Research in Underwater Sound

With Focus on Musical Applications and Computer Synthesis

+

+  =

=

©

March 15, 1998

+

+  =

=

Table of Contents:

Introduction

My beginning research in underwater acoustics last Spring (1997) exposed me to various sources on the topic that were not directly relevant to the musical directions I have wished to explore. Since the available literature is mostly concerned with applications of sonar, the books I had studied on underwater acoustics—Finn B. Jensen's Computational Ocean Acoustics (1993) and P. C. Etter's Underwater Acoustics Modeling (1996)—dealt primarily with propagation paths of sound sources in the ocean; and though the introductory physics of how sound travels in water is valuable to understand, such knowledge describes nothing about the actual sound itself: i.e. I knew how the sounds moved now, but how did they sound? Since my concern has been with the aural result of sound underwater, I still needed to find sources that could relate how water manipulates what is heard of sounds compared to that which is normally heard in air: what transformations do sounds undergo when water is the propagating medium as opposed to air? If I throw my jazz combo into the deep end of a pool, for example, (pending we have oxygen) what's going to happen to our music? Or what's going to happen to music that is broadcasted through loudspeakers underwater?

Last quarter, studies in architectural acoustics temporarily avoided my hazy understanding of underwater sound, and I was able to mimic, somewhat, the effect of water on sound without any physical understanding: conversations with my advisor Chris Chafe at CCRMA and readings into F. Richard Moore's Elements of Computer Music (1990) revealed a process by which the acoustics of any particular soundscape could be captured for synthesis on the computer with digital signal processing techniques. One such process of capturing the reverberation quality of a room—room meaning "pool" for our purposes, or any other body of water—entails the convolution of a recorded impulse response of that room with the given sound source. Since this synthesis technique, furthermore, merely involves masking the acoustic soundscape of the recorded impulse response onto a sound file, no scientific understanding of the acoustic soundscape or impulse response is required. The results of this process as applied to a pool environment were somewhat unconvincing, however, (let alone computationally inefficient) and I have hoped that a better understanding of underwater sound may allow me to comprehend what is lacking in this convolution process and also to employ better methods.

My research last Spring also introduced me to a unique composer who has already employed water as a medium for musical exploration for many years: French-born electronic music composer Michel Redolfi. A search for "underwater music" in Stanford's library system immediately incited me to set up a listening appointment at the Archive of Recorded Sound to hear Redolfi's 1983 recording, Sonic Waters, which includes hydrophone recordings of original electronic music which he had broadcasted in the ocean off the coast of La Jolla, California and in several university pools for the world's first underwater concerts!!! As I will expound upon later, I actually got in touch with Monsieur Redolfi this quarter, who continues to explore underwater music and currently co-directs the Centre International de Recherche Musicale (CIRM) in Nice, France.

Introduction • Main Body • Closing • Sound Samples • References • Equipment Catalog • Top

Main Body

Contents:

* * *Hydrophone vs. Microphone

My objectives this quarter have been primarily two-fold: (a.) to understand the aural results of playing sounds underwater, and (b.) to understand the fundamental difference in construction between a microphone and its underwater counterpart, the hydrophone. As regards the hydrophone, it was a failed attempt of mine last quarter, for the most part, trying to employ a microphone for underwater recording applications. Merely covering a normal microphone with waterproof material (a balloon, for example) proves altogether ridiculous, as amplifying the signal to even the highest extremes on the recording device will not reveal much of anything—even if you yell into it underwater at close range: obviously there is a reason they had to invent the hydrophone; what this reason is, I wanted to know. With regards to aural results, I have already explained this concern in my introduction. Searching the internet for hydrophones this quarter put me in contact with the International Transducer Corporation (ITC) of Santa Barbara, CA, which proved to be the springboard I needed for my research and sparked a chain of other important contacts.

My correspondence with ITC ultimately achieved my second objective in trying to understand the design features of hydrophones as opposed to microphones. The problem in using microphones underwater, ITC informed me, is that they are not constructed to match the impedance of water. Essentially, water is a much more resistant substance than air, and, thus, greater forces are required to drive pressure displacements in water, and materials must be selected that can sense and generate these kinds of forces: "Loudspeakers and microphones used in air can not transmit or receive in the water well because they usually have a 'soft' vibrating structure. This is like a soft spring (i.e., coil) with a head cap transferring its energy to a medium through this cap: in air the spring moves easily back and forth since air does not create any resistance (or 'impedance' in electrical/mechanical terms) on it; in water, however, the medium is stiffer and the spring can not move that easily. That is why the underwater transducers use 'hard' piezoelectric ceramics that have a reasonable displacement that force their energy into the water. This is called impedance matching. The better the impedance match between the transmitting medium (i.e. ceramic) and the propagation medium (i.e. water) the higher the energy transfer. This means some units might work better than others depending on the construction materials and the design technique. That is the simplest way to explain this" (bold type and italics added; Adelhelm, ITC). Hydrophones, thus, as well as underwater loudspeakers, often utilize ceramic parts to match the relatively high impedances involved with underwater sound.

Also, ITC recommended Robert J. Urick's book, Principles of Underwater Sound (1975), for further reference to impedance matching and underwater acoustic principles. Urick explains that the acoustic pressure of any sound wave will be inhibited by the impedance of the medium in which it propagates. Stresses, thus, set up in the elastic medium diminish the kinetic energy of the particles in motion that create sound (Urick 12). This phenomenon can be expressed and quantified, furthermore, by the following equation, which relates intensity (I) to the instantaneous acoustic pressure of a sound wave (p) (Urick 12):

where þ is the density of the medium in which the sound propagates and c is the speed of sound in that medium. The intensity, or power, of a sound wave is, thus, inversely related to the factor þc, called the specific acoustic resistance of the medium (Urick 12). The greater this resistance, the less intensity a particular sound will have. Since the speed of sound is nearly five times faster in water than in air (1150 ft/s in air vs. 4750 ft/s in water—reaching 5050 ft/s in some areas of salt water) and since the density of water is much greater than air, furthermore, seawater has a specific acoustic resistance of 1.5 * 105 g/cm2·s, whereas air only has a resistance of 42 g/cm2·s: this is a difference of substantial magnitude—the specific acoustic resistance being 360,000% greater in water than in air! All this boils down to is that it is much harder to make a sound underwater than in air: sound waves of equal sound pressures will have much less intensity in water because of the greater acoustic resistance, or "impedance," of the medium. (Note: impedance should not be confused with attenuation or transmission loss; though more input energy is required to initiate the propagation of sound in water, signals can travel to surprisingly long distances in some cases.)

Like ITC, Urick also relays that ceramics are used in the construction of hydrophones to better match the high impedances involved with underwater sound: "In air, other kinds of transducers are commonly used. Among these are moving-coil, moving-armature, and electrostatic types. In water, piezoelectric and magnetostrictive materials are particularly suitable because of their better impedance match to water. Ceramic materials have become increasingly popular in underwater sound because they can be readily molded into desirable shapes. Present-day sonars use ceramic transducer elements almost exclusively because of their inexpensiveness and availability" (Urick 32). Urick explains, furthermore, what is meant by piezoelectric: "[In water, the ability to transduce sound to electrical energy] rests on the peculiar properties of certain materials called piezoelectricity (and its variant, electrostriction).... Some crystalline substances, like quartz, ammonium dihydrogen phosphate (ADP), and Rochelle salt, acquire a charge between certain crystal surfaces when placed under pressure; conversely, they acquire a stress when a voltage is placed across them. These crystalline substances are said to be piezoelectric. Electrostrictive materials exhibit the same effect, but are polycrystalline ceramics that have to be properly polarized by being subjected to a high electrostatic field; examples are barium titanate and lead zirconate titanate" (Urick 31-32). It is interesting to note, furthermore, that ITC does indeed use lead zirconate titanate as the electrostrictive ceramic in their hydrophones, as specified for their basic model ITC-4066 on their website: "Constructed of Channelite-5400 lead zirconate titanate (Navy Type 1 ceramic)" (ITC).

Introduction • Main Body • Closing • Sound Samples • References • Equipment Catalog • Top

* * *Audible Transformations in Underwater Sound

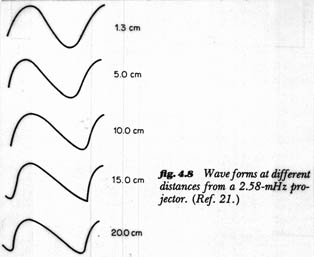

Besides hydrophone construction, Urick also addresses my other objective this quarter in trying to understand the audible transformations that sounds portray underwater. As he explains, one feature of underwater sound is that there is an irregular sound field at short distances. Unlike a point source of sound in air, the intensity of sound near a point source in water is highly variable due to reflections from the oscillating surface boundary: "In the near field the intensity at any point is the sum of contributions from different parts of the radiating surface. The sound field is therefore irregular and does not fall off smoothly with distance, as in the far field" (Urick 72; see Figure 1 below). When the surface is smooth, water forms an almost perfect reflector of sound and such irregularities do not occur; when the surface is rough, however, as it usually is to some extent, especially at sea, the surface acts rather as a scatterer, "sending incoherent energy in all directions" (Urick 129): "Large and rapid fluctuation in amplitude or intensity is produced by reflection at the sea surface... about 10 percent of the measured reflection losses of short pulses were greater by 10 dB or more above the average, and 10 percent were smaller by 3 dB or less. [...] Such fluctuations in amplitude may be attributed to reflections from wave facets on the sea surface that present a constantly changing size and inclination to the incident and reflected sound" (Urick 130). One audible effect of underwater sound, therefore, is a fluctuating amplitude.

Figure 1. Urick 72 Besides affecting the amplitude, water's scattering surface also has consequences for the frequency of a sound source underwater. Essentially, the vertical motion of the surface wave superposes itself upon the frequency of the sound incident upon it, much in the manner of frequency modulation (FM): "The moving surface produces upper and lower sidebands in the spectrum of the reflected sound that are the duplicates of the spectrum of the surface motion.... Thus, the mobile sea surface produces a frequency-smearing effect on a constant-frequency signal" (Urick 129; see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2. Urick 130 For the above diagram, Urick writes: "In (a) a sinusoidal pulse is incident on the sea surface and is reflected and scattered as a pulse of variable amplitude and frequency. Its spectrum is shown in (b) for a low and for a high sea state, and we note that energy appears to be extracted from the incident frequency centered at zero Hz and fed into upper and lower sidebands. The motional spectrum [of the sea's surface] is shown in (c). Thus, the spectrum of the surface motion appears in, and widens, the spectrum of the incident sound" (italics added; Urick 129). Besides a fluctuating amplitude, therefore, another audible effect of underwater sound is frequency-smearing.

Understanding this "frequency-smearing" effect more precisely and quantifying its behavior, furthermore, could potentially find good explanations and models for simulation in studying frequency modulation (FM) synthesis techniques in computer music: "Essentially, FM is fast vibrato. When a vibrato rate moves into the audio range, and its depth is well in excess of that generally used in vibrato, the effect - instead of being one of fast up and down repeated glissandi, sliding above and below a base frequency - is to distort the waveform of the modulated oscillator ('carrier'), producing instead what is known as 'sidebands' above and below the base frequency. Sidebands are additional spectral components which, depending on the ratio between the frequency of the carrier and the frequency of its modulation, will either form harmonic or inharmonic relationships with the base (i.e. the carrier) frequency. The positioning of sidebands is a function of the carrier:modulator ratio, and their number and amplitude vary in proportion to the amplitude of the modulator (i.e. the depth of modulation). While the precise relationship between the sidebands, and the carrier:modulator ratio and the amplitude of the modulator (modulation index), can be determined by the use of Bessel functions, in general, it is reasonable to say that the number of sidebands produced on either side of the carrier will be equal to the modulation index plus 2. Further, the position (i.e. frequency) of the sidebands will follow the basic rule: carrier-frequency ± (k * modulator-frequency) where k is the order of the sideband and generally ranges from 0 to the modulation index + 2" (Hind "FM-part 1"). Using this knowledge, the frequency and amplitude of sidebands superposed on underwater sound sources by the motion of waves at the surface could thus be calculated knowing the frequency and amplitude of the surface waves...

The complexity of the surface structure, however, which is an unpredictable superposition of many wave sources of varying amplitudes and frequencies, and the nature of musical sound sources, which, likewise, normally contain a wide range of constantly varying amplitudes and frequencies, defy the simplicity of the above considerations, which have as their basis a single, constant carrier-frequency coupled with a single, constant modulator-frequency. I envision, however, that some simplification may be made in combination with random functionality that might still mimic the dynamic complexity involved with frequency-smearing of a broadband sound source underwater. It may be noted, furthermore, that surface waves such as those found in swimming pools will not have considerable amplitude, obviously, especially compared with those of the ocean; and the modulator index, therefore, may be so low as to render sideband generation insignificant relative to the amplitude of the incident/"carrier" frequencies, and the effect of frequency-smearing may be for the most part ignored, if not entirely so.

Urick touches upon another aural consequence of water on sound that also manipulates its frequency content. He mentions that "water, with or without contaminants such as air bubbles, is to some extent nonlinear. That is, the change in density caused by a change of pressure of a sound wave in water is not linearly proportional to the change in pressure... frequencies different from the input frequency occur at the output. For sinusoidal acoustic waves, a variety of additional frequencies in water are found to be generated" (bold type and italics added; Urick 81). Urick is unfortunately vague about the reasons for such nonlinearity, however, since the topic "has little content of interest to the sonar engineer" (Urick 81). He does explain, though, that such extraneous frequencies only occur at high amplitudes, that such phenomena are thus termed finite amplitude acoustics, and that the subject of nonlinear or finite-amplitude acoustics is "theoretically complex with a rich literature" (Urick 81); he offers, thankfully, at least one title of such literature in his references for the interested engineer: I plan to, but have not yet had access to this article (McDaniel, O.H.: Harmonic Distortion of Spherical Waves in Water, J. Acoust. Soc. Am., 38:644, 1965).

One example that Urick provides, anyhow, of nonlinear frequency generation in water is that of harmonic generation. Because of nonlinearity, propagation velocity is dependent on the pressure amplitude of a sound wave, and "high positive or negative pressures travel faster than low ones" (Urick 81). I do not understand the cause of this phenomenon (Urick does not provide an explanation), but the result of it, anyway, is that "an initially sinusoidal waveform progressively steepens as it propagates, so as to eventually acquire, in the absence of dissipation, a sawtoothlike waveform having a steep beginning and a more gradually sloping tail" (Urick 81):

Figure 3. Urick 82 The important aural implication of this sawtoothlike waveform (also for reasons Urick does not state, and beyond my own comprehension at this point) is the generation of harmonics of the fundamental frequency. Urick explains, furthermore, that "this creation of harmonics occurs at the expense of the fundamental. A portion of the power in the fundamental is converted into harmonics, where it is more rapidly lost because of the greater absorption at higher frequencies. This harmonic conversion process is greater at high amplitudes than at low ones so that, as the source level increases, the harmonic content increases also. A kind of saturation effect occurs, whereby an increase of source level does not give rise to a proportional increase in the level of the fundamental frequency. This saturation effect forms [a] limitation on the use of high acoustic powers in water" (bold face and italics added; Urick 81-82). Besides fluctuating amplitude and frequency-smearing, thus, another audible effect of underwater sound is that of harmonic saturation. It should be noted again, however, that harmonic saturation is a phenomenon associated with finite amplitude acoustics and, therefore, will only take significant effect at higher amplitudes; furthermore, such amplitudes may be higher than can practically be generated by musical sources.

While FM synthesis seems suited to frequency-smearing as previously noted, additive synthesis seems like a good technique for simulating harmonic saturation on the computer. As Nicky Hind defines additive synthesis: "In additive synthesis, each partial is modeled by a separate sinusoidal oscillator, thus creating the possibility for the individual specification of amplitude and frequency (and phase), and how these will evolve over time. The output of these oscillators is summed together to produce a composite waveform" (Hind "Additive Synthesis—part 1"). Using this synthesis technique, harmonic saturation in underwater sound could be simulated by a set of partials ("partials," or harmonics, are defined as frequencies which are multiples of the fundamental pitch). These partials, also, would increase in amplitude if the amplitude of the whole was specified to increase, while the fundamental frequency of the sound source would conversely decrease in amplitude: effectively simulating the "saturation effect." How this technique could be applied to a broadband sound source of music, however, instead of to a single fundamental pitch, I do not know. This same problem, remember, has also been noted to complicate FM synthesis of frequency-smearing.

One last consideration which Urick provides in the way of audible effects is that of underwater reverberation. For the same reason we have seen earlier for amplitude fluctuations in the near field of a sound source (i.e. a sound scattering surface boundary), reverberation is heard as "an irregular, quivering, slowly decaying tone": "Within the smooth decay there appear onsets of increased reverberation whenever the emitted sound intercepts the sea surface and bottom, as well as blobs of reverberation of roughly the same duration as that of the pulse" (Urick 281). Furthermore, it has been found through field observations that "the reverberation amplitude is greater than its rms value about 37 percent of the time and less than its rms value 63 percent of the time" (Urick 282). The following is an illustration of the blobby nature of underwater reverberation:

Figure 4. Urick 283 This quivering amplitude distribution of underwater reverberation, furthermore, is probably one of the important factors missing in the convolution process I had employed last Spring for synthesizing an underwater acoustic soundscape: the impulse responses that I had recorded underwater were mostly accomplished in very still water, and, therefore, without much scattering of the signal. Without surface scattering, however, much of the characteristic effects of underwater sound are absent, including irregular reverberation amplitudes and frequency-smearing, and the aural results will be very much indistinguishable from those in air, especially at normal amplitudes where nonlinear effects of finite amplitude acoustics such as harmonic saturation do not occur significantly.

With further regards to my convolution process, since the effects of scattering at the surface manifest themselves in amplitude envelopes with blobs approximately equal in duration to that of the emitted pulse anyway, an impulse response of only a fraction of a second will not portray any audible amount of quivering even if there is a significant amount of scattering at the surface. How the reverberation would fluctuate for a continuous signal, such as that of music, as opposed to only a pulse of sound would be a valuable investigation for future synthesis technique: any pattern which presents itself in the irregularity could then be used to formulate an amplitude envelope on sound files after they have been convoluted with the underwater impulse response, thus providing the results with fluctuations that cannot be captured with the impulse response alone. This I indirectly achieved in the Spring by cross-synthesizing the convoluted sound file with a sample recording of underwater turbulence: effectively enveloping the amplitude of the original sound file with the fluctuating amplitude of the turbulence. Note, however, that such amendments to the amplitude envelope make no consideration for the effect of frequency-smearing, which is also absent in the convolution technique. I have already described how frequency modulation, by some twist of complexity, may somehow be employed to this extent.

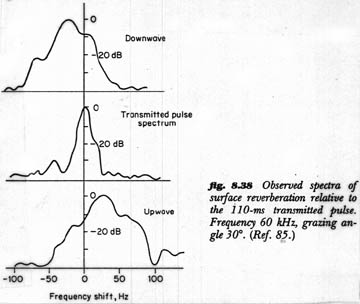

Urick also explains frequency distribution in light of reverberation. Two effects can be observed in the reverberation spectra of a sinusoidal sonar pulse transmitted underwater: (a.) a shift in center frequency and (b.) a spreading out of the frequency band, different from the aforementioned effect of frequency-smearing. The shift in center frequency of a non-moving sound source is "simply the doppler shift caused by... any uniform velocity of the reverberation-producing [surface] scatterers themselves" (bold face and italics added; Urick 282); the band spread of reverberant frequencies are also similarly doppler effects, but these are caused by the different motions of the surface scatterers within such "uniform velocities." Tidal waves, thus, would cause shifts in the center frequency of a sound, while other less uniform and less amplified surface waves cause the spreading out of the sound's frequency band. Here is a diagram which illustrates these two effects (note that the spectrum of the transmitted pulse, a simple sinusoid of 60 Hz, already includes the frequency-smearing sidebands which are a result of superpositioning with the surface wave):

Figure 5. Urick 284 Furthermore, since "the mean frequency and the spread of the frequency of reverberation are of direct concern for the design of filters to suppress reverberation" (Urick 285) in sonar applications, much is written about these topics; these sources will, of course, only make observations in light of single sinusoidal sonar pulses and be of little help to the prediction of broadband behavior—though perhaps something can be had from the simple case that can be extended to the latter; this is another question I have yet to answer. I imagine however that shifts in center frequency and spreading of frequency band could potentially be accomplished through some sort of FFT filter that dynamically attenuates and amplifies certain frequencies and frequency ranges within the spectrum of the observed sound according to parameters gathered either through field observations or through equations given in texts on sonar applications.

Introduction • Main Body • Closing • Sound Samples • References • Equipment Catalog • Top

* * *How Humans Hear Underwater

All of the considerations thus far with respect to the aural implications of sound propagation underwater describe the phenomena as they empirically exist and can be detected with a hydrophone. A different set of considerations, however, must be provided in reference to human underwater perceptions, since what we hear when we are submerged underwater is distorted by our auditory apparatus. This is important to observe for my musical objectives since the effect of an underwater concert—performing or broadcasting music for a submerged audience—would be dramatically different in aural result from that of an underwater recording.

My source of information with respect to human underwater perception is Michel Redolfi himself, who, as I have mentioned already in my introduction, is the world's first (and only?) underwater musician and has been putting on underwater concerts for the past fifteen years or so since his work at UCSD in coordination with the Scripps Institute of Oceanography. He kindly forwarded me an interview translated from German between himself and the Festival ARS ELECTRONICA which was held in September of 1996 with regards to "scientific research aspects and psychoacoustic related effects" of underwater music. From this interview, I have learned that the most important thing to understand with regards to human underwater listening is that our ears are mostly useless; this occurs for the same reason that a normal microphone does not function well underwater—as has been previously described, there is a poor impedance match between the construction materials of the auditory device and the propagation medium: "In the water, the audience picks up the sound only by the effect of bone conduction. Basic principles: In immersion, the ear drum (tympani) is too close to the density of the water to stop any sound wave (the ear drum is made of 90% water). Only the bones are hard enough to stop the fast sound waves (1450 m/s, four times the speed of sound in the air). So, the bones from the neck and skull resonate and carry the vibrations simultaneously to both of the inner ears, the nerves' endings located in the skull" (bold face and italics added; Redolfi). Thus, much in the way that hard ceramics are used to perceive displacements in hydrophones, humans must rely on the hard material of the skull for aural perception.

One result of bone conduction is that the skull provides only one source of transmission instead of two as with the ears. Stereo reception, therefore, is not possible and sounds will consequently lack direction cues. Since the human observer is the vibrating apparatus, however, the reception is not that of a mono signal but of a signal coming from all directions at once: "A listener in the water doesn't hear in stereo so he loses his sense of direction, [and] Cartesian space (Left-Right/Up-Down) dissolves. Space is not 'mono,' but omniphonic (sounds seem to be coming from all around). Psycho-acoustically, this loss of Cartesian space translates in one's mind as an inner vibration that would come from inside the body... Interpretation of this feeling varies depending on people's beliefs, fantasies, and poetic feelings..." (Redolfi).

Another result of bone conduction is low-end filtering of the underwater sound spectrum: "Thanks to bone conduction, a radical filtering operates on the sounds that we listen to in the water. The bone equalization brings an emphasis on medium to high frequencies, while basses are completely ignored. The underwater sound world appears very crisp, crystal-like" (Redolfi).

Also, the underwater soundscape that we hear as a result of bone conduction is remarkably pure, or "hi-fi," as noises from the air do not transfer below the water surface and since underwater noises are generally not strong enough to resonate the skull: "While we have our head in contact with sonic waters, our bone conduction apparatus doesn't pick up air noises, nor water background noises as they are not strong enough to resonate in the body. In a pool those unheard noises are actually generated by pumps; at sea by boat propellers, wave foam, etc... Also, the listeners in the water are not generating any concert hall body noises such as coughing, sneezing, talking, shuffling clothes, turning program pages, clapping hands, etc. The only thing you hear in the water is a pure signal as if you were listening with headphones. This very close encounter with the soundscape was called 'HI-FI' by Murray Shafer, the Canadian musicologist and composer who conceived the theory of Soundscapes back in the seventies. He was referring to Hi-Fi natural soundscapes such as the ones of remote mountains or deserts. Lo-Fi in comparison applies to street soundscapes... I would say also to concert halls!" (Redolfi).

One last effect of bone conduction is that you cannot stop listening simply by "closing your ears" (i.e. forcing something in the ear canal such as ear-plugs or a finger); the ears are not responsible for what you hear underwater—rather, "closing your ears" would require some mechanism of stopping your skull from being vibrated by the underwater sound waves: as, for instance, getting your head back into the air (Redolfi).

In sum, while bringing an audience into the water provides an enhanced hi-fi, omniphonic listening experience, filtering of lower-end frequencies will deprive the dynamic range of the sound and stereo effects cannot be achieved. Furthermore, the safety issues involved with carrying on voltages in an immerged public (for underwater loudspeakers and other underwater electronic sound devices) are considerable, while equipment is not cheap, and the technical difficulties involved with getting a good sound take years of experience and massaging to overcome: Michel Redolfi's underwater engineer for many years, Dan Harris, related this to me over the phone. Whether or not acoustic musical instruments can produce high enough levels for bone conduction to occur, also, is doubtful: putting my jazz combo in the deep end of a pool would, thus, provide little else than an effective mute. Whether or not such acoustic levels could be recognized by a hydrophone, however, I still need to find out.

Introduction • Main Body • Closing • Sound Samples • References • Equipment Catalog • Top

Closing

What I have learned about underwater sound this quarter in a nutshell are the following concepts: impedance matching, fluctuating amplitude and blobby reverberation, frequency-smearing, harmonic saturation at high amplitudes, doppler effects that shift the center frequency and spread the frequency band, and the results of bone conduction for human underwater perception. As previously related, furthermore, in the absence of sound scattering the recorded signal will not sound much different from that produced in air. Making recordings of music in a pool, thus, will have minimal aesthetic interest. Recordings in the ocean, however, where rough waves do provide significant scattering effects, will be plagued by high levels of ambient noise, much in the way an old phonograph recording sounds like in comparison to a digital audio recording: "The average level of ambient sea noise is about 10 or 15 dB above 1 microbar (i.e. up to +15 dBµb), which would be roughly comparable to a busy office with typewriters clattering, papers rustling, people walking and talking, and telephones ringing [due to] wave motion on the surface, friction of moving water currents against the bottom and against each other, the noise of shipping traffic, and, superimposed on all that, noises of marine animals. The activity of marine animals alone may add as much as 20 dB to the ambient noise level. This marine animal noise is often in frequency ranges that can interfere with sonar gear, acoustic mines, and underwater listening equipment" (Tavolga 4-5). What would be ideal, thus, for potentially interesting underwater music recordings is a large, rough body of water with low ambient noise: say, something you might find at a water park on its off hours. Such an environment would also have to be deep enough to prevent excessive amounts of surface interference: "[Surface reflection] is an image source of practically equal intensity, but opposite phase. The source and its image will produce practically zero intensity just within the surface. The closer the source to the surface the greater the region of interference. This suggests... the desirability of using a source at some distance below the surface..." (Stewart 232). Finding a water park with a pool of sufficient depth might be possible, but experimenting with more extreme depths, of course, won't be.

All of these physical obstacles, coupled with the high cost and maintenance of underwater sound equipment, loudly suggest an effort at computer synthesis if the aural results of an ideal underwater environment—fluctuating amplitude, frequency-smearing, harmonic generation, and doppler effects—are desired. I propose that a simple case could be tested to this end, simulating the aforementioned effects on the computer using a single-frequency signal that could be manipulated with amplitude envelopes, frequency modulation, additive synthesis, and FFT filters in the various ways described in this paper; precision could be acquired, furthermore, if desired, through the use of sonar equations that accurately predict the parameters to include in these manipulations. From these experiments, lessons learned could be forwarded to more advanced sound sources such as live or pre-recorded music.

~end~

Introduction • Main Body • Closing • Sound Samples • References • Equipment Catalog • Top

Sound Samples

The following sound files provide examples of the work I have done thus far to synthesize an underwater sound environment. Each is programmed in Common Lisp Music (CLM). The first file is a whale-like song that I synthesized using a single-frequency sound source. To the original sound clip, I successively add filters and other techniques for an increasingly realistic underwater effect. The second file fittingly uses these techniques on a recording of "Water Music," one of composer George Frideric Handel's (1685-1759) famous orchestral suites. At first, this is made to sound as though broadcast pool-side from a boom-box until, whoops!, the stereo is dropped (thrown?) into the water. This rendition is thus dubbed, "(Under-)Water Music."

- whale_synthesis.mp3 (1:02)

- (under)_water_music.mp3 (1:35)

Introduction • Main Body • Closing • Sound Samples • References • Equipment Catalog • Top

References

- Adelhelm, Clifford G., Sales Administrator for the International Transducer Corp. (ITC), Santa Barbara, CA. e-mail correspondence, Mon, 26 Jan 1998.

- Etter, Paul C. Underwater Acoustic Modeling. 2nd ed. (London; E & FN Spon, 1996).

- Hind, Nicky. Common Lisp Music (CLM) Tutorials. http://ccrma.stanford.edu/software/clm/compmus/clm-tutorials/toc.html.

- Harris, Daniel. phone correspondence.

- International Transducer Corporation (ITC). http://www.itc-transducers.com.

- Jensen, Finn B. Computational Ocean Acoustics (Woodbury, NY: American Institute of Physics, 1993).

- Moore, F. Richard. Elements of Computer Music (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, c1990).

- Redolfi, Michel. Sonic Waters (sound recording) (Therwil, Switzerland; New York, NY: Hat Hut, p1984).

- Redolfi, Michel. Michel Redolfi & Underwater Music = Scientific Research Aspects and Psychoacoustic Related Effects (press interview). trans. German. (Festival ARS Electronica, Sept 1996); received from Redolfi through e-mail correspondence, Fri, 27 Feb 1998.

- Stewart, George Walter. Acoustics (New York, D. Van Nostrand company, inc., 1930).

- Tavolga, William N. Review of Marine Bio-Acoustics (Port Washington, N.Y.: U.S. Naval Training Device Center, 1965).

- Urick, Robert J. Principles of Underwater Sound. 3rd ed. (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1983).

©1998, john a. maurer iv