Next |

Prev |

Up |

Top

|

Index |

JOS Index |

JOS Pubs |

JOS Home |

Search

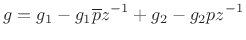

Note that every real two-pole resonator can be broken up into a sum of

two complex one-pole resonators:

|

(B.7) |

where  and

and  are constants (generally complex). In this

``parallel one-pole'' form, it can be seen that the peak gain is no

longer equal to the resonance gain, since each one-pole frequency

response is ``tilted'' near resonance by being summed with the

``skirt'' of the other one-pole resonator, as illustrated in

Fig.B.9. This interaction between the positive- and negative-frequency

poles is minimized by making the resonance sharper (

are constants (generally complex). In this

``parallel one-pole'' form, it can be seen that the peak gain is no

longer equal to the resonance gain, since each one-pole frequency

response is ``tilted'' near resonance by being summed with the

``skirt'' of the other one-pole resonator, as illustrated in

Fig.B.9. This interaction between the positive- and negative-frequency

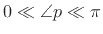

poles is minimized by making the resonance sharper (

),

and by separating the pole frequencies

),

and by separating the pole frequencies

. The

greatest separation occurs when the resonance frequency is at

one-fourth the sampling rate (

. The

greatest separation occurs when the resonance frequency is at

one-fourth the sampling rate (

). However,

low-frequency resonances, which are by far the most common in audio

work, suffer from significant overlapping of the positive- and

negative-frequency poles.

). However,

low-frequency resonances, which are by far the most common in audio

work, suffer from significant overlapping of the positive- and

negative-frequency poles.

To show Eq.(B.7) is always true, let's solve in general for  and

and  given

given  and

and  . Recombining the right-hand side

over a common denominator and equating numerators gives

. Recombining the right-hand side

over a common denominator and equating numerators gives

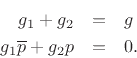

which implies

The solution is easily found to be

where we have assumed

im , as necessary to have a

resonator in the first place.

, as necessary to have a

resonator in the first place.

Breaking up the two-pole real resonator into a parallel sum of two

complex one-pole resonators is a simple example of a partial

fraction expansion (PFE) (discussed more fully in §6.8).

Note that the inverse z transform of a sum of one-pole transfer

functions can be easily written down by inspection. In particular,

the impulse response of the PFE of the two-pole resonator (see

Eq.(B.7)) is clearly

Since  is real, we must have

is real, we must have

, as we found above

without assuming it. If

, as we found above

without assuming it. If

, then

, then  is a real sinusoid

created by the sum of two complex sinusoids spinning in opposite

directions on the unit circle.

is a real sinusoid

created by the sum of two complex sinusoids spinning in opposite

directions on the unit circle.

Next |

Prev |

Up |

Top

|

Index |

JOS Index |

JOS Pubs |

JOS Home |

Search

[How to cite this work] [Order a printed hardcopy] [Comment on this page via email]

![\includegraphics[width=\twidth ]{eps/tppfe}](img1428.png)

![]() and

and ![]() given

given ![]() and

and ![]() . Recombining the right-hand side

over a common denominator and equating numerators gives

. Recombining the right-hand side

over a common denominator and equating numerators gives

![]() , as necessary to have a

resonator in the first place.

, as necessary to have a

resonator in the first place.