RR5 | Music 256A

Cody Hergenroeder

10/24/21

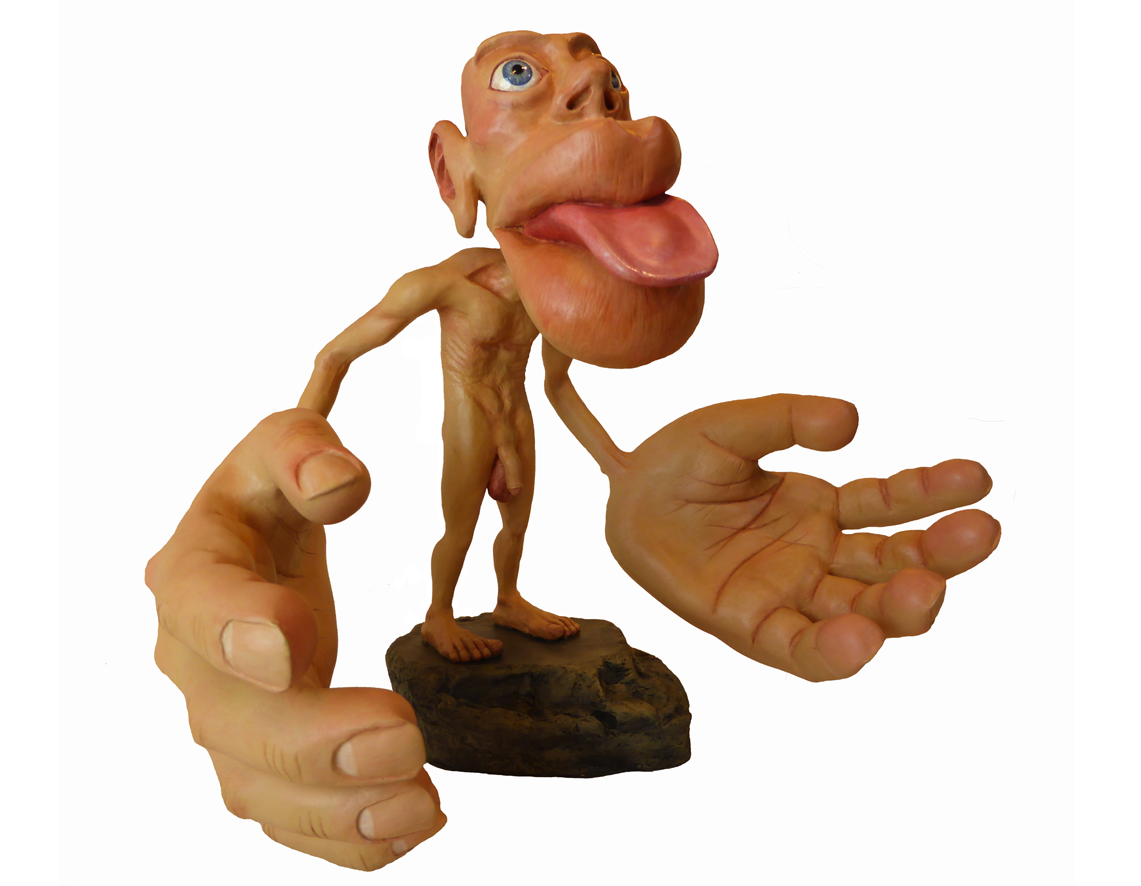

Ge Wang's 'Artful Design': Chapter 5

This week I'm reflecting on Principle 5.4: Bodies Matter (210). I found the homonculoid illustrations extending from 212-214 to be particularly mind-bending (reminding me of this guy), doing a great job at illustrating how a human-computer interface "co-creates" the human it interacts with. In the same way that the human mind creates the sensory "homunculus" shown above, a pianist from the perspective of the piano is, for all intents and purposes, just an eye (if necessary), some fingers, a pair of well-tuned ears, and a pedal-stomping foot. It's great to think about human-computer interaction from the bottom up this way, imagining how the interactions that are possible are defining us in each moment, as we experience ourselves through the interaction. This style of thinking elucidates how social interaction between humans is the gold-standard for human-interaction systems, making fullest use of our bodies' innate expressiveness (the body<->body evolutionary design loop sure helped!): we react to each others' subtle facial expressions, eye movements, and body postures, experiencing their experience of us; on our side, our own body shifts to match our emotional experience, to be read by another. Our bodies do a fantastic job at defining each other because they goad our fullest expressiveness and shirk limitations, causing us to laugh, dance, play, fight, run, and throw up--hopefully not all at once. Our bodies are steeped with meaning and expressive capabilities, and when we are interacting with a computer, we engage in an aesthetic interchange that re-contextualizes everyday bodily actions in a way that can alter or extend their meanings and expressiveness. How do HCI systems compare? (more text down below... vvv)

Firstly, this re-contextualization adds much more gravity & sacredness to the design process. Because the human is co-created by the interface it interacts with, we are entrusting the nature of our humanity to the designers of the systems we use. But who among us can be said to understand the human condition enough to be entrusted with the sacred responsibility of creating a container for it? I know Facebook doesn't have my best interests at heart--I can feel myself becoming a scrolling, clicking, dopamine-driven brain-in-a-jar when I use their website. I must masochistically click on notifications I know are irrelevant because it glows bright red with a number, I must endlessly doomscroll because there's nowhere else to go. A contraction of my humanity molded by greed, probably. Let this be a kind of manifesto that all designers be humanistic/transhumanistic philosophers, exploring the human condition and the necessity of designing our technological systems to EXPAND human expressiveness, CULTIVATE human joy, and IMPROVE upon what it means to be a human. The alternative is unsavory, may the expression of our bodily dissatisfaction guide us to its positive opposite.

This naturally segues into Principle 5.5: Interfaces Extend Us (218). Taken together with the previous principle, we might re-write this: "Interfaces Extend Us (and our bodies!)". Indeed, HCI interfaces do extend the functionality of our minds but should ideally take advantage of their service as a mirror of ourselves, and help us embody our wandering minds. We live in a world where we think aloud to ourselves and other with finger gestures, body language, and eye contact. Where we crave intimacy for all the right buttons it presses inside us, and yet are stuck refreshing Facebook. Technology should extend the use cases for our natural methods of self-expression, by transcending traditional limitations and allowing us to explore transhumanistically questions like: what is a human body for? What does a human body do? May we discover something all-at-once beautiful and terrifying at the end of the rainbow.

Good luck, us!