Matt Wright, November 2005

I have compared two recordings of “Akbai,” a piece of music from Kazakhstan for the dombra, a fretted, two-stringed, plucked instrument. One recording was by Qarshymbai Akhmediarov, an older gentleman representing a more traditional musical style, and the second was by Aygul, a young woman with much more fame and popularity.

| Akhmediarov | Aygul | |

| Total duration | 3:44 | 2:44 |

| Average tempo | ||

| Total number of notes |

Akhmediarov's performance lasts 3 minutes and 44 seconds; Aygul's performance lasts 2 minutes and 44 seconds. This is partly because Aygul takes a faster overall tempo. But more importantly, Aygul's version of the piece has less repetition, resulting in fewer overall notes. For example, Akhmediarov establishes the opening note with 16 repetitions before introducing the second pitch of the melody, whereas Aygul plays the opening note only 8 times before moving on.

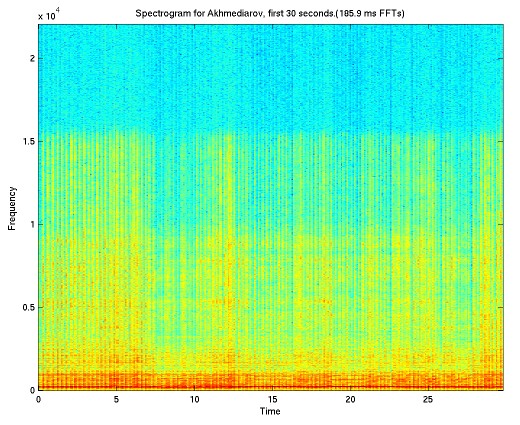

Here are spectrograms of the two performances. The horizontal axis is time, the vertical axis is frequency, and the color shading indicates the amount of energy, from cooler blue colors showing little energy to warmer red colors showing more energy.

(Here are larger images (2M each) of the same spectograms for Akhmediarov and Aygul.)

For more detail, here are the same images, but showing only the first 30 seconds of each recording:

Comparing these, we see that both have the same basic structure of more energy in low frequencies (which is typical for all music) with clearly-visible notes appearing as vertical stripes of greater energy. Aygul's performance has more high frequencies overall, probably due to recording and production techniques (which I believe were influenced by the brighter sounds of western pop music). Also, one can see in Akhmediarov's performance that there is more variety in the heights of the vertical stripes for each note, meaning more variety in the brightness of the notes that he plays.

This diagram compares the overall amount of energy at each frequency throughout the two performances. (In other words, it is not a function of time, but the total for each performance.)

Again, for both curves we see the general overall pattern of more energy at low frequencies compared to high frequencies. Aygul has more high-frequency energy overall, especially at the upper reaches of human hearing. But note that in the region from 6 Kilohertz to 9 Kilohertz Akhmediarov has more energy. For dombra playing, these frequencies are generated only by the noise at the beginning of each note, so this may indicate that Akhmediarov has a noisier, more percussive style of attacking the notes. On the other hand, it may again just be a function of the recording technology and technique.

What strikes me the most about this style of playing is the timing. Although the piece is very rhythmic and driving, the tempo varies substantially, an effect that would be called "rubato" in Western music.

To analyze this, I painstakingly marked the instant of each note attack. I used a combination of listening to the orignal recordings and listening to only the high-frequency parts of each recording, which as mentioned above contain only attack noise, not the tone of the notes:

Here are my results. The right channel comes from the original recording; the left channel is a click at every instant where I found a note had just begun.

One amazing result of this process is how much of the feeling of each performance is preserved when listening only to the timing of these clicks! Try listening to just the click part of one of these sound files, and you'll see that even without any pitch, loudness, timbre, or duration from the original recordings, there is still a sense of human-ness in these click tracks, conveyed entirely by the timing.

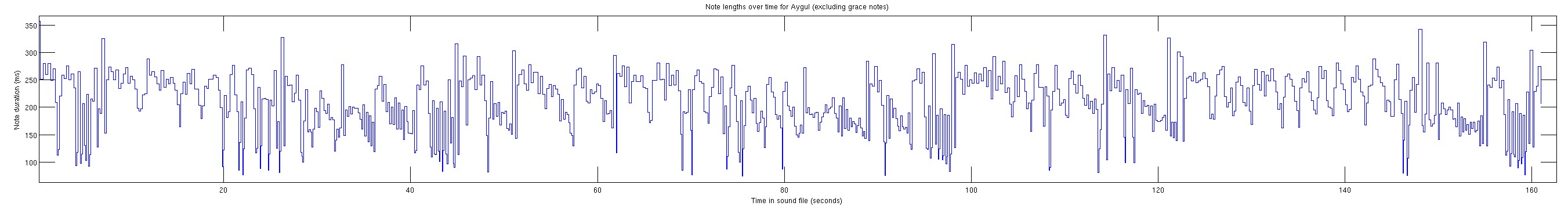

Here are graphs of the note durations in each performance. The horizontal axis is the time that each note started, and the vertical axis is the duration of the note. (So the graph is redundant, because each bar's height (duration) is proportional to its width (the time to the next note).) I have made these graphs extremely wide (three screenfuls) so that you can see the entire piece with sufficient resolution.

These graphs clearly show that the timings of notes in both performances are regular but not too regular. In particualr, there are some series of consecutive notes of approximately the same duration (indicating a steady local tempo), but that in general there's lots of flux and irregularity in the note timings.

One stark difference between the two performances is that Akhmediarov's longest note (near the end of his performance) is 800 milliseconds, more than twice as long as Aygul's longest note, showing that he makes more of the pause near the end of the piece. I believe that the ability to sustain a meaningful pause is a sign of musical maturity.

I used an ad-hoc method to label certain of the notes as "beats", to account for the fact that some of the notes seem to come two to the beat, whereas others come one to the beat.

Once I had the time of each beat I could take the reciprocal of each beat's duration to get the "instantaneous tempo". This plot compares the instantaneous tempo curves of the two performances. (The time axis is stretched so that both will be the same width in spite of Aygul's performance being much shorter in duration. The blue curve is Akhmediarov and the green curve is Aygul.