The Leslie, named after its inventor, Don Leslie,10is a popular audio processor used with electronic organs and other instruments [#!Bode84!#,#!Henricksen81!#]. It employs a rotating horn and rotating speaker port to ``choralize'' the sound. Since the horn rotates within a cabinet, the listener hears multiple reflections at different Doppler shifts, giving a kind of chorus effect. Additionally, the Leslie amplifier distorts at high volumes, producing a pleasing ``growl'' highly prized by keyboard players.

The Leslie consists primarily of a rotating horn and a rotating speaker port inside a wooden cabinet enclosure [#!Henricksen81!#]. We first consider the rotating horn.

Rotating Horn Simulation

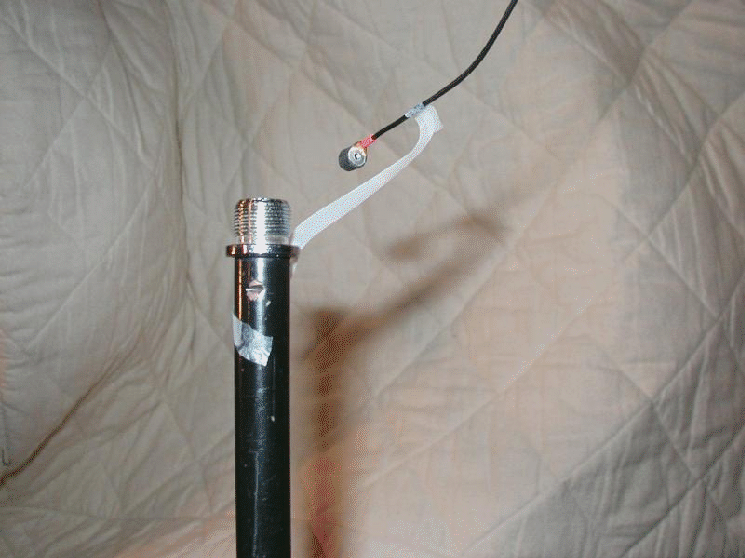

The heart of the Leslie effect is a rotating horn loudspeaker. The

rotating horn from a Model 600 Leslie can be seen mounted on a

microphone stand in Fig. ![]() . Two horns are apparent, but

one is a dummy, serving mainly to cancel the centrifugal force of the

other during rotation. The Model 44W horn is identical to that of the

Model 600, and evidently standard across all Leslie models

[#!Henricksen81!#]. For a circularly rotating horn, the source

position can be approximated as

. Two horns are apparent, but

one is a dummy, serving mainly to cancel the centrifugal force of the

other during rotation. The Model 44W horn is identical to that of the

Model 600, and evidently standard across all Leslie models

[#!Henricksen81!#]. For a circularly rotating horn, the source

position can be approximated as

By Eq.![]() (7), the source velocity for the circularly rotating horn is

(7), the source velocity for the circularly rotating horn is

Note that the source velocity vector is always orthogonal to the source position vector, as indicated in Fig. 1.1.

Since

![]() and

and

![]() are orthogonal,

the projected source velocity Eq.

are orthogonal,

the projected source velocity Eq.![]() (8) simplifies to

(8) simplifies to

Leslie Free-Field Horn Measurements

The free-field radiation pattern of a Model 600 Leslie rotating horn

was measured using the experimental set-up shown in

Fig. ![]() [#!SmithEtAlDAFx02!#]. A matched pair of Panasonic microphone elements

(Crystal River Snapshot system) were used to measure the horn response

both in the plane of rotation and along the axis of rotation (where no

Doppler shift or radiation pattern variation is expected). The

microphones were mounted on separate boom microphone stands, as shown

in the figure. A close-up of the plane-of-rotation mic is shown in

Fig.

[#!SmithEtAlDAFx02!#]. A matched pair of Panasonic microphone elements

(Crystal River Snapshot system) were used to measure the horn response

both in the plane of rotation and along the axis of rotation (where no

Doppler shift or radiation pattern variation is expected). The

microphones were mounted on separate boom microphone stands, as shown

in the figure. A close-up of the plane-of-rotation mic is shown in

Fig. ![]() .

.

The horn was set manually to fixed angles from -180 to 180 degrees in increments of 15 degrees, and at each angle the impulse response was measured using 2048-long Golay-code pairs [#!FosterGolay!#].

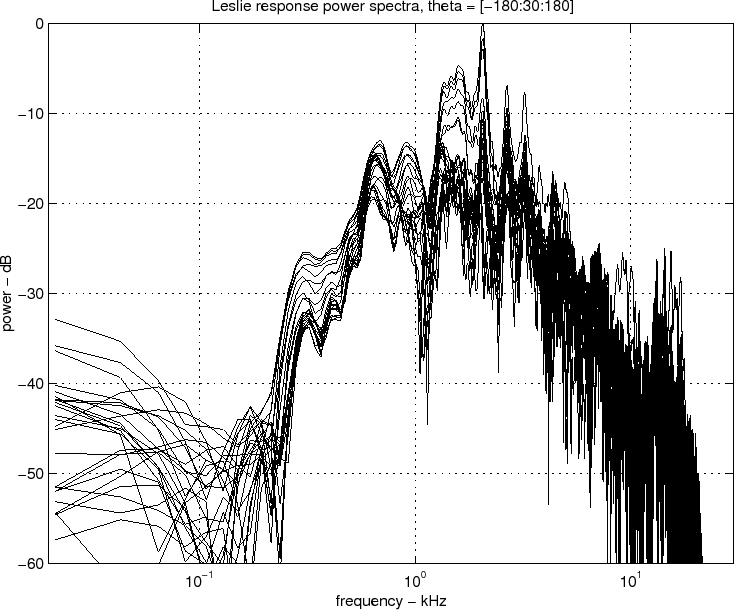

Figure ![]() shows the measured impulse responses and Fig.

shows the measured impulse responses and Fig. ![]() shows the corresponding amplitude responses at the various angles.

Note that the beginning of each impulse response contains a fixed

portion which does not depend significantly on the angle. This is

thought to be due to ``leakage'' from the base of the horn. It

arrives first since the straight-line path from the enclosed speaker

to the microphone is shorter than that traveling through the horn

assembly.

shows the corresponding amplitude responses at the various angles.

Note that the beginning of each impulse response contains a fixed

portion which does not depend significantly on the angle. This is

thought to be due to ``leakage'' from the base of the horn. It

arrives first since the straight-line path from the enclosed speaker

to the microphone is shorter than that traveling through the horn

assembly.

Separating Horn Output from Base Leakage

Note that Fig. ![]() indicates the existence of fixed and

angle-dependent components in the measured impulse responses.

An iterative algorithm was developed to model the two components

separately [#!SmithEtAlDAFx02!#].

indicates the existence of fixed and

angle-dependent components in the measured impulse responses.

An iterative algorithm was developed to model the two components

separately [#!SmithEtAlDAFx02!#].

Let ![]() denote the number of impulse-response samples in each

measured impulse response,and let

denote the number of impulse-response samples in each

measured impulse response,and let ![]() denote the number of angles

(-180:15:180) at which impulse-response measurements were

taken. We denote the

denote the number of angles

(-180:15:180) at which impulse-response measurements were

taken. We denote the ![]() impulse-response matrix by

impulse-response matrix by

![]() .

Each column of

.

Each column of

![]() is an impulse response at some horn angle.

(Figure

is an impulse response at some horn angle.

(Figure ![]() can be interpreted as a plot of the transpose of

can be interpreted as a plot of the transpose of

![]() .)

.)

We model

![]() as

as

Each column of the matrix

![]() contains a copy of the estimated

horn-base leakage impulse-response:

contains a copy of the estimated

horn-base leakage impulse-response:

The estimated angle-dependent impulse-responses in

![]() are modeled as

linear combinations of

are modeled as

linear combinations of ![]() fixed impulse responses, viewed

(loosely) as principal components:

fixed impulse responses, viewed

(loosely) as principal components:

To start the separation algorithm,

![]()

![]() is initialized to the

zero-shifted impulse response data

is initialized to the

zero-shifted impulse response data

![]() diag

diag![]() , ignoring

the tails of the base-leakage they may contain. Then

, ignoring

the tails of the base-leakage they may contain. Then

![]()

![]() is

estimated as the mean of

is

estimated as the mean of

![]()

![]()

![]() diag

diag![]() . This

mean is then subtracted from

. This

mean is then subtracted from

![]() to produce

to produce

![]()

![]()

![]() diag

diag![]() which is then then converted to

which is then then converted to

![]()

![]() by a truncated SVD. A revised

base-leakage estimate

by a truncated SVD. A revised

base-leakage estimate

![]()

![]() is then formed as

is then formed as

![]()

![]()

![]() diag

diag![]() , and so on, until convergence is

achieved.

, and so on, until convergence is

achieved.

Results

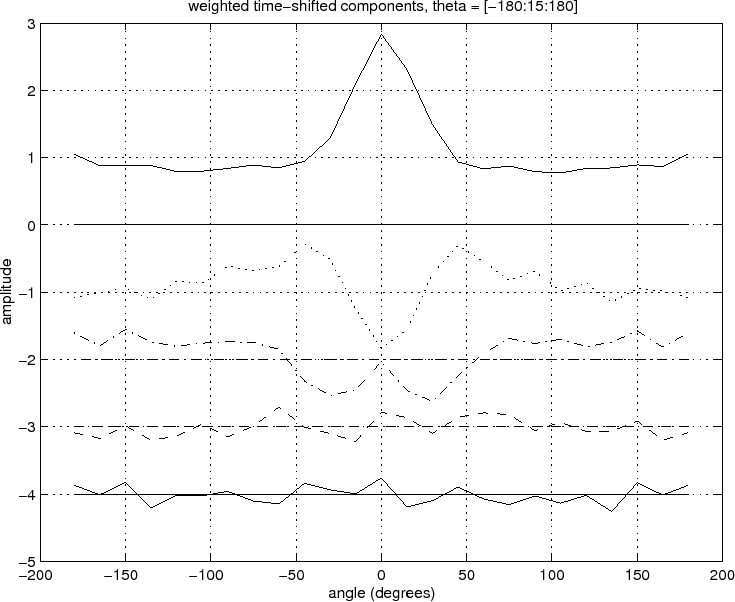

Figure ![]() plots the

plots the ![]() weighted principal components identified for the

angle-dependent component of the horn radiativity. Each component is

weighted by its corresponding singular value, thus visually indicating

its importance. Also plotted using the same line type are the

zero-lines for each principal component. Note in particular that the

first (largest) principal component is entirely positive.

weighted principal components identified for the

angle-dependent component of the horn radiativity. Each component is

weighted by its corresponding singular value, thus visually indicating

its importance. Also plotted using the same line type are the

zero-lines for each principal component. Note in particular that the

first (largest) principal component is entirely positive.

Figure ![]() shows the complete horn impulse-response model

(

shows the complete horn impulse-response model

(

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() diag

diag![]() ), overlaid with the

original raw data

), overlaid with the

original raw data

![]() . We see that both the fixed base-leakage

and the angle-dependent horn-output response are closely followed by

the fitted model.

. We see that both the fixed base-leakage

and the angle-dependent horn-output response are closely followed by

the fitted model.

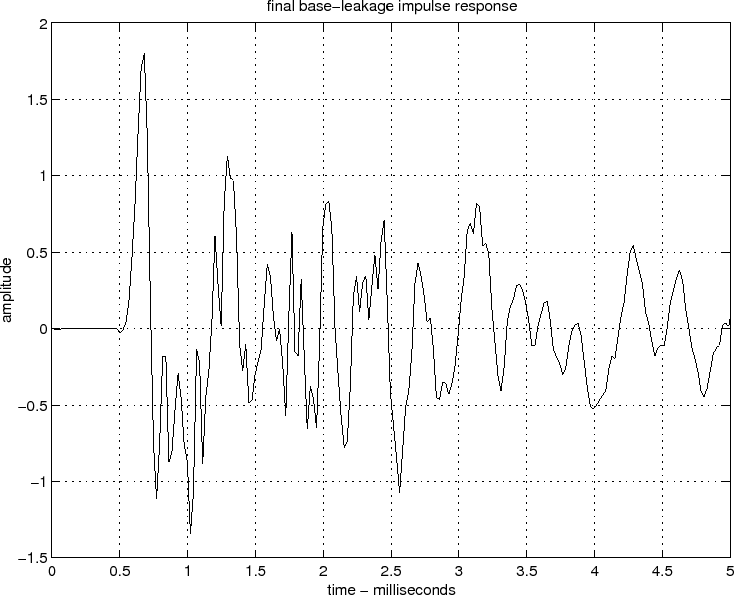

Figure ![]() shows the estimated impulse response of the base-leakage

component

shows the estimated impulse response of the base-leakage

component

![]() , and Fig.

, and Fig. ![]() shows the modeled angle-dependent

horn-output components

shows the modeled angle-dependent

horn-output components

![]() delayed out to their natural arrival

times.

delayed out to their natural arrival

times.

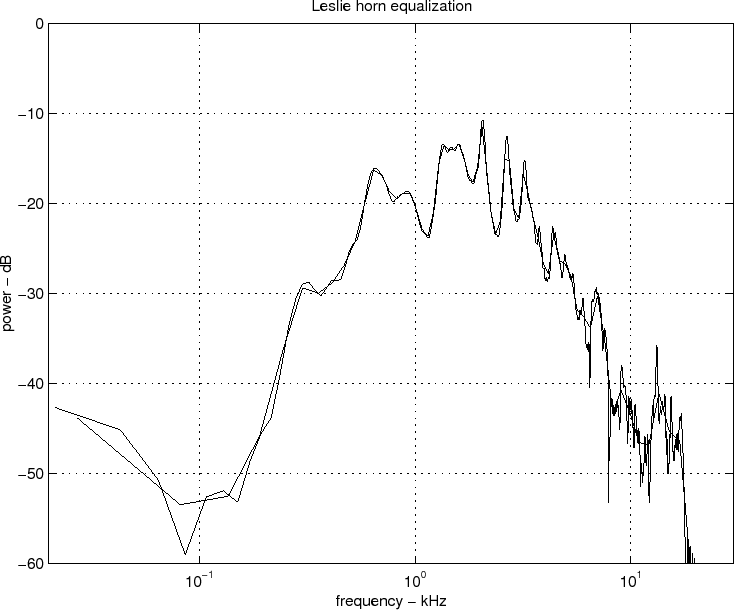

Figure ![]() shows the average power response of the horn outputs.

Also overlaid in that figure is the average response smoothed

according to Bark frequency resolution [#!SmithAndAbel99!#]. This

equalizer then becomes

shows the average power response of the horn outputs.

Also overlaid in that figure is the average response smoothed

according to Bark frequency resolution [#!SmithAndAbel99!#]. This

equalizer then becomes ![]() in Fig. 1.1. The filters

in Fig. 1.1. The filters

![]() and

and ![]() in Fig. 1.1 are obtained by dividing

the Bark-smoothed frequency-response at each angle by

in Fig. 1.1 are obtained by dividing

the Bark-smoothed frequency-response at each angle by ![]() and

designing a low-order recursive filter to provide that equalization

dynamically as a function of horn angle. The impulse-response arrival

times

and

designing a low-order recursive filter to provide that equalization

dynamically as a function of horn angle. The impulse-response arrival

times ![]() determine where in the delay lines the filter-outputs

are to be summed in Fig. 1.1.

determine where in the delay lines the filter-outputs

are to be summed in Fig. 1.1.

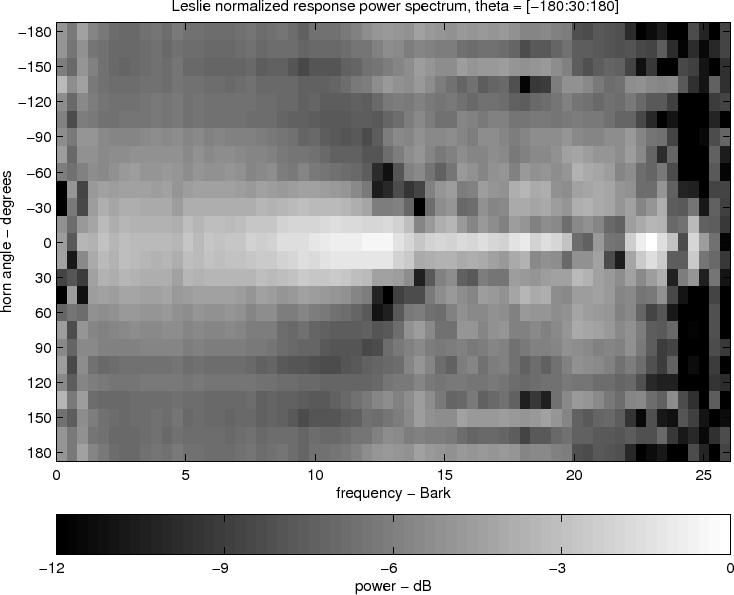

Figure ![]() shows a spectrogram view of the angle-dependent

amplitude responses of the horn with

shows a spectrogram view of the angle-dependent

amplitude responses of the horn with ![]() (Bark-smoothed curve in

Fig.

(Bark-smoothed curve in

Fig. ![]() ) divided out. This angle-dependent, differential

equalization is used to design the filters

) divided out. This angle-dependent, differential

equalization is used to design the filters ![]() and

and ![]() in Fig. 1.1. Note that below 12 Barks or so, the angle-dependence

is primarily to decrease amplitude as the horn points away from the

listener, with high frequencies decreasing somewhat faster with angle than low

frequencies.

in Fig. 1.1. Note that below 12 Barks or so, the angle-dependence

is primarily to decrease amplitude as the horn points away from the

listener, with high frequencies decreasing somewhat faster with angle than low

frequencies.