A Comparison of Free Jazz to 20th-Century Classical Music

similar precepts and musical innovations

©

February 24, 1998

Table of Contents:

Introduction

The term "free jazz"—coined in 1964 from an Ornette Coleman recording to describe the "new thing" developing in jazz at that time—is even today little understood by jazz musicians and the music community at large. This may be due in large part to the fact that jazz, in general, is very often slighted as lacking in intellectual depth and does not usually receive the same critical analysis granted to the more "serious" art forms. It may also be due to the fact, of course, that improvisation—one of the foundations of jazz—defies traditional analysis in that it is not written out and that not too many scholars are willing to make the extra effort to transcribe music where necessary and to tackle the difficulties inherent in analyzing music based solely on recordings. At the same time, jazz musicians and jazz critics themselves pay little attention to free jazz, as most do not approve of its untraditional techniques to this day and would rather have it not considered jazz at all; rather, they see it as the anti-jazz (Jost 31). Everything that the traditional jazz musician has practiced years to accomplish and prides himself on, afterall—improvising over chord changes and crafting harmonic complexity, etc.—is suddenly often considered void and a large waste of time. Thus, banished by its own kind and ignored by scholars of serious music, free jazz is something of an orphan in the music community.

A few scholars and critics do take free jazz into their hands, however, and I am very happy to have found the English translation of Ekkehard Jost's Austrian publication of 1974: Free Jazz. Jost, a professor of musicology at the University of Giessen in Germany and president of jazz and new music institutes in Hessen and Darmstadt, does well to address the issues of analyzing an improvisatory art form, cautioning the reader of its drawbacks while also asserting its validity. Not only is the book full of Jost's own precisely notated transcriptions of musical excerpts from a large discography of free jazz recordings, different electro-acoustic measurements made by the author at the State Institute of Musical Research in Berlin also support his claims where appropriate.

To begin with a very general definition of free jazz, then, the only universal "rule" of the style is "a negation of traditional norms" (Jost 9)—whether it be in harmonic-metrical patterns, the regulative force of the beat, or in structural ideas. Just as 20th-century classical music extends and separates itself from the tonal language of traditional classical music, so too free jazz "frees" itself from the conventions of functional tonality: "In traditional jazz, the primary purpose of the theme or tune is to provide a harmonic and metrical framework as a basis for improvisation. In free jazz, which does not observe fixed patterns of bars or functional harmony, this purpose no longer exists" (Jost 153). As the "free" in "free jazz" implies freedom from functional tonality and traditional norms, therefore, contemporary classical music, I think, could likewise be aptly labeled "free classical." Both genres, at least, rest on similar precepts.

The absence of a common language in 20th-century classical music and free jazz leads, furthermore, to an inherent "variability of formative principles," the consequence of which is that "specific principles are tied up with specific musicians and groups": "Rudolph Stephan, speaking with reference to avantgarde music in Europe (1969), drew attention to the absorption of the 'musically universal' by the 'musically particular.' This is true of free jazz too..." (Jost 10). General tendencies and trends in either free jazz or 20th-century classical composition, thus, can only be recognized after thorough analysis and investigation of its constituent parties: "They exhibited such heterogeneous formative principles that any reduction to a common denominator was bound to be an oversimplification" (Jost 10). This could be a major factor for the fuzziness surrounding free jazz (and 20th-century classical music for that matter, especially outside of academia) as it does not lend itself to very concise explanations or definitions. Traditional: that is what free jazz is not; but as for what free jazz is, one can only answer with respect to individual styles and to general trends. For this reason, Jost divides his analysis into ten chapters—each one dedicated to an important free jazz pioneer or group: John Coltrane (two chapters), Charles Mingus, Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, Archie Shepp, Albert Ayler, Don Cherry, the Chicagoans, and Sun Ra.

As well as to its wide variability, a significant factor responsible for the misunderstanding surrounding free jazz, I think, lies in people's misinterpretation of "free." As I have just shown, what "free" does mean in free jazz is "free from tradition" (or, more accurately: "free from functional harmony"); however, this freedom does not in any way further imply that free jazz is "free from everything," or a freedom to do anything. Americans became "free" from Great Britain in 1776, for example, but they did not also become "free" from law: they gained independence from foreign political rule so as to establish their own rules, as realized in the Constitution. So too it is true that free jazz had gained independence from "foreign rules"—i.e. functional tonality—so as to establish their own formative principles (Jost 13). What is not at work in free jazz, note, is anarchy or unbounded emotionality, as many confuse it to be. Recently, I even read an online hypertext version of an educator's tutorial on jazz improvisation that made the following misleading assertion with regards to free jazz: "There are many different approaches to free playing, but by its very nature, there are no rules" (italics added). This statement falsely insinuates that free jazz means "free from everything." The same tutorial goes on to claim that when playing free music in a solo setting, "you have complete freedom to change the directions of the music at any time, and are accountable only to yourself". On the contrary, free jazz is an intensely communicative—as opposed to self-absorbed—musical genre in which "the members of a group are forced to listen to each other with intensified concentration" (Jost 23) and in which meaning is created through interaction and not just merely through individual expression or a group of such self-operating individuals.

Neither free jazz nor 20th-century classical music is aimless, then, though often the innocent listener, bred only on traditional music and, thus, listening for things not present in these genres, sometimes cannot understand or hear, therefore, the principles at work behind the music and find it "weird," "senseless," or "bad" sounding. Such criticisms are rather "symptomatic of free jazz as a whole" and stem from the fact that these listeners fail to observe that "divergent formative principles... demand to be heard in various ways" (Jost 119): or in other words, don't compare apples with oranges—free jazz isn't traditional jazz and it shouldn't be judged or analyzed according to the same criteria. To steal a line from Joel Lester, with reference to analyzing 20th-century music, "to approach a composition with an open mind, ready to discover what the composer has in store for us, is a safer procedure than to assume in advance that any particular pattern will be in evidence" (Lester 73). "Formative principles are in fact present" in free jazz, much in the same ways that they exist in 20th-century classical music, as we will see, and improvisation in free jazz "is not just left to pure chance": "Analysing a piece that consists simply of accidental sound coincidences would have as little value as trying to calculate the probability of winning or losing in a game of dice where everybody has an equal chance" (Jost 13).

The comparison between free jazz and concepts of 20th-century classical music, though not investigated in any depth by the author of Free Jazz, is indeed often suggested by Jost himself: "The influences felt in the divergent personal styles of the Sixties encompass musicians like Sidney Bechet, Ben Webster, Thelonious Monk and Lennie Tristano as well as Stravinsky, Schoenberg and Cage" (italics added; Jost 11), though he often makes the reservation that such similarities are not direct influences: "It would be highly unlikely that anyone would seriously call Sidney Bechet or John Cage 'pioneers' of free jazz" (Jost 11), and: "The appearance of [Cecil Taylor's] kind of 'collective composition,' at the time that aleatoric techniques were on the rise in European New Music, is surely a coincidence" (italics added; Jost 76). It is shown sometimes, however, that a few of the pioneers in free jazz did study or have a knowledgeable background in 20th-century classical music: Cecil Taylor studied for three years at the New England Conservatory, for example, where he came into contact with the works of Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern, and was especially interested in Bartók and Stravinsky (Jost 66); and Anthony Braxton had made detailed studies of John Cage and Karlheinz Stockhausen (Jost 167).

Whether the similarities between the two genres are consequences of each other or not, however, a comparison between them does seem to suggest itself rather loudly. My goal is simply to make the comparison more explicit, using my knowledge of 20th-century classical music and examples that I have heard and studied, to function as sort of a companion essay to the text of Free Jazz itself: an "appendix," say. Such a comparison is thought to be good since it brings together the concepts presented in Free Jazz in an organized manner and can help make the unknown more familiar through association, legitimizing, hopefully, the genre of free jazz to those of music academia unfamiliar with the genre or prejudiced against it, while also hopefully inspiring readers to explore the genre further in their own listening and study.

Before taking a closer look at the similarities, however, I think it is valuable that I first give a quick glance at what the fundamental differences between free jazz and 20th-century classical music are, so as not to confuse the ensuing comparison with an equation. What creates the boundary between jazz and classical music? One obvious difference, already touched upon, is the method of creation: whereas classical musicians put their ideas into written scores—even when utilizing chance processes, free jazz musicians create primarily through improvisation. Another segregating factor between free jazz and 20th-century classical music are their rhythmic characters: "The decisive criterion [of jazz music]—as always—is the rhythmic substance, which despite freedom from tempo and absence of recognizable accentuation patterns [as often can be found in free jazz] still has that psycho-physically sensible kinetic energy that corresponds, however remotely, to the phenomenon of swing" (Jost 198). Thus, in free jazz—whether directly accentuated or indirectly implied by periodic swells of dynamic and texture—there is always a sense of pulse that underlies the music.

These boundaries, of course, are not always clear cut, and sometimes the genres can become rather indistinguishable. This can occur, for instance, when all rhythmic substance is abandoned in free jazz: "When even an intimation of a common rhythmic basis is dispensed with, kinetic energy is totally reduced and there is a subjective indeterminacy, like that occasionally encountered in serial music... " (re: Cecil Taylor; Jost 73). Another way that boundaries can become fuzzy is when the methods of creation in either genre are combined, as in the music of Cecil Taylor, which often possesses a "fusion of constructive planning and improvisatory creativity" (Jost 77) and in the "spontaneous composition" of Don Cherry, which derives its improvisation mostly on pre-constructed thematic catalogues. This sort of fusion can also be found in the classical spectrum in the spontaneous compositions of Luigi Nono and others involved in advanced European improvised music.

My plan of attack in comparing the concepts of free jazz with 20th-century classical music will first entail an analysis of the methods through which either genre extends and abandons the tonal language and its functional harmonies. Next, the different means of expression in free jazz utilized in the absence of functional tonality will then be considered, followed by an analysis of the new approaches to overall formal structure used to encapsulate these means of expression—which, as is also often true of 20th-century composition, are merely extensions of traditional forms. Lastly, I will show how asymmetry and disjunctedness—prevalent tendencies in many aspects of 20th-century classical music—are also characteristic of free jazz in various ways, and how the use of parody, too, is a prominent feature to both genres.

Introduction • Main Body • Closing • References • Top

Main Body

Contents:

- Abandoning functional tonality

- New means of expression

- Formal structures

- Asymmetry and disjunctedness

- The use of parody

* * *Abandoning Functional Tonality

"The emancipation from traditional jazz laws first significantly infiltrated that area of jazz where the restrictions had become most noticeable, i.e. in functional harmony" (Jost 18).

The origins of jazz have their foundation on simple harmonic progressions, mostly in patterns like I-IV-V-I as in the blues or in the fundamental II-V7-I. Any beginning course in jazz theory will start out with these functional relationships; as evident, for example, in the first three volumes of the very popular Jamey Aebersold "play-a-long" book and recording sets: volume 2 is Nothin' But Blues, about which is stated: "The Blues have had the very essence of the jazz sound since the 1920's" (Aebersold 3), and volume 3 is The II/V7/I Progression, which asserts in bold-faced type: "Probably the most important musical sequence in modern jazz! A must for all aspiring jazz players" (Aebersold 3).

Just as classical music began adding complexity to its functional relationships, however, by delaying the arrival at harmonic goals through increased usage of secondary dominants and deceptive cadences and by replacing traditional chords with new voicings such as the augmented sixth chord, so too in jazz one encounters a trend of increasing harmonic complexity, especially since the 1950s with the advent of bebop and hard bop. This is evident in the use of tritone substitution—replacing the V7 with a chord a tritone away; upper structures or "polychords"—placing different harmonies on top of traditional ones; deceptive cadences; what has become known as the "Trane changes," after John Coltrane—which delay the resolution of the traditional II-V7-I with closely related secondary V-I cadences; as well as many other new harmonic conventions that one can study in the various available contemporary jazz theory texts. Figure 1 gives a good portrayal of how the original harmonic foundations of the blues, for example, have become increasingly complex through such devices.

Complexity in classical music would eventually reach a point where it began extending the boundaries of its tonal language, as in Wagner's "Tristan," which delays resolution in the piece to an extent that no clear tonic is ever established, paving the way for gradual developments in the direction of atonality and the 12-tone system. So too in jazz, harmonic complexity led to innovations which eventually escaped the conventions of functional tonality. Harmonic tricks such as tritone substitution and "Trane changes" began to stale, and jazz musicians as early as the late '50s began to look for different ways of expressing themselves: "The upheaval we are going to discuss took place at a time when the functional harmonic models were worn out as a basis for improvisation; when the constant reinterpretation of chord patterns, although increasingly complex, appeared with inexorable regularity during a piece and led more frequently to clichés, from which even the most inspired improvisers could not escape" (Jost 18). Just as in early 20th-century classical music, furthermore, jazz musicians began thinking, thus, more horizontally—in terms of melodic variation—instead of in terms of chords and chord changes. With regards to this new emphasis, Miles Davis once remarked: "I think that there is a return in jazz to emphasis on melodic rather than harmonic variation. There will be fewer chords but infinite possibilities as to what to do with them. Of course, several classical composers have been writing this way for years. Too much modern jazz has become thick with chords" (Jost 21).

The first extension of functional harmony in jazz that I will discuss, therefore, is Miles Davis' use of modes, first evident in his composition "Milestones" from the record of that title in 1958: "Like the musical language of medieval Europe, modal playing in jazz uses scales whose structure does not necessarily correspond to our familiar major and minor scales" (Jost 18). These modes did not necessarily arise with direct reference to the tradition of early European church modes, but are, nevertheless, the same modes of antiquity: Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, and Locrian. With the use of modes, functional harmony no longer dictates musical progress (just as it does not in 16th-century counterpoint), and the use of one or two modes in a piece, rather, define the material from which the musician improvises. "Milestones," for example, is divided into two sections: the first of which is based on the Dorian mode on G; the second on the Aeolian mode on A (see Figure 2 below): "What was first regarded [by jazz critics] as a total weakness in harmony, was in reality aiming at a new concept of improvisatory creation" (Jost 18). Just as Wagner's "Tristan" paved the way for non-tonal music in 20th-century classical music, so too modal playing in jazz was a first step in the direction of non-tonal free jazz.

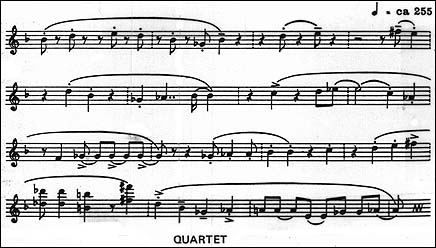

Figure 2. Jost 26 John Coltrane, though originally an innovator of hard bop and a pioneer of new harmonic possibilities (the "Trane changes"), eventually collaborated with Miles Davis and shared the practice of modal improvisation, as on the 1959 recording Kind of Blue ("So What" and "Flamenco Sketches" are modal). Coltrane, however, further developed modality in his own later recordings. He began introducing a large degree of chromaticism to his use of modes which, as evident in his improvisation on "My Favorite Things," expands the material by introducing foreign tones at exposed points in his musical phrasings (see Figure 3 below). Such conscious use of chromaticism intentionally extends the tonal framework much in the way of early 20th-century classical composers, as, for example, the way Schoenberg consciously uses dissonance in his "Prelude III."

Figure 3. Jost 26 A year or so later, on "India," modal treatment in Coltrane's improvisation is even freer than on "My Favorite Things," and he begins to display mode-mixture, as in Figure 4 below, which shows flats despite the established G Mixolydian mode, creating a bitonality with the pianist's chord progressions. On the classical side of things, such bitonality is well exemplified in Bartók's "Forty-Four Violin Duets: No. 33, Song of the Harvest," as apparent in the opposing key signatures between the two violins throughout the piece. Free use of mode mixture as in "India" can also be found in many classical pieces, as for example in Bartók's "Stars, Shine Brightly," which, though in the key of F minor, has many unflattened sonorities that suggest a major quality. This can also be found in Bartók's "Courting Song," from his "Four Hungarian Folk Tunes," which shifts between A minor and A major sonorities.

Figure 4. Jost 29 In "India," Coltrane further extends his use of chromaticism to the point that he begins to play "around the mode more than in it" and the modal framework begins to breakdown: "No longer does the modal material bind the whole piece together; instead, it functions as a starting and landing point for melodic excursions, which are just one step removed from polytonality" (Jost 31). This is similar in effect, I believe, to Webern's "Sechs Bagatellen für Streichquartett," which, though not constructed according to the 12-tone system, consciously avoid a tonal center or a focus on any particular key. In Coltrane's musical development, then, we see that chromaticism plays an increasingly important role, until tonality—as established already rather loosely in modal improvisation—is almost completely dissoluted.

Another approach to handling pitch was achieved by Ornette Coleman, who, rather than create a modal framework, established a "tonal centre" for his compositions and improvisations: "His point of reference is not [chord] changes but a kind of fundamental sound, for whose focal tone the term 'tonal centre' was coined" (Jost 48). As in Coleman's composition "Tears Inside," for instance, in Figure 5, "the tonal centre D flat... is valid for the whole piece, not just for the blues segments normally in the tonic (i.e. bars 1-4, 7-8 and 11-12). It acts like an imaginary pedal point: Coleman's melodies proceed from it, are oriented toward it, and it is even present subliminally when seemingly cancelled by dissonant intervals" (Jost 48). This procedure was also a feature of Archie Shepp's music. In the classical domain the concept of a "tonal centre," sometimes referred to as a "focal pitch" or focal point, is also a feature of several composers. In the third movement of Schoenberg's "Serenade, op. 24," for example, Bb acts as a focal pitch, as Lester explains: "Although Bb is a focal pitch as registral center of the diverging and converging registral limits, it is by no means a 'tonic' in the tonal sense. The melody may be centered around Bb, but it is not in 'Bb major' or 'Bb minor.' Eleven of the twelve pitch-classes are present... preventing the clear statement of any diatonic scale" (Lester 75). Similarly, the treatment of pitches in "Tears Inside" is extremely non-diatonic (i.e. chromatic), and all twelve pitch-classes can be found in the first two choruses alone, though Db presides. Another good example of a focal pitch in 20th-century classical music is that of Bartók's first movement in "Music for Strings, Percussion and Celeste" which expands and contracts in register to and from an A pitch.

Since modality and tonal centers still worked to treat specific pitches, these approaches to pitch could still be considered as fundamentally tonal (though, surely, not in the traditional sense of functional harmony); Cecil Taylor's music, however, often approaches atonality: "One of the most prominent features of Taylor's playing was a harmonic language in which functional relationships are, if not abandoned, at least heavily veiled... he jeopardized the functional identity of his chords by their very density" (Jost 74). Such an approach is similar to the use of coloristic chords in the impressionistic music of Debussy; for example, in his "Prelude VI" ("Triste et lent"): chords still work to treat a tonality, here, but they are used and voiced for their color, rather than for their function. This use of coloristic chords can also be found in Schoenberg's "Prelude VI" ("Sehr langsam"), where the voicings can become rather dense like in Taylor, as in m.8 when the two hands play seven tones together, including two more while these are tied over. Cecil Taylor later progressed from "harmonic density," also, to the use of clusters: "A cluster can be defined as a pile or stack of tones, created by simultaneously striking all or most of the chromatic steps within a certain area" (Jost 74). These clusters, which Taylor used as "short, sharp tone-blocks hammered in extremely rapid succession" and in a "percussive nature" (Jost 74) immediately draw association with the rhythmic dissonances also prevalent in the piano music of Béla Bartók: "Free Variation" and "Syncopation" being two obvious examples, where percussive clusters of usually two or three notes occur frequently .

One last treatment of pitch in free jazz in the absence of functional tonality can be found in the music led by Don Cherry. Rather than use traditional modes as the basis for his improvisations, as in the music of Davis and Coltrane, Cherry defines new modes according to the pitches present in the themes of his compositions, especially in Symphony for Improvisers and in Complete Communion: "...what the players primarily improvise on are not tonal centres, modes or even chord patterns, but the themes themselves and their motivic substance... the tonal basis is not represented by a scale which the tune follows and on which the improvisations are built; instead, the melody is itself the basis" (Jost 145). Thus, Cherry employs a "specific kind of modality which only rarely coincides with the scales commonly used in jazz" (Jost 148). The only example I can think of which is similar in 20th-century classical music is Olivier Messiaen, who also defined a "specific kind of modality" in his "modes of limited transposition," as can be read about thoroughly in Messiaen's Technique of My Musical Language: "...their impossibility of transposition makes their strange charm. They are at once in the atmosphere of several tonalities, without polytonality, the composer being free to give predominance to one of the tonalities or to leave the tonal impression unsettled" (Messiaen 58). So too in Cherry's thematic modality, the improviser is free to emphasize different tonalities within the mode or to abandon tonality entirely: the performer may employ "changing tonal centres which have a logical connection with the thematic structure" or, at times, completely abandon the modal frame of reference (Jost 146).

Introduction • Main Body • Closing • References • Top

* * *New Means of Expression

In the face of these new methods of pitch handling in free jazz, musicians were faced with the problem of avoiding stagnation. Since the systems which free jazz created no longer defined forward motion in terms of functional harmony, new methods were needed to give progression to its musical ideas. In Jost's survey of techniques, it can be observed that primarily three different techniques were used: motivic chain associations (the manipulation, development, and interaction of melodic patterns), timbric variation (playing with different sounds), and the use of other musical parameters besides pitch or timbre to create distinctions (i.e. rhythm, tempo, meter, dynamic, etc.). These techniques are similar to those employed in 20th-century classical music, furthermore, where anything capable of making a distinction can be utilized and where parameters other than pitch often take precedence in creating forward motion.

With regards to 20th-century classical music, first off, Lester asserts that "since there is no pitch language shared to all nontonal pieces, motives in nontonal music play an essential role in determining the pitches of the piece" (Lester chp. 1). This is especially apparent in Bartók's music, where the manipulation of patterns, or motives, often dictate the progress of a composition. "From the Diary of a Fly," for example (Mikrokosmos VI, no. 142), can be seen to progress from the beginning as a motive (m.1-2) which is repeated in quasi-"ostinato" fashion, varying in different ways and combinations throughout the piece (transposition, registral shift, rhythmic manipulation, interval expansion and contraction, fragmentation and sequence, articulation change, inversion, retrograde, etc.): similar, say, to how something is put together piece by piece on an assembly line—except that at any time it may also be taken apart. This method of expression is also taken up by Ornette Coleman in free jazz, who "overcomes the monotonous tendency of a tonal centre" though motivic improvisation (Jost 48): "Coleman invents, as he goes along, motives independent of the theme and continues to develop them... one idea grows from another, is reformulated, and leads to yet another new idea. For this procedure, which is of the utmost importance for the understanding of Coleman's playing, we would like to introduce the term motivic chain association" (Jost 49).

Like Bartók, furthermore, Coleman "does not limit his motivic associations to phrases that follow one another directly, but takes up ideas that are, so to speak, several links back in the chain, and creates larger contexts in this way" (Jost 50). This can be also found in "From the Diary of a Fly" in m.26, for example, which ends the previous string of events and returns instead to the opening material in m.1-2 (transposed down a whole step). Examples of motivic chain association in Coleman's playing are presented and explained in Figure 5. Don Cherry is another musician in free jazz who mostly utilized motivic substance, though, as previously explained, emphasizing thematic material with his motives rather than tonal centers alone.

Opposed to Ornette Coleman's melodic variation and motivic manipulation are players in free jazz who create distinctions rather through a-melodic, or timbric, variation. Cecil Taylor, for example, "compensated stagnating motion [with] kinetic impulses... based on the rise and fall of energy" (Jost 70-71) (see Figure 6 below). Thus "energy," rather than motives, creates the forward motion, and this is achieved in Taylor's music through a combination of timbric variation and swells in dynamic, forming oscillations through registral motion, harmonic density, and increased loudness. Thus a "school" of free jazz musicians was founded—the "energy-sound players" (Jost 71)—which focused primarily on timbre as a parameter for musical expression. Similarly, in Stravinsky's "Symphonies of Wind Instruments," different timbres, or instrumentations, (along with different tempos) are most striking in characterizing different ideas juxtaposed within the piece.

Figure 6. Jost 70 A slightly different slant on energy-sound playing in free jazz is presented by Coltrane in Ascension, who by this time had abandoned functional harmony as well as modal improvisation. His goal now was only in creating different sound-structures and tone-colors through collective improvisation: "In the collective improvisations of [Ornette Coleman's] Free Jazz, the contributions of each and every improviser have a certain melodic life of their own; motivic connections and dove-tailing of the various parts create a polyphonic web of interactions. In Ascension, on the other hand, the parts contribute above all to the formation of changing sound-structures, in which the individual usually has only a secondary importance. Quite plainly, the central idea is not to produce a network of interwoven independent melodic lines, but dense sound complexes" (Jost 89). These "dense sound complexes," furthermore, are created much in the same way that Ligeti, in classical music, creates sound masses: "When seven independent melodic-rhythmic lines coincide, the relationships between them lose clarity, fusing into a field of sound enlivened by irregular accentuations" (re: Coltrane; Jost 89). Ligeti labels the method "micro-polyphony" (creating a large sound mass through many individual melodic lines), and it can be studied in compositions of his like "Lontano" or "String Quartet."

Another approach to energy-sound playing in free jazz can be found in the example of the Chicagoans—the "Chicagoans" is the label Jost uses to include the free jazz musicians of Chicago's Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (AACM) and the Art Ensemble of Chicago. Like Coltrane in Ascension, the main emphasis of the Chicagoans was on collective interaction. Their approach to evolving sound structures, however, abandoned all rhythmic motion and rhythmic articulation so that each player was contributing mostly sustained tones to the overall sound-mass as opposed to individual melodic lines. This is not aptly described as micro-polyphony, thus, but does however have a correlation in the classical realm in the example of Schoenberg's expressionistic "Summer Morning by a Lake," amongst others, in which the music is similarly "given differentiation by instrumental shadings and dynamic gradations, and by a diffuse internal motion" (Jost 169) and has no audible rhythmic content.

A last experiment of timbre occurs in the manner of introducing unconventional instrumental techniques, unusual instruments, and unusual sound combinations. As Jost points out, such experimentation is characteristic of the Chicagoans and the music of Sun Ra: "The Art Ensemble [of Chicago] expands the tone-colour aspect of its music by bringing in a multitude of new instruments. Gudrun Endress (1970) reports that when the group went to Europe it took more than 500 musical instruments along" (Jost 177); and similarly, "the [Sun Ra] Arkestra soloists become increasingly multi-instrumental" (Jost 187). Roscoe Mitchell alone, for example, of the Art Ensemble of Chicago, plays soprano, alto and bass saxophone, clarinet, flute, cymbals, gongs, conga drums, steel drum, logs, bells, siren, and whistles (Jost 177)! Even the accordion is sometimes present in the Art Ensemble, and Sun Ra even uses different synthesizer sounds from his Moog electronic keyboard. Unusual instrumentations are also present in 20th-century classical music, as, for example, the use of a musical saw and electric guitar in Lukas Foss' "Paradigm." Electronic instruments were also explored for their new sound, as with Messiaen's use of the Onde Martenot in his "Turangalila Symphonie." Jost makes the point, furthermore, that free jazz, like 20th-century classical music, employs its exploration with new sounds not aimlessly, but in purposeful ways: "It is important to note that these and other examples of sound alienation... very rarely appear for their own sake in the Art Ensemble. That is, the denatured sound is not to be comprehended as an isolated occurrence sufficient unto itself; in general, it stands in a dialectical relationship to the music around it" (Jost 178).

Other musicians, of course, combined the techniques of energy-sound playing with motivic chain associations, or juxtaposed the two. Archie Shepp, for one, employs motivic connections, but these are often disrupted by or strung together with timbric explorations, as with his unique "staccatoed legato" articulation of the saxophone (see Figure 7 below) and with slurred tones—"in which whole sequences of tones are glissandoed" and the only definable pitches are at the beginning and the end (Jost 107). This is also a feature of Albert Ayler's music, who juxtaposed clearly melodic phrases with a-melodic sound-spans and growled "bent" tones. Ornette Coleman, as well, possessed a certain degree of energy-sound playing, in which he utilized "wrong intonation" of tones to create syntactic organization: through different breath pressures and "false fingering" of the alto saxophone Coleman was able to shift the overtone complexes of a note to match the expressive quality that he wanted out of it: an F in "Peace," for example, would have a slight deviation in frequency from an F in "Sadness," as the emotional content is different for either piece (Jost 53). Combination of motivic manipulation with timbric variation is very well exemplified in 20th-century classical composition in the "Sequenzas" of Berio, in which clearly melodic motifs are interspersed with extended techniques and unusual sounds of various traditional instruments.

Figure 7. Jost 107 Outside of motivic and timbric development musicians in free jazz also create forward motion through other musical parameters. In the music of Charles Mingus and Sun Ra, for example, changes in dynamic, tempo, meter, and rhythm are all important variables in the movement of a piece, similar to how ideas are delineated in Stravinsky's "Symphonies of Wind Instruments." Rhythmic motives, furthermore, often dominate the progression of ideas in Sun Ra's music (Jost 192), similar to the way pulse is used to make distinctions in Stravinsky's "The Rite of Spring," or the way Steve Reich composes pieces entirely for percussion. Changing meters, as present in Mingus' music (Jost 40), is also a feature of "The Rite of Spring" and much of Bartók (see Figure 8). One of Albert Ayler's characteristic formative means, furthermore, is a "high degree of dynamic differentiation": "Ayler begins phrases (or sound-spans) fortissimo and then lets them subside gradually to pianissimo, until they end in whispered tones that are barely audible" (Jost 127) (see Figure 9), and Cecil Taylor also, as we have seen, employs dynamic gradations to avoid stagnation. Dynamic, too, is a major means of expression in Bartók's "Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celeste," as there is a striking motion from soft to loud and back to soft; and changes in dynamic also work to give direction to the first of Webern's "Sechs Bagatellen," since other musical parameters—pitch, rhythm, register, articulation, and timbre—are constantly and rapidly changing without perceptible pattern. Lastly, Cecil Taylor often creates motion through changes in register: he would play clusters "like arpeggios and covering several piano registers" (Jost 74). In the classical sense, Ruth Crawford's third movement of her "String Quartet" also employs register for direction: starting in a narrow register, expanding to a climax, and then returning to the original narrow register.

Introduction • Main Body • Closing • References • Top

* * *Formal Structures

Changing our perspective, now, from means of expression within pieces to overall structures at work in free jazz, we find again a similar variability of strategy. At the simplest level, some musicians, like Ornette Coleman, choose to retain the traditional formal structures of jazz: even though he ignores their traditional harmonic implications (replacing them with tonal centers), he often employs very traditional frameworks (A-A-B-A or 12-bar blues) even dividing his solos into obvious periods as in the blues (see arrows in Figure 5) and excepting the common procedure of "theme-improvisation-theme" (Jost 47-49). Similarly, Charles Mingus "accepts the old formal patterns, but alters them by filling them with new content" (Jost 39); he uses traditional 16 and 32-bar forms and 12-bar blues "again and again" but breaks away from the "conventional formula of 'theme-improvisation-theme'" in jazz by employing total collective improvisation in his ensembles (Jost 39). Like Coleman and Mingus, Shepp too has an "ambition to play a kind of music unburdened by traditional constraints and yet retaining to a great extent the essence of older jazz styles" (Jost 107), which he accomplishes through utilizing traditional frameworks to organize his energy-sound playing and motivic developments; and Sun Ra retains the structure of the blues as an "empty formula": "The four and twelve-bar caesuras are observed in phrasing and in change of soloist. But apart from that, the harmonies on which the blues are usually based are often ignored and replaced by modal levels or tonal centres" (Jost 186). Coltrane and Miles Davis also employed traditional A-A-B-A song patterns for some of their modal pieces, even though "there is no functional harmonic movement at all" and "the functional relationship between the periods is avoided" (Jost 21).

Filling traditional forms with new content is also a common practice of 20th-century classical music. One example is Bartók's fourth "String Quartet" which, developing according to a process rather than harmonic development, possesses a familiar ABA sonata form, since the opening material audibly returns at the end. A loose interpretation of the sonata form is also well illustrated by Schoenberg's "Klavierstücke, op. 33a" in which the piece also returns to the beginning motive at the end though it is composed according to the 12-tone system and using different articulations to realize distinctions.

Another formal strategy common to both free jazz and 20th-century classical music is to use traditional forms in some new innovative way, or to use traditional forms for providing structure but not necessarily as an audible effect. This is evident, for example, in the unique way Coltrane uses the traditional "call-and-response" technique of early blues and jazz improvisation and of the work-chants of African-American slaves: "In all of Coltrane's pieces, there is at one time or another a passage in which he strings together a quick succession of related phrases, two, and sometimes three octaves apart.... These 'dialogues'—an ingredient, incidentally, of Cecil Taylor's piano playing and later often used by Archie Shepp—hark back to one of the most traditional elements of jazz, however new and strange it may appear in Coltrane's music. They are highly compressed, logogram call-and-response patterns" (Jost 100) (see Figure 11 below).

Figure 11. Jost 101 Webern similarly uses old techniques for structural control in disguised ways as in his 12-tone piece "Variationen II," which, however "new and strange" sounding, employs canon for imitation between the hands (disguised by the proximity of the imitation and the speed at which the piece is played): this piece, furthermore, it is interesting to note, has a similar quality to Coltrane's "self-dialogues" in that it strings together notes which are several octaves apart. Like Coltrane, Albert Ayler also uses a disguised implementation of the call-and-response mechanism, which he achieves, instead, through his unique method of dynamic differentiation. Looking back to Figure 9, one can see a "distinct periodicity of phrasing" which is "distantly reminiscent of the call-and-response patterns of early jazz" (Jost 127). Also, just as Coltrane's "self-dialogues" are compressed forms of call-and response patterns, so too compression is a means of varying traditional forms in 20th-century classical music: take, for example, Schoenberg's "Prelude II," in which things are done only once or twice throughout the piece, giving only glimpses of phrases and extremely brief musical statements.

Besides using and varying traditional forms, free jazz also replaced them in some instances with entirely new kinds of formal structures. These new forms, furthermore, took on four general guises, all of which have good comparisons in 20th-century classical music: (a.) programmatic designs, (b.) aleatoric structures, (c.) the use of "process," and (d.) music that is non-goal-oriented, or "static."

First off, "program music" entails compositions that are intended to depict or suggest definite instances, scenes, or images; also sometimes referred to as "tone-paintings" or "expressionism." In such compositions the primary motive is, thus, to musically describe the instance, scene, or image in focus, and musical structure and other musical parameters may be molded as necessary to meet this end, not necessarily abiding by traditional forms and certainly not restrained to them. This can be well illustrated in Schoenberg's "Preludes," for example, which act as "character pieces," each displaying through various expressive means a different emotional quality. A wide contrast of emotional content can also be found in Schoenberg's "Klavierstüke, op. 33a" which similarly employs a wide range of musical parameters to support an intense "expressionism." Schoenberg's "Summer Morning by a Lake," furthermore, another example of program music, employs slow morphs in instrumental color to depict the scene which the title suggests. In free jazz one can also find extra-musical concepts guiding musical expression in the music of Sun Ra: "Sun Ra has always been concerned with translating an idea into music, illustrating an emotional state, or sketching a picture.... The motto expressed in the title of a piece directly intervenes in the process of improvisatory creation" (Jost 188). This can be heard, for example, in Sun Ra's "Outer Nothingness" which translates the "emptiness" of outer-space into a musical context by "coupling two expressive ideas: a strong emphasis on the low instrumental register, and tonal and rhythmic indeterminacy" (Jost 188) (see Figure 12).

Though not labeled as such, free jazz musicians also employ "aleatoric" structures, much in the way of 20th-century classical music, using sounds to be chosen indeterminately by the performer or left to chance. This can be found, for instance, in Coleman's collective improvisation on Free Jazz which has fixed passages that members of the ensemble perform asynchronously: "...here the players are provided with tonal material whose timing is not fixed, a procedure which was to be highly important as a composition technique in the later development of free jazz" (Jost 59). This style of controlled chance can also be found in the classical spectrum in Witold Lutoslawski's "Venitian Games" or his "Paroles Tissées," each which similarly provide different parts which are specifically notated but do not provide a fixed relationship between each other, creating a blurry aural effect. Coleman also displays aleatoric techniques in his use of trumpet and violin, neither of which he knew how to play in a traditional way and used instead as "sound-tools"—producers of sounds, rhythms and emotions without necessarily tonal content: "Whereas the overriding impression of Coleman's alto is of his conscious control of the instrument and the improvisation, that of his violin (and to a lesser extent his trumpet) is of the abdication of conscious control, and a reliance on pure chance" (Jost 65). Such a conscious "abdication of conscious control" is likewise the strategy of John Cage in his "Freeman Etudes," which uses the arbitrary pattern of star charts for the material of its musical content in an attempt to remove the composer from the very process of composition itself and to objectify the composer's position with relation to his music. Boulez made similar efforts to remove himself from the decision-making process by designating row formations for every musical parameter in "Structures."

The use of process, a prevalent practice of 20th-century classical composition, is also a formal innovation in a lot of free jazz. This can be best exemplified, I think, in the music of Don Cherry on Mu I. Here, the formal structure is determined by a process which gradually progresses through a series of pre-established themes; he creates a thematic "catalogue": "a list of alternatives to be chosen from during a concert or recording; that is, they are used when and where it occurs to Cherry to use them. Spontaneously deciding to pick a theme from that catalogue at a given time and in a given musical context, is itself an act of improvisation. Cherry improvises not on his themes, but with them" (Jost 154). The themes in Cherry's catalogues often "consist of short, rhythmically and melodically clear-cut patterns" which he "repeats several times in ostinato fashion" gradually evolving variants or proceeding to different themes (Jost 154). This process is similar, I think, to the use of process in Franco Donatoni's "Lumen," which possesses a certain "mechanical" quality about it: each part has a very simple "clear-cut pattern" which is repeated as an ostinato and evolves until it ultimately becomes something else which is also very simple and defined. Such gradual evolution of clearly defined ostinatos is also a prominent feature of a lot of Messiaen's work: for example in each of the different parts throughout "Quatuor Pour La Fin Du Temps" and in each of the two pianos in "Amen de la Création" ("Visions de L'Amen, mvmt. 1").

Another new process introduced to free jazz, similar to Cherry's process of gradual evolution, is that of continuous variation, or "A-through-Z composed" music. This can be found in Sun Ra's later music which "usually leads away from the theme": "'Pieces of a traditional kind, with a beginning and an end, occur only very rarely... On the records discussed here 'pieces' are usually the work of the sound engineer, who intervenes in a continuously evolving process of musical creation" (Jost 194). Schoenberg's "Prelude III" is similarly "through composed," continually varying in content and ending differently from how it began.

One last new formal design used in free jazz is that of non-goal-oriented, or "static," improvisation. A good example of this can be found in the "endless melodies" employed in Don Cherry's music: "These themes usually manage without any harmonic development whatever (there is often a drone as a foundation); they have hardly any rhythmic differentiation, and their melodic lay-out is cyclic" (Jost 157)(see Figure 13 below).

Figure 13. Jost 157 These "endless melodies" are important in free jazz in that "they create a new attitude toward time. For what happens are not developmental processes, in which time is filled and articulated by a variety of changing occurrences; the laws of dynamic impetus do not apply; there is a meditative lack of motion, a situation of repose in which movement is reduced to cycles of the smallest possible dimensions. The role of time consists only of its passing" (Jost 158). This practice can also often be found in the music of John Cage, as in his orchestra piece "101" which, by Eastern influence, similarly displays a meditative lack of motion. The Chicagoans are also often meditative in feel and possess an element of "psychical tranquility," since, as I have pointed out in their creation of sound-masses with long sustained sounds, there is an inherent "lack of intensity" to some their music (Jost 169). A similar sense of static motion can be found in Coleman's Free Jazz, even though the players interact through motivic chain associations, since "only rarely do emotional climaxes occur, and there is hardly any differentiation of expression": "Coleman set out to create a statical, homogeneous whole, his main point being the integration of individual ideas to form an interlocking collective" (Jost 60).

A unique combination of traditional forms with new processes, furthermore, presents itself in the music of Albert Ayler: "The source of [Ayler's] difference is the coupling of radicality with a regression to the simplest musical forms" (Jost 124). In his improvisations one can often find a direct juxtaposition of "archaic melodiousness" with his "playing what could be called waves of overblown tones that have no definite pitch, but appear as contours or sound-spans"; his music possess "an occasionally weird mixture of folksong cheerfulness and pathos" (Jost 124). Clichés and traditional jazz "riffs" are contrasted and interspersed with distorted sounds and dissonant non-tonal playing that makes for a tense dialectic in Ayler's music between sanity and insanity, tradition and revolution. A very good example of this in 20th-century classical music is Berio's "Sinfonia," in which large swells of dissonance counter things which are very tonal sounding, like the third movement of Mahler's second symphony, the skeleton of which is quoted as a backdrop. Another example is John Zorn's "Forbidden Fruit," which quotes very classical/tonal sounding excerpts (Beethoven amongst them), directly juxtaposing them with excerpts which are distorted by tape techniques or with extended techniques of the violin, creating a sort of "counterpoint" of different styles, similar to contrasts in Ayler's music.

Introduction • Main Body • Closing • References • Top

* * *Asymmetry and Disjunctedness

From formative principles to formal structures to just about every other musical parameter at work in free jazz, furthermore, a prominent feature is the use of asymmetry and disjunctedness. The juxtaposition of disjunct elements and the creation of a sense of unbalance are also, of course, very prevalent factors in much of classical music in the 20th-century. In reading Jost's Free Jazz I found that pioneers of free jazz made such innovations especially in the following categories: (a.) in the way they phrased things, (b.) in the musical content of these phrases, (c.) in rhythm, (d.) form, and (e.) in texture, all of which have good comparisons in 20th-century classical composition.

First, in terms of phrasing, Coltrane began ignoring traditionally observed patterns of phrasing in My Favorite Things, blurring the symmetrical divisions that they usually followed: "...here he plays across the patterns set up by the rhythm section, mostly ignoring the four or eight-bar units they create" (Jost 26). Coleman uses a different method of phrasing which likewise disrupts traditional divisions: "After playing a series of eighth notes on the beat, Coleman often introduces new patterns, just as simple, but plays them off-beat, creating a strong feeling of tension" (Jost 55) (see Figure 14). A good example of playing against the beat can also be found in Stravinsky's "Firebird Suite," which likewise obscures the barline divisions by playing off-beat and employing notes that are tied over from one measure to the next (see Figure 15 below).

Figure 15. source unknown Another method of phrasing which creates a sense of unbalance in free jazz can be found in the collective ensembles of Charles Mingus, in which unmatched ostinatos often occur between the musicians: "Occasionally, rhythmic patterns are fixed which turn up again and again as ostnatos in the collective choruses; shifted, placed one against the other, they give the music a dogged, screwdriver quality" (Jost 41). This same "dogged, screwdriver quality" can also be found, for example, in Bartók's "From the Diary of a Fly" (Mikrokosmos, vol. VI, no. 142), m.76-87, which matches an ostinato of eight tones in the right hand with an ostinato of only six tones in the left, creating phrases which are, thus, out of phase.

The musical content of phrases in free jazz are also often subjected to asymmetrical leanings. Coleman, for instance, has a "habit of leaving motives 'open,' of stopping just short of the goal for which he is heading and placing a dash — instead of an exclamation mark" (Jost 50), as can be seen in "Tears Inside" (see Figure 5) in bars 2 and 9 of chorus 2, which end phrases from Db (the tonal center) to neighboring tones. Archie Shepp's creation of slurred sound-blocks in his energy-sound style of improvisation, furthermore, often occur as "vehement bursts of one or two seconds at a constant fortissimo [that] break off abruptly" (Jost 117) (see Figure 16), leaving the phrases open-ended for linkage with new motives derived from them. More importantly than Shepp's sound-blocks, however, is his melodic material: of which "the melodic flow is broken into atoms" (italics added; Jost 108) (see Figure 17 below).

Figure 17. Jost 108 This construction of phrases through fragments is well exemplified in 20th-century classical music by Webern's "Sechs Bagatellen" in which musical flow is also broken up into several isolated rhythmic identities, and dynamic markings as well as articulation and register are highly variable from one fragment to the next in each of the four voices: this method being labeled "klangfarbenmelodie," or "sound color melody." Albert Ayler, also, like Shepp, often displays "a pronounced discontinuity of phrasing, a result of (1) short flourishes, (2) single staccato tones, and (3) wide leaps" (Jost 123), and, it is interesting to note, a look at a transcription of one of Ayler's improvisations (see Figure 18 below) looks very similar in character to the "sound color melody" of the Webern "Bagatelles."

Figure 18. Jost 123 Rhythm is another musical parameter which free jazz often manipulates in asymmetrical ways. Besides playing phrases off the beat, Coleman, for example, likes to employ asymmetrical accentuation patterns to blur the metrical divisions that define the music: "A similar way of heightening tension is Coleman's practice of subdividing lines of eighth notes into alternating groups of three, four, or five notes, by shifts of accent arising from the melody... what we see is not different superimposed rhythms—i.e., three against two or five against four—but an even eighth-note motion, accentuated in a way that runs counter to the metre" (Jost 55) (see Figure 19 below).

Figure 19. Jost 155 A good example of this in 20th-century classical music can be found in Stravinsky's "The Rite of Spring," which, as Figure 20 shows below, also irregularly accentuates a constant eighth-note pulse.

Figure 20. source unknown The bassists on Coltrane's India similarly create a process of "rhythmic disorientation" by bringing in "two-bar rhythmic patterns whose accent distribution often jeopardizes the fundamental rhythm" (see Figure 21 below) which "vary throughout the piece, therefore constantly giving new impulses to the rhythmic flow, and admittedly contributing to the listener's insecurity" (Jost 30).

Figure 21. Jost 30 Another method of creating rhythmic disjunctedness in free jazz is in the use of ameter, which can be heard at times in the music of Cecil Taylor and Albert Ayler. Cecil Taylor had started using drummers in 1961 who developed "urgent, dynamic chains of impulses... largely negating metre," and this metrically free rhythm became a "continuous source of energy" for Taylor's energy-sound playing (Jost 72); likewise, "Ayler's negation of fixed pitches finds a counterpart in [his drummers'] negation of the beat. In no group at this time is so little heard of a steady beat, as in the trio and quartet recordings of the Ayler group [in 1964]. The absolute rhythmic freedom frequently leads to action on three independent rhythmic planes" (Jost 128). The concept of ametric meter, or atonal rhythm, is also used in 20th-century music. In such music, the notated meter is more of a framework for the performer than a description of a perceived meter. Ameter can be experienced in the opening section of Stravinsky's "The Rite of Spring," and in much of Webern's "Sechs Bagatellen," where the music, as I have previously noted, is composed of irregular rhythmic fragments. Also, Ligeti's concept of "micro-polyphony," in "Lontano," for example—similar to Webern's concept of layered fragments—also lends itself to an ametric sound mass.

Formal structures in free jazz also sometimes display asymmetry as we have already seen in the case of continual variance in the music of Sun Ra, which, like through-composed classical music, ends differently from how it begins and does not create repeated divisions as in traditional forms (AABA, ABA, etc.). A really good example of asymmetrical form can also be found in Ornette Coleman's composition "Mind and Time": "A division of the melody into bars (which at the same time implies an accentuation of certain beats) is irrelevant; since the tune is 11 and 1/2 'bars' long, notes falling on 'one' the first time round would fall on 'three' in the repeat" (Jost 57) (see Figure 22 below).

Figure 22. Jost 57 Formal structure is also rendered disjunct by the inclusion of various heterogeneous themes into a single composition, which can be found in the music of Archie Shepp: "Almost without exception, Shepp's compositions for his studio groups are like suites in which various (and sometimes extremely heterogeneous) means of expression are opposed and intertwined" (Jost 112); and in the music of Don Cherry: "Cherry's themes very often have a heterogeneous structure, that is, they consist of several parts whose motives, tonal points of reference, rhythm and sometimes tempo diverge" (Jost 142) as illustrated in a schematic diagram of the structure of Complete Communion in Figure 23. As has been previously shown, too, Stravinsky's "Symphonies of Wind Instruments" and "The Rite of Spring" similarly display such heterogeneity of themes which are directly juxtaposed and intertwined.

One last category of asymmetry in free jazz occurs in light of its textures. Collective improvisation in Mingus' music, for example, creates a group improvisation in which the part each musician plays is autonomous (note: "but not independent"!): "Nobody accompanies, nobody solos. The general mood of this music is hectic, nervous, but not chaotic" (Jost 43). Collective improvisations are similarly constructed of several autonomous lines in Coltrane's Ascension and in Coleman's Free Jazz; even though these lines are interacting and are based primarily on each other (recall: free jazz is primarily communicative, rather than composed of a group of self-absorbed individuals), there is no temporal synchronization or hierarchy between them. Such use of polyphony, or "layered texture," creates, as Jost describes above, a general mood which is disjunct in character. I have already pointed out the use of polyphony in Ligeti's "Lontano." Another example of polyphony in free jazz, however, can be found in the piano playing of Cecil Taylor, who sometimes gives equal autonomy to both hands: "Taylor's 'multi-track' harmonic language is most apparent in the melodic lines' relationship to the chords underlying them. The chords—which may be clusters hit with the left fist—do not act as a harmonic-rhythmic accompaniment to the melody as in traditional piano playing [i.e. homophony], but as an independent entity whose intensity occasionally overrides that of the upper part [i.e. polyphony]" (Jost 75). This juxtaposition of disjunct elements in Cecil Taylor's piano playing is an encapsulation, one could say, of the collective improvisation in the music of Mingus, Coleman, and Coltrane to a single instrument. Polyphony can also be found in Ligeti's "Requiem," in which even his concept of a "part," as separated in the score, is itself composed of four separate "voices."

Introduction • Main Body • Closing • References • Top

* * *The Use of Parody

Lastly, the use of parody—evoking associations with already existent material—is a common practice to free jazz and to 20th-century classical music. This "historicism," furthermore, may work to combine features of other music into new approaches rather than merely quoting them.

Several of the musicians Jost analyzes portray stylistic diversity and mix many different historical styles into their approach to free jazz. Mingus mixed elements of gospel music with the blues, European impressionism, folklore, and Duke Ellington inspired arrangements; Archie Shepp mixed the music of the present—rhythm-and-blues, and rock-and-roll—with African rhythms in some of his work; the Chicagoans mixed waltzes, Mingus, Baroque, Dixieland, swing, marches, and contemporary rock; and in Sun Ra's music there is similarly "the linkage of jazz tradition and exoticism with the advanced playing techniques of free jazz" (Jost 192). A lot of 20th-century classical music also works beyond any particular aesthetic and creates music that mixes things up. Berio's "Sinfonia" uses and manipulates Mahler, "The Rite of Spring," along with quotations from texts by Beckett and Levi-Strauss, amongst other things. Another composition of Berio's, "Laborintus 2," even combines the walking bass of jazz in a free jazz sounding context with musique concréte, people speaking French, and unorthodox sounding brass instruments. John Zorn, too, in his composition "Forbidden Fruit," incorporates many kinds of music, mixing excerpts from Bartók and Beethoven with Japanese speech, tape manipulation, record scratching, and other things, in a manner, previously noted, that could be described as a "counterpoint" of different musical styles.

A focus on Eastern and Mid-Eastern music and folksongs is also common to free jazz and to 20th-century classical music. Don Cherry, as a good example, had a "growing awareness of musical cultures of the so-called Third World, especially those of Arabia, India and Indonesia. That awareness led to the exploration of the new (old) rhythms, melodies and timbres" (Jost 148). This Eastern awareness led Cherry to play a "whole assortment of differently tuned flutes and recorders of Far Eastern origin," gongs, chimes and Balinese gamelan instruments (Jost 149). Similar influence and instrumentation can be found in Messiaen's "Turangalila Symphonie"—"Turangalila" being Sanskrit for "love song"—in which Messiaen also employs the gamelan. Cherry's interest in the Third World also led him to explore irregular meters, like those in Figure 24 below, similar to the way Messiaen was interested in using Hindu and Greek poetic meter (Messiaen chp. 2), and Bartók was interested in the asymmetrical rhythms of Bulgarian folk music (see Figure 25).

Figure 24. Jost 151 Folksongs also inspired Archie Shepp and Albert Ayler: "Albert Ayler's themes are a category of free-jazz composition all their own. Their most prominent feature is their simplicity. But unlike the music of Coleman, for example, it is not the simplicity of Black blues, but of an imaginary genre of folksongs, or folk dances..." (Jost 127); and: "Without being in any way imitative, [Shepp's compositions] contain echoes of Ellington and Mingus, overlaid on one side by the tonally disoriented sound of the Cecil Taylor groups (Into the Hot!) and on the other, by a coarse folksiness, a quality also occasionally present in later Shepp compositions" (italics added; Jost 111). Qualities of folk music are also present in 20th-century classical music as in that of Ligeti, in his use of Hungarian scales in his "Piano Concerto," and in the use of folkloric motifs in his "Violin Concerto," which employs stylized descending motifs of Hungarian music representing grief.

Introduction • Main Body • Closing • References • Top

Closing

In closing, it is important to note that most of the comparisons in this paper are made with examples from early 20th-century classical music—Bartók, Stravinsky, Debussy, early Schoenberg, Webern, and Messiaen—and not so much with reference to composers involved with later 12-tone techniques and serial music. Though extensions of tonality and conscious employments of chromaticism were well absorbed into the style of improvisation that became known as free jazz, the high degree of constructionism inherent to serial music may have proven too difficult for spontaneous expression: "The qualities and creative principles of the newest European music... are possibly too unmalleable to be integrated into the substance of jazz, without leading at the same time to a metamorphosis in which jazz itself is lost" (Jost 175).

Though I have made comparisons to more contemporary composers like John Zorn, Franco Donatoni, Luciano Berio, and György Ligeti, these composers likewise have little or no association with 12-tone music in the examples I have used. These composers have composed mostly after the time of publication of Free Jazz (1974), furthermore, and Jost's reference to the "newest European music" in the quote above implies rather the practice of serial music.

As to what developments have occurred in free jazz since 1974, that is my current pursuit of knowledge...

~end~

Introduction • Main Body • Closing • References • Top

References

- Jost, Ekkehart. Free Jazz. 1st Da Capo Press pbk. ed. 1994 (Graz, Austria: Universal Edition, 1974).

- Lester, Joel. Analytic Approaches to Twentieth-Century Music. 1st ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, c1989).

- Messiaen, Olivier. The Technique of my Musical Language. English ed. Trans. John Satterfield. (Paris: Alphonse Leduc, c1944).

©1998, john a. maurer iv