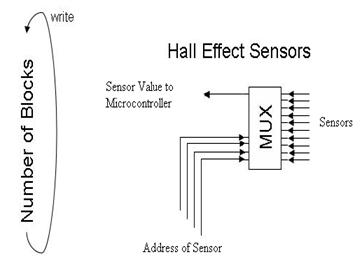

As seen in the figure to the left, to handle the large input/output sensing scheme, however, numerous multiplexers are used to map multiple Hall Effect sensors onto a single analog-to-digital pin on the microcontroller (totaling four A/D pins for the 64 continuous sensors). Similarly, multiplexers are also used for the LED output control, sending a simple voltage on/off signal.

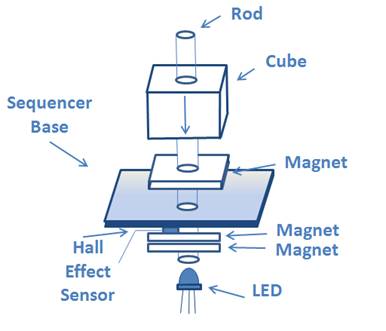

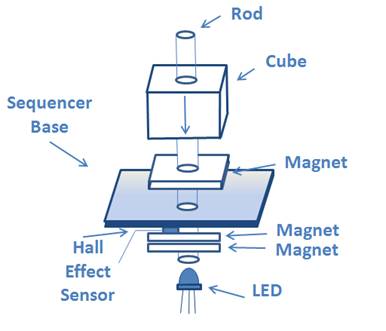

From the analog-to-digital conversion of the continuous sensor voltage levels, a maximum-likelihood threshold estimation is used to resolve the number of blocks/rod (i.e. 0, 1, 2, or 3). Large variability in sensors and magnet strength require an initial calibration phase, measuring the mean displacement per number of cubes. Once calibrated, the sequencer enters a ready state mode and begins to sample the sensor data and establish two-way communication to a personal computer.

The necessary information is then sent to Pd via OSC into a sequencer patch. The sequencer patch synchronizes the commands on light and sound to a beats per minute (BPM) rate and quantization ratio controlled by the user (the baseline quantization count is sent to the microcontroller at the respective tempo). Additionally, OSC message data rate is reduced for maximum performance by only sending changes in the number of block.