%s, ", $1); for(i=2;i<=NF;i++) printf $i" "; print ";"}' \

$1 > $outfileEvery SLOrk piece has one or more corresponding bash scripts that launch and initiate any software that needs to run on a particular laptop in order to play the piece.

The most commonly run “piece” is hemi-test, just a

series of clicks out the six channels of the hemispherical

loudspeaker attached to this machine:

system-sound-to-motu

pushd ~/slork/users/ge/hemi-test/

chuck --bufsize256 -c8 impulse.ck

popdThis first sets the system sound to use a particular audio interface,

by calling another script system-sound-to-motu (which uses

another program audiodevice that is not built in). Then it

uses pushd to go to the directory containing the files for

the piece, invokes chuck from the command line to run a

certain chuck program with certain settings, then uses popd

to go back to the original directory.

At least one script uses pipe, the one for Perry Cook’s piece “Take it for Granite” (YouTube). A user

interface written in tcl/tk outputs

text, which the Chuck program parses in realtime to control the

sound generation. The script granite starts the software

(using the same pushd/popd technique as

hemi-test):

pushd ~/slork/users/prc/granite/

wish granite.tcl | chuck -c8 granite.ck

popdThe script could take an argument such as a number from 1 to 12 for

“which player am I?”, for example allegory (which in turn

passes the client number to an even

more complicated script feedjack-client):

#!/bin/bash

if test $# -ne 1; then

echo usage: $0 [client-number]

exit -1

fi

pushd ~/slork/users/matt/allegory-2018/

open Allegory-program-notes.rtf

open Allegory-detailed-performer-instructions.rtf

open ~/slork/users/matt/max-choose-JackRouter.maxpat

open allegory.maxpat

popd

feedjack-client $1 ~/slork/users/matt/allegory-2018/allegory.maxpatAnd in case you can’t remember the names of the scripts needed for

this concert’s pieces, there’s a script that prints (a text file

containing) the names of the other scripts, e.g.,

print2019scripts:

FILE=/Users/slork/slork/docs/perform/2019.06.08/bing2019.txt

cat $FILE

echo $FILEAnd in case you can’t remember what year it is or type more than one

letter, there’s another script named simply p, updated

annually, that calls the print script for this year. The file

p literally contains nothing more than the name of the

other script:

print2019scriptsLast but not least, the most popular script die, which

forcibly kills every program that might be lingering after running a

SLOrk piece:

killall chuck; killall miniAudicle; killall audicle

kill -9 `ps -ef | grep /Applications/Max.app | awk '{print $2}'`

kill -9 `ps -ef | grep /Applications/FaceTime.app | awk '{print $2}'`

kill -9 `ps -ef | grep /Applications/Wekinator.app | awk '{print $2}'`

kill -9 `ps -ef | grep FaceOSC_Wekinator_14Inputs.app | awk '{print $2}'`

kill -9 `ps -ef | grep /users/lja/vr2019 | awk '{print $2}'`

killall jacktrip; killall jackd

killall FaceOSC; killall python

killall PreviewYou don’t want to know.

The command-line way to download one file from a web server. For example, you could download and print the source for this very web page:

curl https://ccrma.stanford.edu/docs/common/command-line.mdThe command-line way to download a web page, entire website, etc. The

-r flag makes it recursive (grabbing not just the

page but also the pages that the page links to, and the pages those link

to, etc., up to the “level” of recursion set with - l).

Example: download a copy of Graham Coleman’s Chuck tutorial from the Internet Archive WayBack machine, specifically, from this 2015 snapshot, including the files that it links to, but only the ones from his website, not the ones that are links to chuck documentation, etc.

wget -r -l 3 --accept-regex '.*/web.archive.org/.*/~gcoleman/.*' \

http://web.archive.org/web/20150320041518/http://www.dtic.upf.edu/~gcoleman/chuck/tutorial/tutorial.htmlpandoc, “a universal document converter” (pandoc.org) is one of the best things

ever.

Among many many other formats, it can convert from [markdown format](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Markdown] to HTML, so you never have to code raw HTML again:

pandoc foo.md -o foo.htmlConvert every .md file in this directory to the

corresponding .html file:

for m in *.md;

do

echo converting $m;

pandoc $m -o `basename $m md`html;

doneOne-line version:

for m in *.md; do pandoc $m -o `basename $m md`html; doneGo through every Markdown file (whose name ends with

.md) within the current directory (recursively looking in

sub-sub-directories etc.) looking for a certain URL (https://en.wikipedia.org):

$ grep -nri https://en.wikipedia.org . --include \*.md

[...prints many lines of many files...]Whoa that’s a lot! Same thing pipe

wc:

$ grep -nri https://en.wikipedia.org . --include \*.md | wc

182 528 17428OK, but how many unique links are there? We don’t want to figure out how to search for all the ways you can put links in Markdown; we’d be better off parsing html with pup.

Pup “is a command line tool for processing HTML.”

Extract all the links from an html file:

pup 'a attr{href}' < foo.html Extract all the headings from an html file:

pup 'h1,h2,h3,h4,h5,h6' < foo.htmlShow all the links in all the Markdown files in this directory and

all its subdirectories (printing a blank line and the name of each

md file before printing all its links):

for m in *.md */*.md

do

echo " "

echo $m

pandoc $m -t html | pup 'a attr{href}'

doneList all the URLs linked to from all of the Markdown files in this directory and all its subdirectories:

cat */*.md *.md | pandoc -t html | pup 'a attr{href}'Same thing but only the unique links (in alphabetical order):

pandoc */*.md *.md -t html | pup 'a attr{href}' | sort | uniqThis page is part of an overall “CCRMA Docs” documentation effort with a somewhat detailed “About” / README page including links to the scripts that build the site including a simple navigation system and an automatically-generated list of pages and overall table of contents. Each page links to its own section of the overall table of contents.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/In_the_Beginning..._Was_the_Command_Line

This page of CCRMA documentation last committed on Tue Oct 29 14:01:17 2024 -0700 by Matthew James Wright. Stanford has a page for Digital Accessibility.