Inducing Unusual Dynamics in Acoustic Musical Instruments

Sound Examples and Additional Info

Edgar Berdahl

September, 2007

This is the website corresponding to the paper:

Brief note on resonant ring modulation:

Websites for related conference papers:

I. Examples With Multiple Equilibria

Figure 1. Ten plucks with linearly increasing magnitude (above), Corresponding

loop gain L(t) (below)

Fig. 1 shows the results from the simulation where the string is

virtually plucked ten times with initial conditions corresponding to increasing

magnitudes. Fig. 1 (top) demonstrates that the final

equilibrium RMS state depends on the initial condition. Four different stable

equilibria in xp are evident.

Fig. 1 (bottom) reveals that for each pluck, the loop gain L

first wraps around a number of times while the energy outside the main resonances decays,

and then L converges to the value inducing marginal stability as desired.

Because velocity feedback is used instead of the integral of displacement

feedback, the balance between the energy in the various harmonics does not change much even as the level is driven to a target.

| The RMS level is quickly driven to a neighboring target.

Some slight distortion may be heard directly following the attacks. This

corresponds to L(t) varying wildly as the level detector first starts

seeing the transient.

|

II. Band-Pass Filter Effect

The bandpass filter effect may also be used advantageously to control the RMS level

of a single

mode without affecting others. This involves tuning a high-Q band-pass

filter (two-pole, no zeros) to the mode in question.

| Here the

band-pass filter is tuned to the second harmonic. Positive

feedback is applied in order to damp the second harmonic quickly. The other

harmonics remain unchanged.

|

| This is the same as above, except that negative

feedback is applied to increase the decay time constant of the second harmonic.

|

The block diagram in Fig. 2 shows in particular how multiple channels may be

connected together to control multiple harmonics simultaneously.

Figure 2. System block diagram for implementing

multiple level-regulating

controllers concurrently

The 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, 6th, 9th, and 10th harmonics were controlled

simultaneously in order to make the vibrating string model sing. To this end,

they were driven to the spectral envelope outlined by the three formants f1,

f2, and f3 for the the short u and a vowels. Since the sensor

and actuator were placed realistically in the model accoring to real physical

characterstics, both the 7th and 8th harmonics are both harder to sense and

actuate. This is a controllability/observability problem due to the sensor and

actuator being placed near a node for the 7th and 8th harmonics. Thus, we did not attempt to control them due to signal to noise

ratio considerations (see discussion regarding Fig. 5). This means that the formants are not

perfectly modeled, but it still should be possible to hear which vowel is being

"sung." Fig. 3 shows the performance of the controller for the second

harmonic. The initial pluck at t=0s causes some overshoot of the target

and the loop gain L2 to be underestimated. However, soon the disturbance

subsides and the controller adapts to the correct loop gain using the

adaptive controller. Then at t=5s, the target vowel switches from

u to a. After a few seconds, the RMS level is again driven to

the correct target. Of course in both cases the same loop gain is used to

induce marginal stability as soon as the target RMS level is achieved.

Figure 3. Driving the RMS of the second harmonic to 135 until

t=5, at which

point the RMS is driven to 24

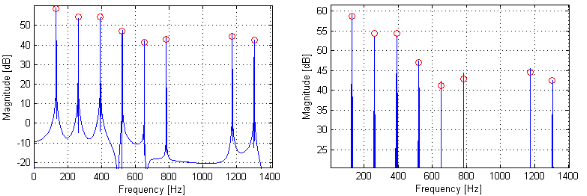

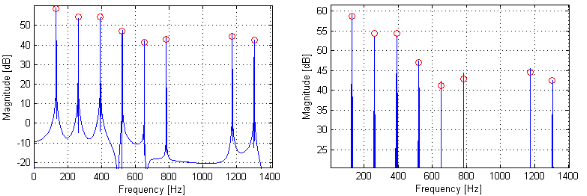

The match of the spectra was quite good. Fig. 4 shows the spectrum in blue of

x at the end of the u vowel after the system has nearly converged to the

steady-state solution. The red circles are the targets as specified by the

formants of the vowel.

Figure 4. Match between the desired levels and the attained levels (left,

zoomed out; right, zoomed in)

The match is quite good (within +/-1.5dB) given the controller is non-ideal in some ways. For

example, band-pass filters that are not perfectly tuned to the harmonic will

impart a gain error. This means that, even though the adaptive controller

for a given harmonic believes it has achieved the target, it may be slightly

off-target because the band-pass filter is mistuned. Another non-ideality is

that dividing signals by RMS level estimates leads to some harmonic

distortion. Fig. 5 shows the spectrum of the nearly steady-state signal

u1, which is the control signal for the first harmonic, as

estimated from the same time frame as Fig. 4.

Figure 5. Spectrum of steady-state signal

u1

| This is the

sound of the eight harmonics being controlled as explained above to synthesize a u and then

an a vowel.

|

| This is essentially the same example except

that some modulation has been added because this aids in perceiving vowels. In

particular, the error signals were slightly amplitude modulated at 1Hz.

|

III. Resonant Ring Modulation

Figure 6. RMS levels for resonant ring modulation

Resonant ring modulation involves amplitude modulating the feedback signal by a

sinusoid with carrier frequency fc. For more information,

see an Analysis Of Resonant Ring Modulation. One

difference here, which holds for all of the following examples except for the

last two, is that an additional first-order low-pass filter is applied in

the feedback loop preceeding the modulation to form the effect. This helps

improve the sound quality by preventing too much energy from being stored in

the higher harmonics.

Here fc is swept linearly from f0 to 2.05f0:

| In this case, the loop gain L is held constant. This

corresponds to the blue line in Fig. 6. Note how the quieter sections sound

somewhat hollow because the controller is not driving the plant hard enough

during these sections. This example has a noticeable pluck at the beginning

because the loop gain L begins at the constant.

|

| This time, the adaptive controller is applied to drive

the RMS level to a target. This not only reduces the dynamic range of the

instrument's output, but it also helps shift the applied parameters closer to

the space of interesting-sounding ones. For instance, this sound does not

contain any "hollow"-sounding sections. Note that this example does not have a

noticeable pluck at the beginning because the loop gain L begins at zero.

|

Here fc is swept linearly from f0 to 4.05f0:

| Now fc

is swept over a much larger range revealing more parts of the space with unique

dynamics. The adaptive controller is applied here.

|

| This is the same as above, except that we are listening

to a limited version of the feedback signal rather than the output from the

string itself. Note that as a result, it sounds less resonant because we do

not tend to hear the natural string harmonics ringing out because they are

instead modulated.

|

For the last two examples, the simplest form of resonant ring modulation is

implemented. That is, there is no low-pass filter in the feedback loop, and so

the sound examples may sound tinny due to the additional higher-frequency content:

| Here we

have another example of a three octave sweep using the adaptive controller.

|

| This is the example

from the note on resonant ring modulation. We can hear the

partials converge to the target spectrum.

|